As of the 1950s, the big challenge for the formerly colonized countries was to build a nation-state. The latter political concept refers to a nation whose population shares the same history, language, and culture. When he acceded to the throne in 1961, King Hassan II (1929-1999) faced this particular challenge. He had to consolidate the borders of the kingdom, and reinforce the nationalist sentiment among his subjects. More specifically, the monarch aimed to constrain any potential internal conflicts between the multiple ethnical groups living in the country. As a matter of fact, Morocco has always been the land where various ethnicities cohabited, including Arabs, Sephardic Jews, Sub-Saharan Africans, and certainly Berbers. Needless to say, these ethnicities have always had their own cultures, customs, languages, and even sometimes beliefs.

Hence, in the establishment of a nation-state, how could such diversity contribute to the foundation of one unique national culture? The modern art movement in Morocco emerged from this historical context. Ending years of management by French directors, Farid Belkahia (1934-2014) was the first native Moroccan artist to head the Casablanca Art School in 19611. He gathered a pedagogical team, especially with the artists-teachers Mohammed Chebaa (1935-2013) and Mohamed Melehi (1936-2020), with whom he would form the Casablanca Art Group2. Some other artists like Mohammed Hamidi (1941-), Mohamed Romain Atallah (1939-2014), and Mustapha Hafid (1942-) also joined the group. Their vision actually shaped the avant-garde movement from an artistic, cultural, and intellectual perspective in Morocco. They all participated in the process of Moroccanization of the disciplines in the Casablanca Art School.

