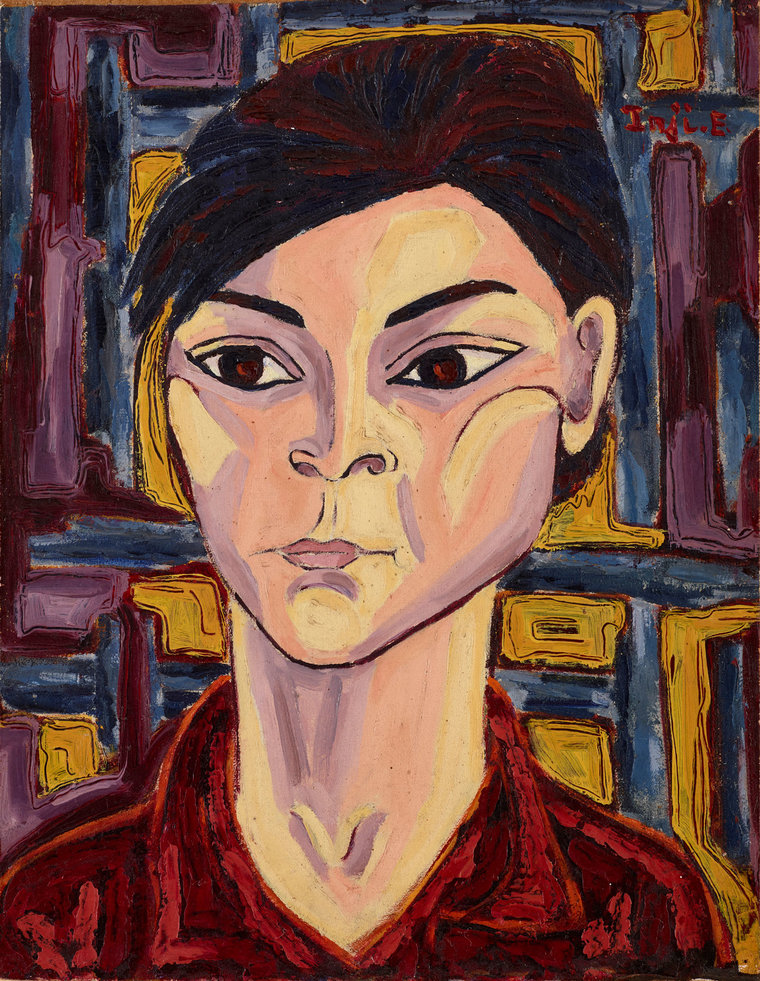

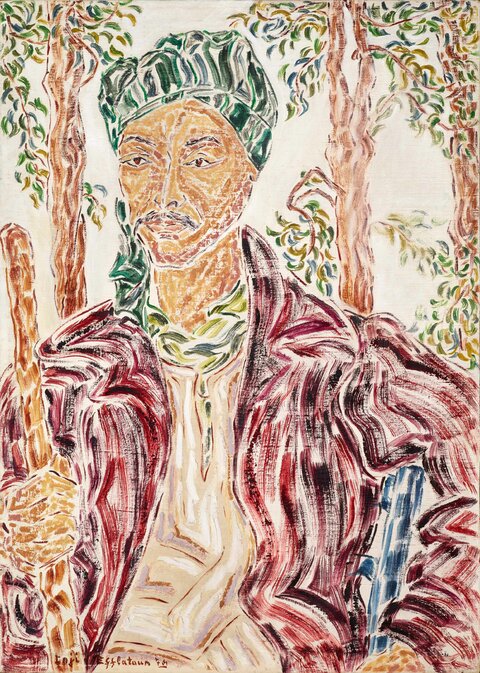

Portrait of a Girl, 1950s, is a self-portrait by the Egyptian artist Inji Efflatoun. The facial features are static and severe as the woman looks away from the viewer. While no clear emotion is evident, the artist accentuated some of the features such as the jawline, the eyebrow arches, the cheekbones, and the nose bridge – which together give the impression of strength. The woman’s pursed lips and gaze looking away suggest that she is an observer, looking upon something outside of the frame. The background, with its movement through evident brushstrokes and sharp contrasts, brings in some of the colors from the forefront, and creates a dynamic energy that pushes the subject of the painting forward.

