Fawzi Baalbaki is a Lebanese painter, born in 1940 in the village of Odaisseh, in the Jabal Amel region of southern Lebanon. His early years were marked by a close bond with his older brother, the...

.jpg)

.jpg)

-FawziBaalbaki-Front-(1).jpg)

-FawziBaalbaki-Front-(1).jpg)

Fawzi Baalbaki is a Lebanese painter, born in 1940 in the village of Odaisseh, in the Jabal Amel region of southern Lebanon. His early years were marked by a close bond with his older brother, the...

Fawzi Baalbaki is a Lebanese painter, born in 1940 in the village of Odaisseh, in the Jabal Amel region of southern Lebanon. His early years were marked by a close bond with his older brother, the renowned painter Abdel Hamid Baalbaki.

As children, Fawzi and Abdel Hamid crafted small artworks using limestone they collected from around the village. Using knives to carve figurines of furniture, animals, and other small forms, they learned to create through an early exploration of subtractive sculptural technique. Abdel Hamid also taught the younger Fawzi how to draw animals such as cats and swans in various styles, exposing him early on to the idea that representation was a fluid, interpretive practice. While their parents discouraged artistic pursuits, Fawzi’s schoolteacher, Adham Soueid, nurtured his talent – often displaying his drawings on classroom walls, offering him early affirmation and encouragement1.

These formative experiences, both familial and personal, set the stage for Fawzi’s formal education in art. In 1968, he enrolled at the Lebanese University’s Institute of Fine Arts, where he quickly distinguished himself, consistently ranking at the top of his class throughout his undergraduate studies. His academic success was matched by a growing curiosity about the world around him. Religion and philosophy, which he explored as a young adult, did not seem to satisfy this curiosity. It was in politics – first Baathist, then Marxist – that he found a system of thought that resonated with his interests2. During the 1960s and 70s, Marxism, with its materially grounded approach to social structures, provided a means to connect abstract ideals with lived experience. Baalbaki became actively involved in Lebanon’s vibrant leftist circles, participating in political rallies, protests, and strikes, and engaging in the spirited debates that characterized the era.3

Due to the political climate at the time, Baalbaki produced some of his early works under the pseudonym Adham al-Ameli – a name that honored both his supportive schoolteacher, Adham Soueid, and his southern Lebanese roots in Jabal Amel. Among these was an untitled 1976 painting influenced by the work of Iraqi modernist Jewad Selim4. The painting reflects Selim’s influence in its portrayal of everyday Arab life, rendered with muted tones and a naïve, non-naturalistic style. Rather than employing single-point perspective typical of Renaissance painting5, Baalbaki embraced flattened, composite spatial arrangements reminiscent of early Islamic manuscript illustration – an approach also central to Selim’s visual language.6

Not all of Baalbaki’s works from this period adopted a naïve aesthetic. He also produced more realistic depictions of everyday life, such as an untitled etching in the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF) collection. The print portrays two veiled women walking through a street framed by several qanatir – arched structures commonly found in arcaded walkways in traditional Islamic architecture.7

Baalbaki’s Arab and Islamic themed works soon gave way to new artistic explorations. In 1983, he moved to Paris, where he studied semiology – the theory of signs and systems of meaning8 – a discipline that would profoundly influence his artistic thinking. During this period, he began experimenting with what would become a signature element of his practice: his “silhouettes.” These simplified, stick-figure-like renderings of the human form emerged from his interest in symbolic representation.

Baalbaki was particularly influenced by Pablo Picasso’s use of nominal imagery – such as a bull’s head composed of abstract forms like horns and shapes that signify rather than resemble. In a similar spirit, Baalbaki’s silhouettes do not seek to depict individuals, but rather to suggest presence, movement, and human relation through minimal line and gesture. The first ideas for these figures came to him at Café de l’Éscholier, and he began developing them seriously during his time in Paris. French critics responded positively, praising the artist’s execution.

In 1987, Baalbaki returned to Beirut from Paris9, continuing to develop his abstracted silhouettes alongside other experimental works. In 1993, he completed a painting titled Laylat al-Qadr10, named after the Islamic night commemorating the first revelation of the Qur’an to the Prophet Muhammad. The composition features a thin, minimally rendered human figure standing among a grove of anthropomorphic trees, their branches echoing the figure’s elongated limbs. Small birds appear throughout the abstracted landscape – roaming the undulating hills or perched beside a net suspended from one of the tree-forms – adding to the painting’s quiet symbolism and contemplative tone.

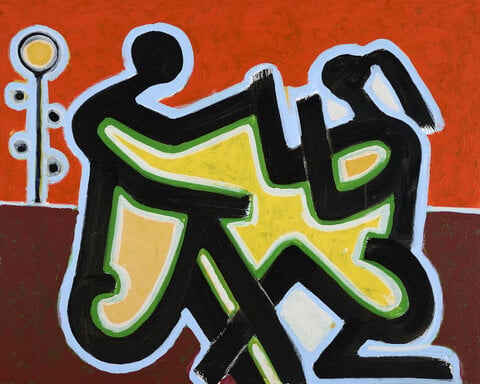

From the 2010s onward, Baalbaki’s compositions began to forgo deep spatial backgrounds in favor of flat fields of color11. He created a series of acrylic paintings on canvas and wood, featuring his signature stick-like silhouettes set against bold monochromatic or duochromatic backgrounds12. These figures often appear contorted, gesturing, or folding into one another, evoking a sense of ritual, intimacy, or communal choreography. Many of these works also include cats or sleeping domestic animals nestled beside the human forms – visual echoes of the birds featured in Laylat al-Qadr, 1993, reinforcing themes of presence, stillness, and quiet observation.