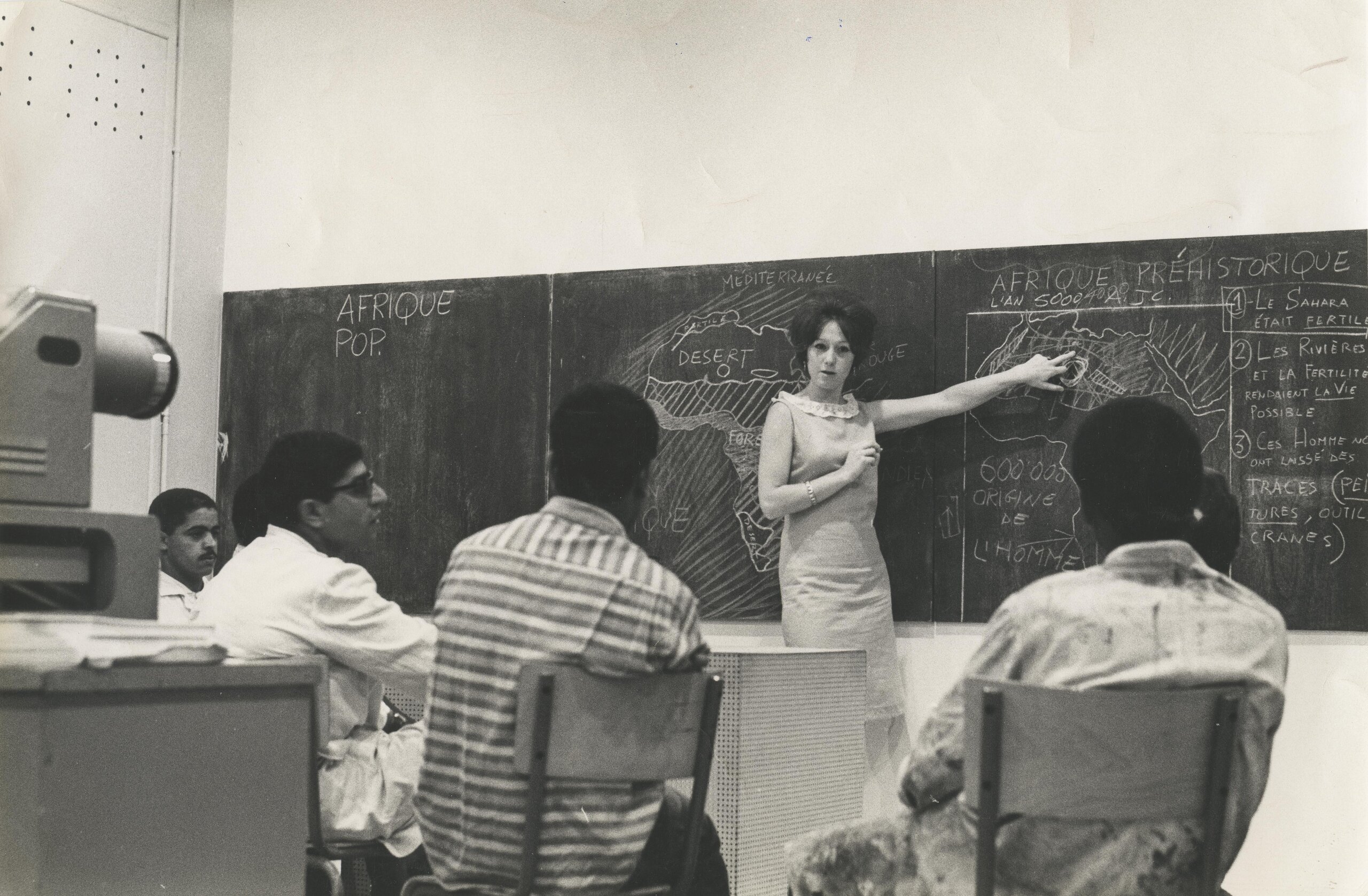

As the teaching was detaching itself from a European academic model, the teachers wanted the students to be innovative in their training and creation. Yet, this process had to go along with considering Moroccan identity. The students were taught to reconnect with the heritage from their own past (fig.1). After 44 years of French protectorate (1912-1956), it was effectively essential to educate the new generation about what defines the culture in Morocco through the study of traditional craftmanship for instance.

Figure 1 Toni Maraini teaching Art History at the École des Beaux-Arts

in Casablanca, c.1965.Photo: M.Melehi. Toni Maraini Archives.

Knowing about the local roots was necessary to create a modernity specific to the Moroccan people. Mohammed Melehi envisioned: “J’ai découvert ensuite que l’on ne pouvait pas importer le modernisme. La réhabilitation de nos propres valeurs était une action autrement plus vitale et urgente"3. They would conceive the development of the national culture as the effort of a whole community.

The Art for a Social Revolution

The year 1961 at the Casablanca Art School symbolically marked the end of an era, when the early 20th century European modern expansion was vividly questioned4. Farid Belkahia (1934-2014) brought a revolutionary vision to the teaching of fine arts. It was readapted according to the social reality in Morocco. The artists-teachers in the Casablanca Art School pushed their common duty beyond the educational sphere. In fact, they believed that modern Moroccan art could resolve the cultural and social issues which were ongoing at the time5.

Art and culture had to be integrated into the daily landscape of Moroccans. Thus, there was a clear intention to separate from a colonial conception of the art and conditioning. Artist and architecture instructor Mohamed Chebaa (1935-2013) regretfully commented on the situation in which the Moroccan people were left in after the independence of the country in 1956: “Our society’s taste has been corrupted. Consequently, we are obliged to start from scratch. Without this corruption, we could have started from a given (tradition). This work of depersonalization and corruption brought about by colonialism continues today because the masses are denied the right to education and culture”6.

The Casablanca Art Group wanted the people to see, contemplate, appreciate, or simply react to artistic production. The art was not conceived to be exclusively made for upper and educated social classes anymore. It had to be part of the collective memory. The most remembered project that the artists organized to bring art to people was the manifesto-exhibition called ‘Présence Plastique’. The event took place in Jama’a El Fnaa square in Marrakesh on May 9th, 1969 (fig.2), and then, on the Place du 16 Novembre in Casablanca in June of that same year (fig.2). For the occasion, the artists and their students presented their artworks outdoors. Almost a decade later, Mohamed Melehi (1936-2020) launched the first edition of the Cultural Musim in Asilah in 1978. The festival was initially conceived to clean and restore the streets in the coastal city in North Morocco, alongside the public programs and the creation of murals by several artists.

Figure 2 Présence Plastique, manifesto-exhibition, Place du 16 Novembre,

June 1969, Casablanca. Photograph : Mohamed Melehi. Mohamed Melehi

archives: Toni Maraini, Faten Safieddine. Mohamed Melehi Estate.

Through all these initiatives, every passerby was encompassed with art surrounding them. The Casablanca Art Group transformed, and even revolutionized, the artistic practice. They even changed the way art in Morocco was being understood. The art practice became a means for visual education and was mainly dedicated to the community. Optimizing public space with art pieces strongly detached the art practice from the – colonial – institutional system, which had imprisoned it within the walls of a school or a museum. The movement appeared as a new cultural national phenomenon, which included the material culture of Moroccan people.