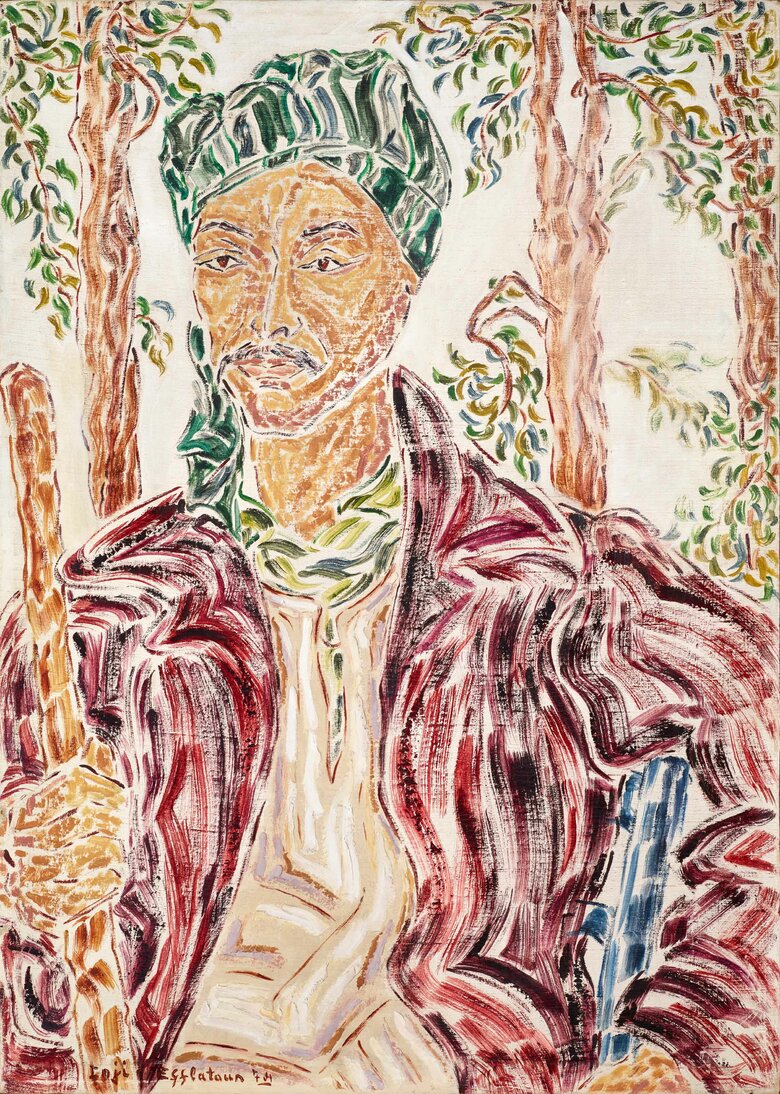

This self-portrait offers a glimpse at how Efflatoun perceived herself: this is not the image of a passive individual as much as it is of someone studying and observing the surroundings, about to take action. Behind the deep, focused gaze is the determination of “a national hero, a feminist icon and one of the most important figures in the history of modern Egyptian art.” Efflatoun’s political activism, especially in relation to feminist issues, extends to her artworks in relation to the ways in which she chooses to depict women. This portrait carries similar elements to the portraits of prisoners series that Efflatoun painted during her imprisonment between 1959 and 1963: like the self-portrait here, the women were painted from the bust up, their faces at the center with the light and shadow brightly reflected, and the background often depicted as a grid to reflect the prison bars. These elements show the influence of the social realist style of Mexican muralist David Alfaro Sequieros (they became acquainted in 1957), whose works follow similar themes of political activism as well as dramatic effects of light and shadow.

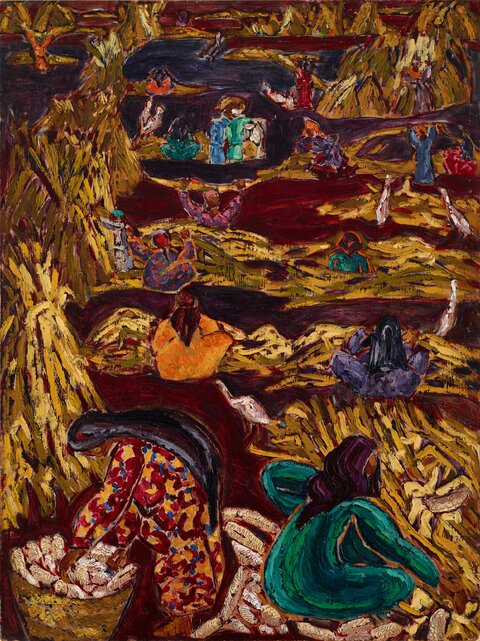

Efflatoun’s artistic style saw several significant shifts throughout her life that were intimately linked to her personal and political growth, especially her personal relationship to her own aristocratic background. From a young age, Efflatoun had felt distanced from the aristocratic class that surrounded her. It was during her schooling at the Lycée Français that she got to meet and engage with other young women of various social and economic backgrounds. It proved to be a pivotal experience that shaped Efflatoun’s perception of the class divide, pushing her to question the status quo. Later, Efflatoun refused to go to Paris to study drawing, as her mother wanted, and instead began working as a drawing teacher at her old school in order to become financially independent from her family. However, she found it difficult to bridge the gap between her background and the underprivileged classes she often portrayed and championed: “In truth I could never rid myself of this complex, the complex of guilt for being both a rich girl and a socialist.”

For several years, between 1946 and 1948, she did not paint, and instead focused her efforts on women rights issues, writing, publishing, and travelling across Egypt to the poorest areas. These trips allowed her to get in touch with her Egyptian heritage and she began painting again. It was also during this time that she met her husband, leftist lawyer Mohammed Abdul Elija, who helped her overcome her shame regarding her privilege through his support and encouragement. She would regain her artistic drive as her works focused on the political upheavals of the time, with her first solo exhibit in 1952 reflecting the anti-colonial struggle of the nation against the British. In 1957, her husband was arrested and then died of a brain hemorrhage, most likely from beatings in jail. Efflatoun became more vocal about her politics, even going undercover as a peasant for a period of time, until she was caught and jailed in 1959 for her activism.

Signed and dated in English on the upper left front.