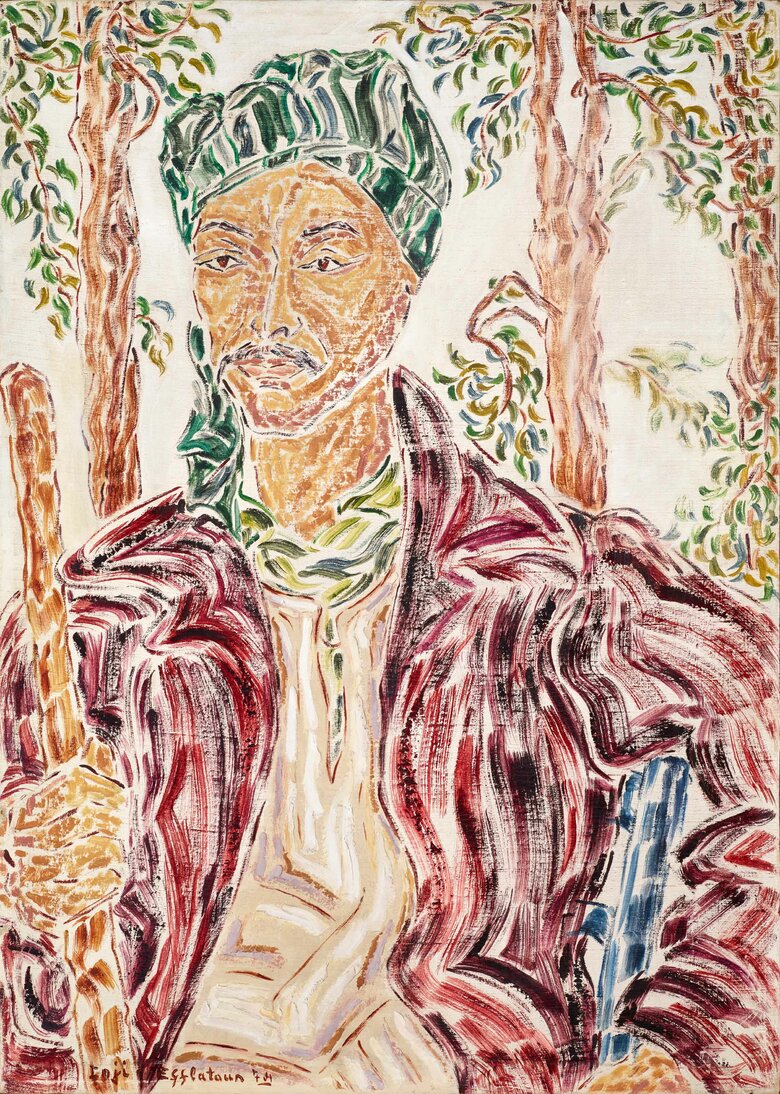

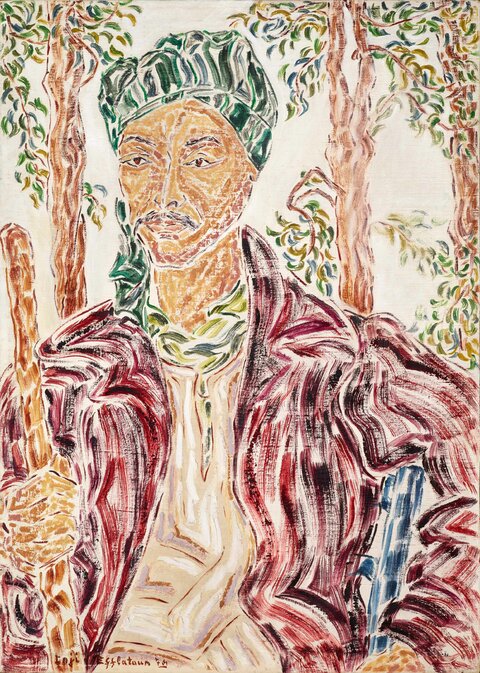

Portrait of a Prisoner, 1963, also known as "Ahlam al-sitt Bahanna", is a powerful depiction of a woman in confinement, painted during Inji Efflatoun’s own over four-year imprisonment. This work was painted while Efflatoun was imprisoned in 1959 by the Gemal Abdel Nasser government for her affiliation with the Communist Party during a period of political repression in Egypt, marking her as one of Egypt’s first female political prisoners. During her four-and-a-half years of incarceration, she experienced the harsh realities of prison life and connected with the working class more than ever before, painting portraits of thieves, murderers, and sex workers whom she shared living quarters with.

The way in which Efflatoun painted the prisoner is meant to humanize her. In thick, interrupted short brush strokes and complementary colors of ochre and deep blue toned down with bold browns, the prisoner’s portrait occupies much of the painting's rectangular composition. Dressed in a lilac headscarf and a striped prison uniform, she is illuminated by a halo of golden light. The face is painted in careful degradations of yellow and brown; the downcast eyes and amplified use of light and shadow convey a sense of anguish in the woman’s face. She looks down at her hands that are sewing a cloth for a child she hopes to conceive. The title, "Ahlam al-sitt Bahanna," meaning "The dreams of Lady Bahanna," in Arabic, underscores the woman’s longing for a child, perhaps represented by the small figure reminiscent of an Egyptian folk doll which appears over her shoulder. Her act of embroidering a garment for a future child serves as a testament to resilience and commemorates the women prisoners, including Efflatoun, who won the right to engage in manual labor after protesting through a hunger strike

Efflatoun aimed to document the "misery of women in our society," emphasizing her commitment to representing the struggles of working women. Despite the grim conditions, Efflatoun viewed her imprisonment as a sign of progress toward gender equality and a testament to women's political power, illustrating that women posed a threat to the authorities. In prison, she reflected, “I became more open to people, to life. Before I didn’t compromise. Now if I see someone’s weakness, I accept it.” This transformative period, and the paintings she did, such as Portrait of a Prisoner, deepened her understanding of women’s social struggles and human resilience.

Signed and dated in English on the upper left front.