Enhancing Artisanal Production

The teachers at the Casablanca Art School all taught students by following one common directive: promoting the local artistic patrimony. Since the beginning of the 1960s, a renewed interest in traditional Moroccan artisanat was manifested in the artworks. Toni Maraini (1941-) asserted: “Superficially treated as ‘decorative’ (…) this art [the popular art production], on the contrary, is as meaningful and communicative as others”7. The latter popular art production had always been considered to be secondary in comparison to art. However, the value of popular art had to be reconsidered since it genuinely belonged to the savoir-faire of the Moroccan people – usually of certain ethnicities – having been transmitted through generations.

By extension, reviving the artisanal production required its study. The search for a deep-rooted culture was fundamental to the curriculum at the Casablanca Art School. Hired as a teacher of History of Art, Dutch anthropologist Bert Flint (1931-) constituted a significant collection of folk Tran-Saharan arts and crafts. Amongst many objects, the collection encompassed rugs – like the Zemmour carpet preserved at the Tiskiwin Museum in Marrakech (fig.3) – and jewelry, to which he gave his students access. In parallel, Flint went on several trips between 1965 and 1967. He travelled from the eastern High Atlas to the Niger River, where he discovered the Berber peoples and their way of life.

On another note, it is worth highlighting that the approach used by teachers and artists at the Casablanca Art School was almost anthropologic. They were all particularly attentive to the artisanal production of the Berber people (Chleuhs, Zayanes, Rifians), who were known to be the most ancient inhabitants in North Africa before the 5th century8. The work on colors, forms, signs, and even materials fascinated the members of the Casablanca Art Group. Here, the symbolism is also relevant as the culture of an ethnic group is actually taken into consideration in a national cultural movement9.

Figure 3 A Zemmour carpet. Khémisset region, Morocco.

Bert Flint Collection, Tiskiwin Museum, Marrakech.

Photo: Alice Dufour-Feronce.

Rapidly, the popular material culture became a source of intellectual reflection in the 1960s and 1970s. Sociologists, artists, and poets presented their analyses in many magazines. Some were published in Souffles from 1966 to 1971, and Intégral, published between 1971 and 1978. The reflections and discussions fostered the idea that a link can be made between the traditional artisanat (jewelry, pottery, tapestry) and modern artistic concepts. The artistic production by the Casablanca Art Group resulted from this connection. It actually followed a historical logic, though with a new perception brought by the artists.

