Born in 1919, in the village of Kafr Mansour, a governorate of Beni Soueif, Egypt, Hamed Owais grew up amongst a family of peasants, and later emerged as a progressive artist[i]. Considered one of...

Born in 1919, in the village of Kafr Mansour, a governorate of Beni Soueif, Egypt, Hamed Owais grew up amongst a family of peasants, and later emerged as a progressive artist[i]. Considered one of...

Born in 1919, in the village of Kafr Mansour, a governorate of Beni Soueif, Egypt, Hamed Owais grew up amongst a family of peasants, and later emerged as a progressive artist[i]. Considered one of the leading Social Realist painters in Egypt, Owais’ work embodies the struggle of the people of the Egyptian working class. Following his secondary school education, Owais worked as a metalworker, then he pursued his college studies, graduating from the School of Fine Arts in Cairo, in 1944. He continued his studies receiving another diploma from the Cairo Institute of Art Education in 1946, after being trained by his drawing teacher, and pedagogue, Youssef el-Afifi. In the following year, Owais co-founded the Group of Modern Art, together with other artists of his generation, including Gamal el-Sigini, Gazbia Sirry, Zeinab Abdel Hamid, Salah Yousri, and Youssef Sida[ii].

Between 1948 and 1955, Owais served as a drawing instructor at the Farouk First Secondary School in Alexandria[iii]. The bright light and colorful landscape offered by the Mediterranean city, inspired Owais, who was also influenced by his mentor, master colorist Mahmoud Saïd (1897-1964)[iv]. In 1958, Owais was appointed professor at the newly created Faculty of Fine Arts in Alexandria, for which he later headed from 1977 to 1979. However, during 1967 to 1969, Owais took a break from teaching; he traveled to Madrid where he continued his studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando[v].

As an Egyptian artist with a formal education focused on modern European art[vi], Owais drew inspiration from the abstract art masters like Picasso and Matisse. Moreover, he was influenced by the Fauvist movement where artists adopted artificial colors in rendering figurative paintings. Most notably, Owais’ art practice resonated with Mexican Social Realists, such as Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros[vii]. The works of such artists called attention to the declining conditions of the poor and working classes, and challenged social systems that lead to such conditions.

Scenes of everyday life in Egypt were central to Owais’ themes. They were evident in his works throughout his career. According to Liliane Karnouk, visual artist and former professor at the American University in Cairo, Owais’ artistic production in the late 1940s reflected a strong temperament, namely in his use of bold colors. However, it was a period of exploring and experimenting different techniques[viii]. In one of his early paintings titled Alexandria tram station, 1950,[ix] Owais depicts the busy urban life in Cairo. With vivid and warm colors, he paints cars, pedestrians, trains, and bicycles with intertwined trajectories.

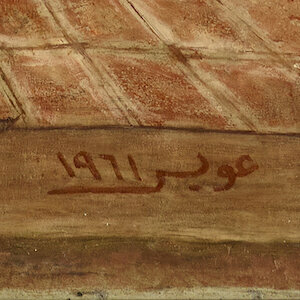

In the early 1950s, when revolutionary ideas were fermenting, Owais developed a visual language inspired by anti-fascist Italian painters whose works he encountered during his visit to the 1952 Venice Biennale[x]. Owais’ artistic voice was consolidated in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, which culminated in the ascent of Gamal Abdel Nasser. On July 26, 1956, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal[xi], ending British occupation since 1882 and French influence from 1798[xii], marking a pivotal moment in Egypt's modern history and inspiring decolonial revolutions across Africa and Asia[xiii].

The political and social climate of the region at the time impacted Owais’ work reflecting as Social Realism, where he addressed daily life subject matters legible to the common people, and hence targeted a wider public. He portrayed heroic figures and anonymous everyday workers who symbolize persistence and strength in the face of adversity. For instance, the optimism of the Nasser era (1956-1970)[xiv] and the strengthened collectivism of the time is clearly represented in Owais’ painting Nasser and the nationalization of the canal, 1957[xv], which portrays Nasser against the backdrop of the Suez Canal holding a public speech. The power of the anti-colonial revolution is communicated here through the over-sized figure of President Nasser. Nasser’s body occupies almost the full canvas. Thus, he is made a symbol of the decolonial revolution. Furthermore, by depicting in detail the faces of the people that constitute the tight crowd surrounding the president, Owais humanizes the masses. In doing so he asserts the importance of the people in the achievement of socio-political goals. The artwork serves as a powerful symbol of national pride and defiance against foreign domination, encapsulating the spirit of the Egyptian people's struggle for sovereignty.