In The Dancers Series 1, 2024, also part of the DAF collection, a group of gesticulating silhouettes is linked together and surrounded by a shared blue glow, creating a visual field charged with movement and connection. Other works from 2024 and 2025 in the foundation’s collection depict the space between two figures illuminated with color and geometric form, embodying the very proximity and intimacy between the two figures.

Baalbaki’s approach to form is not driven by geometry or academic composition, but by what he calls “lines of power.” These intuitive imagined lines help him find the most consistent or intuitively apparent way for the subject matter to appear.

Fawzi Baalbaki is part of a remarkable artistic lineage. His brother Abdel Hamid, his sons Said and Ayman Baalbaki, as well as relative Oussama Baalbaki, have each made significant contributions to Lebanese and Arab artistic canons. Together, they form a multigenerational family of painters whose practices, both figurative and abstract, engage with themes of history, memory, identity, and the lived experiences of Arab communities.

Today, Baalbaki lives and works in Beirut, where he continues to develop his visual language through painting and collaboration. While his work has recently been featured in the group exhibition Pourquoi Il Fait Si Sombre?, 2025, at DAF Beirut, his practice remains above all a personal exploration, rooted in intuition, shaped by decades of reflection, and sustained by a quiet yet persistent search for meaning through form.

Edited by Elsie Labban

[1] Chadi Hazime, Fawzi Baalbaki: L’Hymne de l’Art (2025), film.

[2] “خوابي الكلام - فوزي بعلبكي,” YouTube video, July 11, 2019, 54:11, posted by Tele Liban, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoF2oFP7JBs&t=2401s.

[3] Interview with Fawzi Baalbaki, video recording, courtesy of the Ramzi and Saeeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

[4] “Pourquoi Il Fait Si Sombre? Ayman Baalbaki | DAF Beirut,” YouTube video, March 20, 2025, 12:49, posted by Dalloul Art Foundation, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UjF1fSdFPc.

[5] The College Board, “The Development of One-Point Perspective in Renaissance Italy,” AP Central, accessed June 25, 2025, https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-art-history/classroom-resources/development-one-point-perspective-renaissance-italy.

[6] Amin Alsaden, “To See an Eclipse: Crescents in Jewad Selim’s Baghdadi Modernism,” Smarthistory, August 2024, accessed June 25, 2025, https://smarthistory.org/jewad-selim-young-man-and-wife/.

[7] “Qanatir (Scale Arches),” Madain Project, 2022, accessed June 25, 2025, https://madainproject.com/qanatir_(scale_arches)

[8] “Semiology,” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, accessed June 25, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/semiology.

[9] Interview with Said and Ayman Baalbaki, by Liam Sibai, June 25, 2025, as part of the Ramzi and Saeeda Dalloul Art Foundation

[10] Adam Zeidan, “Laylat al-Qadr,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed June 25, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Laylat-al-Qadr.

[11] Fawzi Baalbaki, Untitled (1992), courtesy of the artist.

[12] Fawzi Baalbaki, Laylat Al-Qadr (1993), courtesy of the artist.

Sources

Alsaden, Amin. “To See an Eclipse: Crescents in Jewad Selim’s Baghdadi Modernism.” Smarthistory, August 2024. Accessed June 25, 2025. https://smarthistory.org/jewad-selim-young-man-and-wife/.

Baalbaki, Fawzi. Laylat Al Qadr. 1993. Courtesy of the artist.

Untitled. 1992. Courtesy of the artist.

Chadi Hazime. Fawzi Baalbaki: L’Hymne de l’Art. 2025. Film.

College Board. “The Development of One-Point Perspective in Renaissance Italy.” AP Central. Accessed June 25, 2025. https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-art-history/classroom-resources/development-one-point-perspective-renaissance-italy.

Dalloul Art Foundation. “Pourquoi Il Fait Si Sombre? Ayman Baalbaki | DAF Beirut.” YouTube video, 12:49. Posted March 20, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UjF1fSdFPc.

Interview with Fawzi Baalbaki. Video recording. Courtesy of the Ramzi and Saeeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

Interview with Said and Ayman Baalbaki. By Liam Sibai. June 25, 2025. As part of the Ramzi and Saeeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

Madain Project. “Qanatir (Scale Arches).” 2022. Accessed June 25, 2025. https://madainproject.com/qanatir_(scale_arches).

Merriam-Webster. “Semiology.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Accessed June 25, 2025. https://www.merriam-webster.co... Liban. “خوابي الكلام - فوزي بعلبكي.” YouTube video, 54:11. Posted July 11, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoF2oFP7JBs&t=2401s.

Zeidan, Adam. “Laylat al Qadr.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed June 25, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Laylat-al-Qadr.

Selected Solo Exhibitions

The Escape to Joy, Dalloul Artist Collective, Beirut, Lebanon

Solo Exhibitions, Beirut, Lebanon

Selected Group Exhibition

Prints & Printmaking, Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

Possible Group or Solo Exhibitions in Paris, France

Collections

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-FawziBaalbaki-Front.jpg)

-FawziBaalbaki-Front.jpg)