Last updated on Tue 26 June, 2018

SCRIPTED REALITY

10 HANOVER STREET | LONDON W1S 1YQ

JUNE 26 - JULY 3 2018

Lawrie Shabibi is excited to announce “Scripted Reality”, a group exhibition of six artists to be shown at 10 Hanover. This is Lawrie Shabibi’s first exhibition outside our gallery space in Dubai, and explores complex topics that shape the way we view the world today.

Scripted reality (sometimes also euphemized as structured realityin television and entertainment) is a subgenre of reality television with major or typically all parts of the contents being scripted, i.e. pre-arranged by the production company”

(“Scripted Reality, Structured Reality”, Buzzword from Macmillan Dictionary, sourced from wikipedia.com).

The lines between news and entertainment, fact and fiction, are being constantly eroded. In this post-internet age, the nature of information consumption is transformed from the edited polish of print media to a tailored feed of disconnected news reports, advertising and clickbait. Unfettered access to images without context 24/7, the layering of unconnected factoids and opinion transform the complex real world into a series of simpler artificial constructs. We look for things that confirm our beliefs, whether or not they may be true, and we find outlets increasingly willing to deliver those views. The delusion becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy - "fakeness" accepted as real.

The response of artists has, consciously or unconsciously, become part of this new zeitgeist. Their ideas and practices have developed either through sourcing material from cyberspace, questioning morality or amorality or looking at historical events through different lenses. “Scripted Reality” looks at how technology and the Internet has transformed ways of looking and understanding the world around us – and how artists have responded to this.

Two paintings by Ayman Baalbaki, from a series never before exhibited, taken from screen shots of online video games, show the interconnectedness between the domestic setting and the physical violence in the world, a lived experience familiar to Baalbaki, having experienced various wars and invasions in his native Lebanon. Ultra violent, with graphics increasingly realistic (if emotionally heightened), these digital images are as vivid as reality. They are a visual analogue to the sinister real “video games” played by military missile and drone operators.

Farhad Ahrarnia sources images of global and contemporary Middle Eastern topics of concern and discourse from media and cyberspace, digitally printing them onto cotton aida cloth, which he subsequently embroiders. Through the language of needlework, the images are subjected to an intense degree of scrutiny, in an attempt to deconstruct and agitate layers of meanings, power politics and hidden ideologies embedded, invested and consequently projected onto them. Often enlarging the pixels, Ahrarnia’s square micro-elements of digital picture production provide an additional geometric layer on the squared-up fabric. The two systems of co-ordinates, of textile and digital origin, provide the underlying geometric structure of the work. Embroidery for Ahrarnia is a way to re-vitalises these images - stitching as an articulation of space and time and also as an act of self-assertion on appropriated and apparently disconnected images.

Ramallah based Yazan Khalili’s work Hiding Our Faces Like a Dancing Wind, is a video piece currently on view in the exhibition Being: New Photography 2018 at MoMA through August 19, 2018. The video is a view of a computer screen, with one open window of a woman making various gestures captured through the lens of a phone camera that is itself being filmed. Facial recognition software pops up together with other Windows, text and files. The work is a screen seen through a number of other screens – and this interplay expose structures, operations, and algorithms that become the image itself. Speaking about his work, Khalili talks about how in today’s world we see images through the screen to the extent that each image takes on a life of its own – it can be shared, edited, stored etc - all within in a screen. As a result of this he has started to question the way in which images are produced, viewed and distributed. His video also appears to confuse the facial recognition system so that a sequence of ethnographic masks interrupt the frame. The work recalls colonial mechanisms of racial classifications and the construction of historical narratives, questioning the use of technology and its tendency to typecast.

Adel Abidin questions the socio-political implications of this age in his installation Politically Correct. Commissioned for his major museum solo at Helsinki’s Ateneum Art, the installation shows five versions of this statement being squashed until the words are hardly recognisable. With the proliferation of different social and political groups on the Internet, “political correctness” has been stretched in two extreme and opposite directions and people often hide their true beliefs or values in order to fit in. At times wildly divergent world-views sit side by side in an uneasy equilibrium. The views and opinions of the other are at best tolerated and at worst fiercely dismissed and scorned – Abidin’s sculpture is ironic, highlighting the vulnerability, weakness, and hypocrisy of decades of self-imposed restrictions on language that attempted to de-marginalize fringe groups.

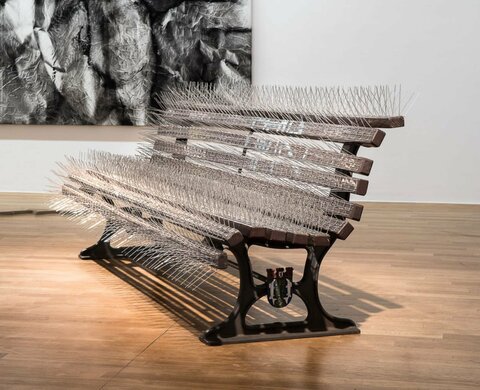

Berlin based Nadia Kaabi-Linke explores through her artistic practice the dominant narrative of history and its underlying contradictions. She presents a sculptural intervention on a found park bench covering it with spikes typically used on boundary walls to keep people and animals out. The bench confronts the viewer with its imposition and physicality. A benign place of safety and rest is quickly transformed into a hostile object; an everyday functional item becomes perplexing in its functionality and contradictory in its purpose. These opposing features capture the schizophrenia of Western values where “freedom” is the prevailing narrative and yet there is an underlying obsession with security, control and surveillance of movement in the public and private sphere as well as online.

Finally in Mounir Fatmi’s Kissing Circles, 09, the artist grapples with the speed at which mass-produced gadgets are rendered obsolete, replaced by even faster and more efficient devices. The artist makes use of white co-axial antenna cables, which he sees as quickly becoming outmoded, laying them out in circular geometric patterns presented in a plexi-box. The work is a shrine to the ideals of modernity, and to the narratives which are gradually erased from our memory. Its presentation, like a traditional museum display case, is a container of information that also functions as an archive in and of itself.

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art