The Tradition for a Modern Future

‘Le statut de l’art traditionnel au Maroc est futuriste’10

Mohammed Chebaa, 1967

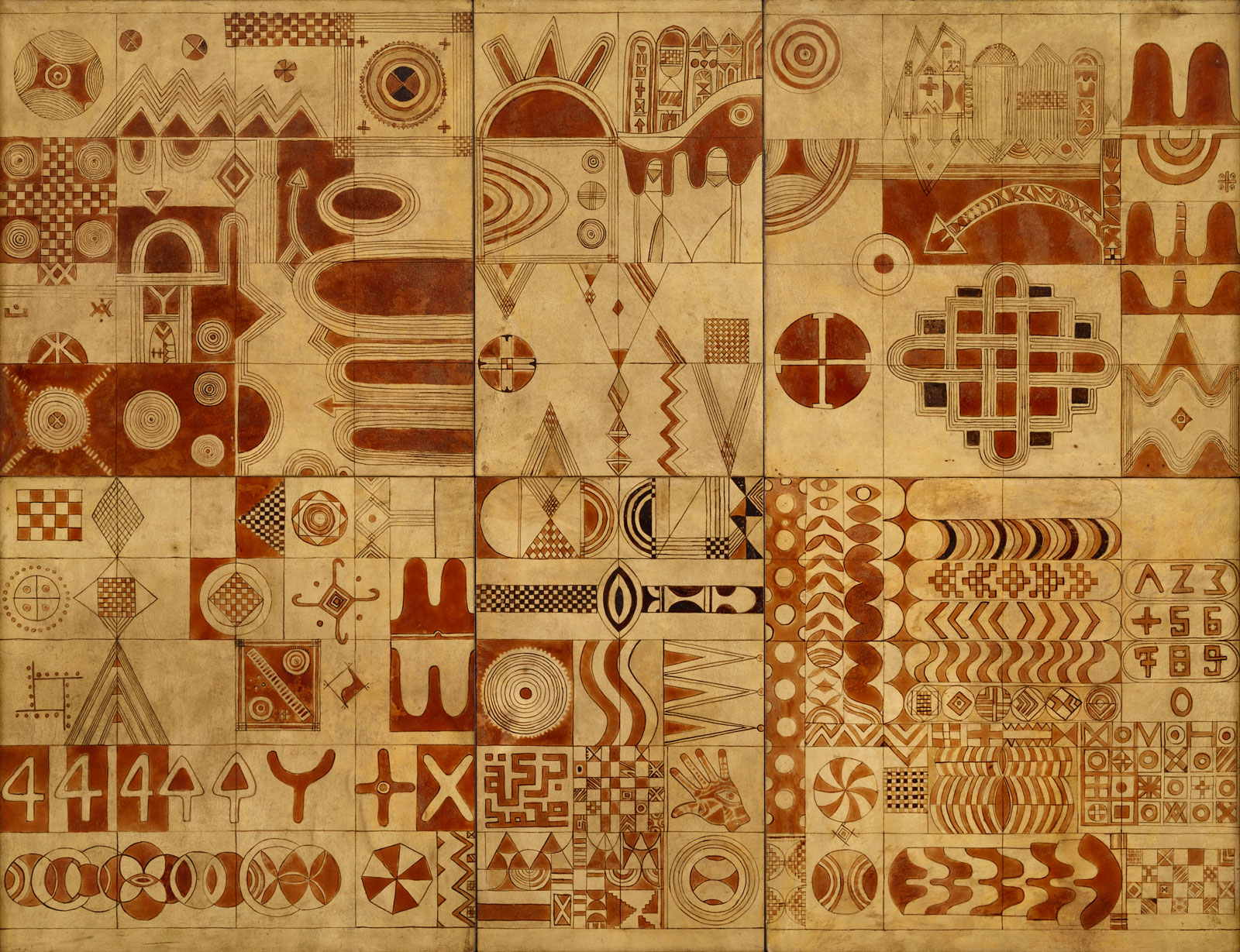

The pedagogical program at the Casablanca Art School expected the artistic practice to take on a more experimental dimension. The artists were motivated to bring an end to classical painting, and chose to close the gap which theoretically separated art and craftmanship. The two disciplines were, therefore, meant to be intertwined, leading to the establishment of some principles of the Moroccan modernity. The academic tradition was abandoned. The students and the artists found themselves free to exploit any kind of materials, such as natural pigments like henna, as well as bronze. They also used unexpected media, like leather as Farid Belkahia (1934-2014) did in the artwork entitled Patchwork Culturel (1979) (fig.4).

Figure 4 Farid Belkahia, Patchwork Culturel, 1979.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

The artists from the generation of the Casablanca Art Group eventually succeeded in merging the ‘culture savante’, i.e. fine-arts, and ‘culture populaire’11 – breaking the classical and Western hierarchy of the arts. Moreover, the artworks by these artists testified of the possibility to readapt the tradition in order to build the future, being the solid foundation for its development. It is important to recall that the modern Moroccan movement imposed itself as a post-colonial one, whose aspiration was also to demonstrate the cultural strength from a so-called ‘third-world’ country. Back then, the European hegemony was being weakened by the movements of independence in the former colonized territory.

It is generally acknowledged that tradition opposes modernity, in the sense that the second signals a change, or a break with the past. Nonetheless, in the 1960s and the 1970s, Moroccan tradition did not belong to the past. On the contrary, it turned into a great source of inspiration to create the Moroccan artistic modernity. Tradition characterizes the material culture of Morocco, which symbolizes the social cohesion among all Moroccans. In other words, it is visible in the different facets of popular life. Henceforth, using tradition as a reference point to conceptualize an original form of art, is also a form of claiming of the indigenous cultural legacy.

The artists-teachers from the Casablanca Art Group had a role to play in the development of the country’s future, as Mohamed Hamidi (1941-) asserted: “Furthermore, this work will be the best opportunity for the artist himself to flourish, for he will feel that he is in fact participating, through his own instrument of expression, in the transformation of the culture and the fundamental existence of an entire people”12. By celebrating the Moroccan tradition, they initiated a modern art movement, which could not match a few others in the West. Yet, most importantly, these artists regathered the whole Moroccan people around a culture, that was a reflection in itself, both rich and diverse.

Comments on The Making of the Moroccan National Culture