Owais and the other artists of the Modern Art Group gained momentum in the early 1950s, as the political changes in the country influenced their conceptualization of the role of art.[xvi]. They believed that revolutionary ideology should be communicated to people through art. Consequently, they rejected Surrealism because it was perceived as a conceptual and rebellious art which did not resonate with the larger population. The Modern Art Group promoted an art that aimed to break out from the elite cultural circle in order to reach all societal levels. Hence, establishing an Egyptian identity involved engaging with established social frameworks, such as labor and the livelihood of peasants[xvii]. Owais showed a long-term engagement in producing snapshots of rural life that celebrated the everyday worker as a hero.

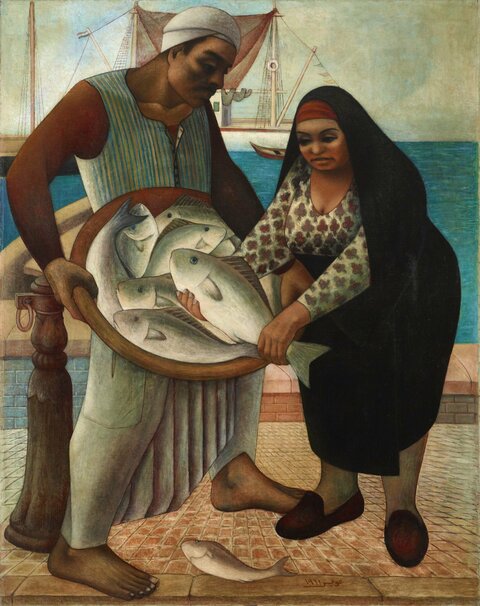

In the painting People and fish, 1961 – currently part of the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation collection – a man and a woman display the fruits of their labor, presumably along the banks of the Nile River. The man stands barefoot, holding a basket of fish. His volumetric arms are bent with the elbows pointing away from his body, recalling physical strength, while the strong contrast of light on his face suggests prolonged exposure to sunlight. The woman leans forward, holding one of the fish from the basket with both hands and straight arms. Positioned precisely at the center of the canvas, the held fish becomes the focal point of the composition. Additionally, the angle of the basket, almost losing its three-dimensional quality and appearing almost two-dimensional, underscores the deliberate display of its contents. Moreover, the outline of the tilted basket seems to extend to the man's right arm and the woman's left arm, creating a circular composition that is completed by the bowed heads of the figures. This particular assemblage translates the symbiotic relationship between the Egyptian people and the Nile, emphasizing the vital role that the river plays in sustaining life and livelihoods. With its focus on the fruits of labor, the painting appears to promote overcoming feelings of inferiority and underscores the significance of rural laborers in society.

Owais´ artistic aspiration was greatly supported by the Egyptian state. Art graduates were employed in the new government initiatives in the fields of education, publishing, and culture. Sponsorships and grants were given to artists who supported and documented the modernization of the country[xviii]. Like many artists of his time, Owais depicted the construction of the Aswan High Dam that started in 1960. The objective of the High Dam was to safeguard Egypt’s ability to meet its own needs by creating a massive reservoir, called Lake Nasser, through the containment of the Nile River. This reservoir would be utilized to convert the river’s flow into hydroelectric power, thereby bolstering the independence of the newly established nation[xix].

Owais' portrayal of the dam can be interpreted as propaganda, as it celebrates the achievements of the state; however, it also sheds light on the significant role of workers in realizing national projects. In The hall of the machine, 1964[xx], four workers are depicted participating in the construction of the electric towers adjacent to the dam's power station. Although the workers' faces are obscured either by helmets or by the tools and metal structure they are working on, their arms and hands are clearly visible as they engage in screwing and welding tasks. By mimicking the mechanical movements of the machine, the workers become integral parts of the very mechanism they are constructing. Consequently, the labor of these workers is portrayed as indispensable for the existence of the electric towers.

