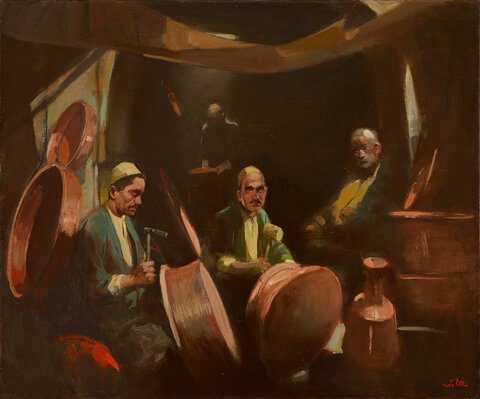

The Tent, 1956, is an abstract figurative painting executed with oil on canvas by Iraq’s renowned modernist painter Faik Hassan. It depicts four members of a Bedouin clan: three men and a woman. Two men dressed in light ochre gallabiyahs and black abayassit by the sandy desert floor against a bundle of jijiim[1]rugs, and one man stands further back. To the right, a veiled woman sits a short distance away from the two men in the front.Her pale pink robe, thobe, and peach-orange cloak, jubbah, lend highlights to the picture’s subdued color palette.At the painting’s upper register, a tent painted in maroon black and burnt umber stretches on the horizon below a Gitane blue sky.

Hassan paints the striped jijiimrugs with smooth, long strokes of maroon, cream, and burnt umber; the warm tones define the painting’s overall restricted color palette. A notable impressionist and a master in color blending, Hassan utilizes a palette of dull, earthy colors while retaining a sense of vibrancy. This is accomplished by toning the canvas using a middle hue, like burnt sienna, which creates warmth and allows light to come through the dulled tones of the piece. Hassan also maintains intensity by employing a repeating pattern through his choice of color and shapes. This can be seen across the striped pattern and the jijimrug colors, which are then transposed onto other elements like the tent, garments, and shadows to give an internal rhythm to the artwork.

While the figures are portrayed in a flat, angular, and almost cubist style, movement and texture are brought forward through the brush strokes’ direction. This is seen, for instance, in the woman's robe, where the orange paint comes through the rough horizontal brush strokes of the pale rose pink. Hassan’s stylistic choice also fits the organic elements he is trying to depict, such as the amorphousness of the gallabiyahand abaya, while prioritizing all the garments as distinct identity markers.

It is important to highlight the technical qualities of Hassan’s work because he prioritized these aspects in his exploration of the art form.[2]. Hassan, lauded by his peers as a master of technique[3], constructs his narrative by ensuring that line, color, and shape work together to create unity. He adds subtle contrasting elements that bring the painting to life, such as the bright line of green, which highlights the contours of the left man's kaffiyeh (headdress)and the planes of his face. We see the same green again in the folds of his robe, his face, and the woman’s face. The green then becomes tinted and dulled in the line, silhouetting the middle man’s robe. These shades and shadows tell us a story. They tell us that these men and women are sitting facing a fire, possibly at dusk. This is further justified by the lit panes of their faces, the brightness of the red in the jijimclose to the woman’s feet, as well as the darker blue tones of the sky and the orange outline of the cloud.

The Tentreflects Hassan's commitment to explicitly nationalist subjects and themes – Iraqi Bedouins, in this case – while exploring the role that color, technique, and style can play in cultivating a modern Iraqi style. This is in tandem with the objectives of ‘the Pioneers,' an artist group he founded and led in 1950, focusing on skill, techniques in color and lines, and primitive expressiveness.[4].

Within this painting, we can see a myriad of influences that Hassan carefully and skillfully samples: for instance, the realistic yet stylized figures resonate with the 13th-century Islamic pictorial traditions like the illustrations of Iraqi-Arab painter Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti’s[5] in maqamat al Hariri, or the assemblies, depicting scenes of ordinary daily life.[6]Furthermore, there are parallelisms with post-impressionist styles such as fauvism and cloisonnism[7]with its focus on dark contours, flat shapes, and artificial colors. In addition, there is a clear intellectual intersection with nationalistic movements, such as Russian neo-primitivism, which looked to folk art and prehistoric artifacts to forge a distinct national art form.[8]. In a similar vein, Hassan's work during this period privileged depictions of Iraqi peasants and Bedouins’ daily life and brought them to life by drawing upon his cultural heritage, Islamic artwork, and European approaches.

Sources:

signed in Arabic front lower left