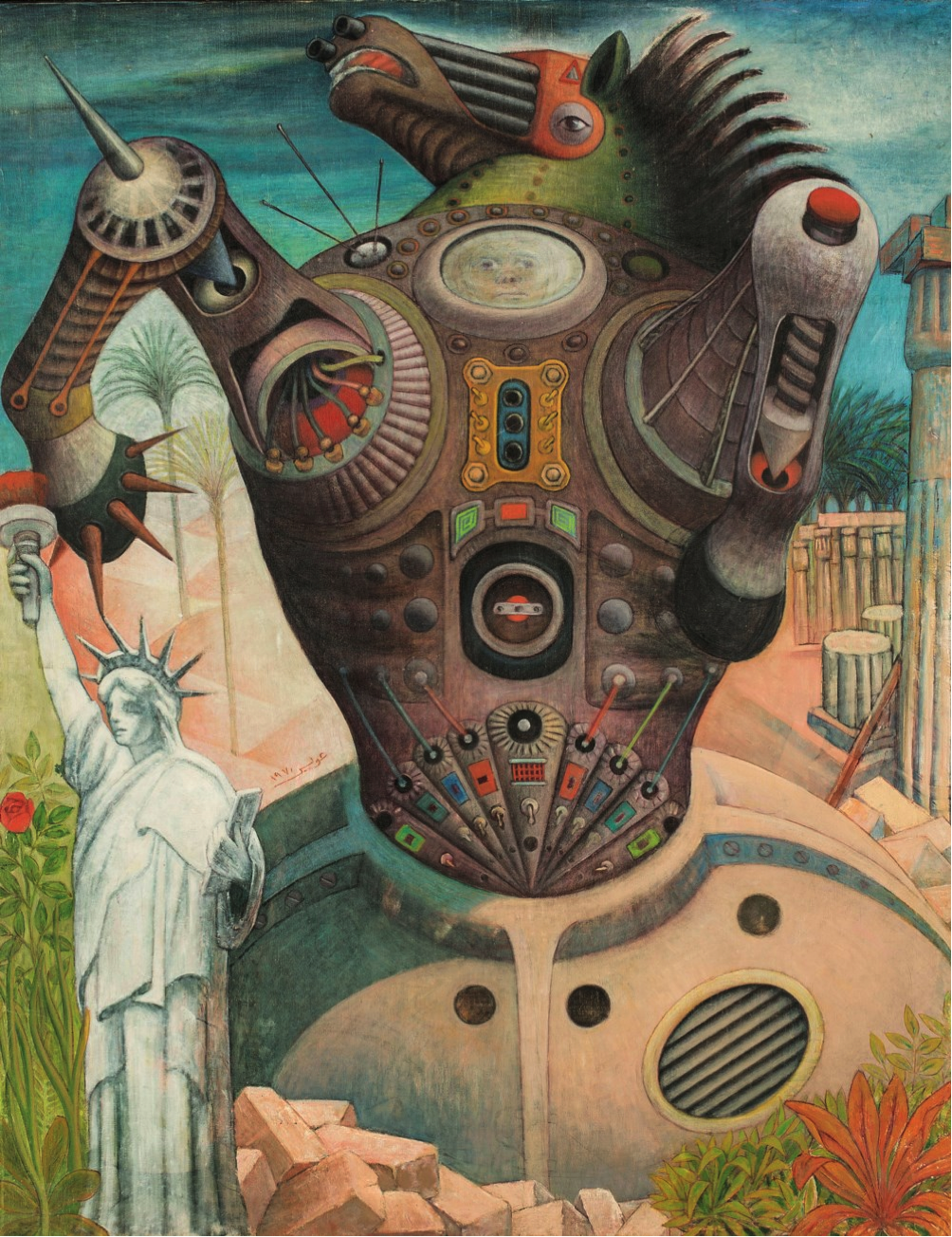

In the aftermath of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, during which Egypt lost the territory of the Sinai Peninsula to Israel, Owais persisted in showing a profound national pride by visually celebrating the Egyptian military and the country's technological advancements. However, in his works addressing the conflicts between Egypt and Israel, Owais appeared to adopt an aesthetic reminiscent of Surrealism, from which he had previously distanced himself as a member of the Modern Art Group. For example, in America, 1970[xxi], the main figure is a towering mechanical warhorse, potentially symbolizing the might of the Egyptian military, and about to demolish a much smaller Statue of Liberty, serving as a symbol of America, Israel’s ally. Additionally, the color palette diverges from the earthy, subdued tones previously employed for his rural laborer subjects, instead opting for bold and contrasting colors such as blue and orange, recalling the aesthetic associated with the Spanish Surrealist Salvador Dalí. Owais' In America not only reflects a continued effort to evoke a Pan-Arab sentiment but also conveys a hope for eventual national triumph over foreign invasion.

Owais' work is a testament to the enduring spirit of Egyptian pride and resilience. His art, marked by a fusion of realism and symbolism, vividly portrays the everyday lives of the working class, celebrating their existence and contributions. Owais' commitment to depicting the socio-political landscape of Egypt, from the revolution of 1952 to the Arab-Israeli war of 1967, reflects his deep connection to his nation's aspirations for sovereignty and progress. He passed away in Cairo in 2011, at the age of ninety-two.

Edited by Wafa Roz & Elsie Labban

References:

Centore, Kristina. “Future Tense: Hamed Owais and Aswan High Dam.” SEQUITUR (July 2020). Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture

Christie´s. “Hamed Ewais (Egyptian, 1919-2011), America.” Accessed March 10, 2024. www.christies.com/lot/

Karnouk,Liliane. Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. “President Gamal Abdel-Nasser.” Accessed April 30, 2024. https://jfk.artifacts.archives.gov/people/537/president-gamal-abdelnasser

Mileeva, Maria. “Imagined Solidarities: Cairo-Moscow and the Struggle for Realist Art.” Art History 45, no. 5 (November 2022): 974–995

Mutual Art. “Hamed Owais: Al Zaim w Ta'mim Al Canal (Nasser and the Nationalisation of the Canal), 1957.” Accessed March 2, 2024. https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Al-Zaim-w-Ta-mim-Al-Canal--Nasser-and-th/EBA006F1494BAFB2

Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute United States Department of State. “The Suez Crisis, 1956.” Accessed March 2, 2024. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/suez

Radwan, Nadia. “Hamed Owais.” Mathaf encyclopaedia of modern art and the Arab world. Accessed March 1, 2024

Zamalek Art Gallery. “Alexandria Tram Station, 1950.” Facebook, December 25, 2010. https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=180790758606193&set=a.180790621939540.42253.179700888715180

Alexandria tram station, 1950

Nasser and the nationalization of the canal, 1957

The hall of the machine, 1964

America,

1970

The hall of the machine, 1964

America, 1970

Edited by Wafa Roz & Elsie Labban

Notes:

[i] Maria Mileeva, “Imagined Solidarities: Cairo-Moscow and the Struggle for Realist Art,” Art History 45, no. 5 (November 2022): 974–995

[ii] Nadia Radwan, “Hamed Owais” Mathaf encyclopaedia of modern art and the Arab world, accessed March 1, 2024

[iii] Nadia Radwan, “Hamed Owais” Mathaf encyclopaedia of modern art and the Arab world, accessed March 1, 2024

[iv] Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003 (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005), 80

[v] Nadia Radwan, “Hamed Owais” Mathaf encyclopaedia of modern art and the Arab world, accessed March 1, 2024

[vi] Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003 (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005), 78-79

[vii] Nadia Radwan, “Hamed Owais” Mathaf encyclopaedia of modern art and the Arab world, accessed March 1, 2024

[viii] Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003 (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005)

[ix] Zamalek Art Gallery, “Alexandria Tram Station, 1950,” Facebook, December 25, 2010, www.facebook.com/photo/

[x] Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003 (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005), 78-79

[xi] “The Suez Crisis, 1956," Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute

United States Department of State, accessed March 2, 2024, www.history.state.gov/milestones

[xii] Kristina Centore, “Future Tense: Hamed Owais and Aswan High Dam,” SEQUITUR (July 2020), Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture

[xiii] Kristina Centore, “Future Tense: Hamed Owais and Aswan High Dam,” SEQUITUR (July 2020), Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture

[xiv] “President Gamal Abdel-Nasser,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, accessed April 30, 2024, www.jfk.artifacts.archives.gov

[xv] “Hamed Owais: Al Zaim w Ta'mim Al Canal (Nasser and the Nationalisation of the Canal), 1957,” Mutual Art, Accessed March 2, 2024, www.mutualart.com

[xvi] Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003 (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005), 77

[xvii] Liliane Karnouk, “Interview with Owais, Spring 1984,” In Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003, (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005), 80

[xviii] Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art 1910-2003 (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005), 67

[xix] Kristina Centore, “Future Tense: Hamed Owais and Aswan High Dam,” SEQUITUR (July 2020), Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture

[xx] Maria Mileeva, “Imagined Solidarities: Cairo-Moscow and the Struggle for Realist Art,” Art History 45, no. 5 (November 2022): 974–995

[xxi] “Hamed Ewais (Egyptian, 1919-2011), America,” Christie´s, accessed March 10, 2024, www.christies.com/lot

Selected Group Exhibitions

Crossroads: A Collector’s Tale, Picasso Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

Selection, Zamalek Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

Modern Art from the Middle East, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, USA

Mathaf Collection, Summary, Part 2, MATHAF, Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

Barjeel Art Foundation Collection Imperfect Chronology – Debating Modernism I, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, UK

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies