Printmaking is a versatile and captivating art form that has a rich history dating back centuries. From the early Cylinder seal prints in Mesopotamia (3200 BCE), fabric prints in Egypt (1 CE), woodblock prints of China and Japan (618 CE – 907 CE) to the intricate etchings of the European Renaissance, printmaking has evolved and diversified around the world, encompassing a wide range of techniques and styles. In this overview, we will explore the fascinating history of printmaking, and delve into the various types and techniques that have shaped this dynamic and enduring art form. Over the centuries, printmaking has continued to evolve and innovate, with artists experimenting with a wide range of techniques and materials to create prints that are both visually striking and conceptually thought-provoking. The four types of printmaking techniques include: Intaglio, Relief, Planography, and Stencil or Silkscreen.

An Overview of the Four Main Types of Printmaking

Intaglio

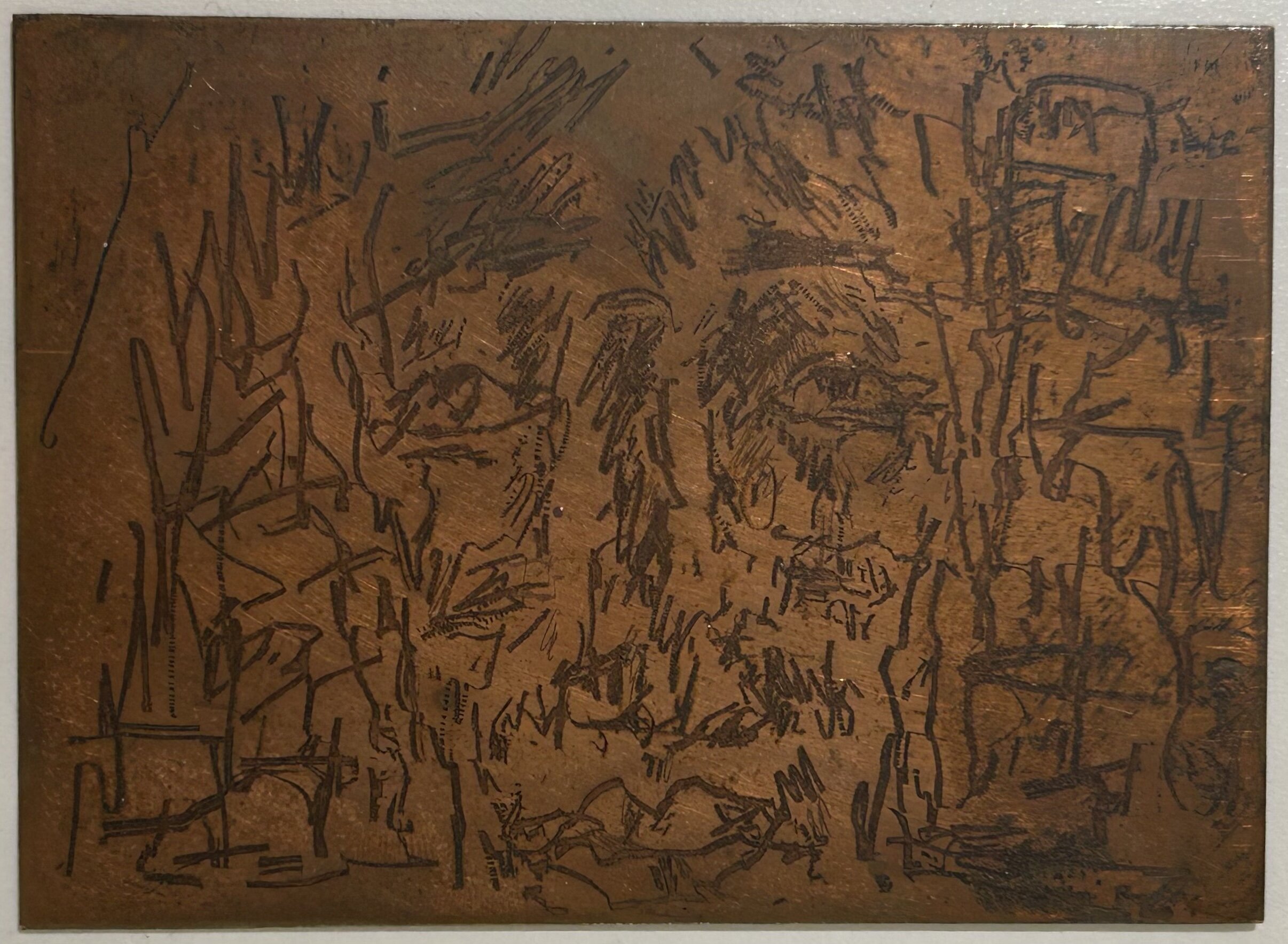

In intaglio printmaking, the image is incised or etched into a surface, typically a metal plate like copper, zinc, aluminum, steel, or even plastic. The plate is then inked, and the surface wiped clean so that ink remains only in the incised lines. Paper is then pressed onto the plate under significant pressure, transferring the ink to the paper. Examples of intaglio techniques include etching, engraving, dry point, mezzotint, and aquatint.

Relief printing involves carving away areas from a block or plate so that the ink only adheres to the raised surfaces, which are then pressed onto paper. The most common material used for relief printing is linoleum or wood. Woodcuts and linocuts are popular examples of relief printing techniques. Woodcuts involve carving into the surface of a woodblock, while linocuts use linoleum for a softer material to carve into.

Planography

Planographic printmaking, also known as lithography, is based on the principle that oil and water do not mix. A flat surface, usually a smooth stone or metal plate, is treated so that the image areas attract oily ink while repelling water. The image is then transferred to paper through a press. Lithography is known for its ability to create detailed and multi-tonal images.

Silkscreen (or Serigraphy)

Silkscreen printing involves a stencil method where a fine mesh screen is used as a support for ink, with the design areas blocked off to create the image. Ink is forced through the mesh onto the printing surface (usually paper). Silkscreen allows for vibrant colors and is often used in commercial printing, such as posters and apparel. Each of these printmaking techniques offers artists a unique set of tools and creative possibilities, allowing for a diverse range of artistic expressions.

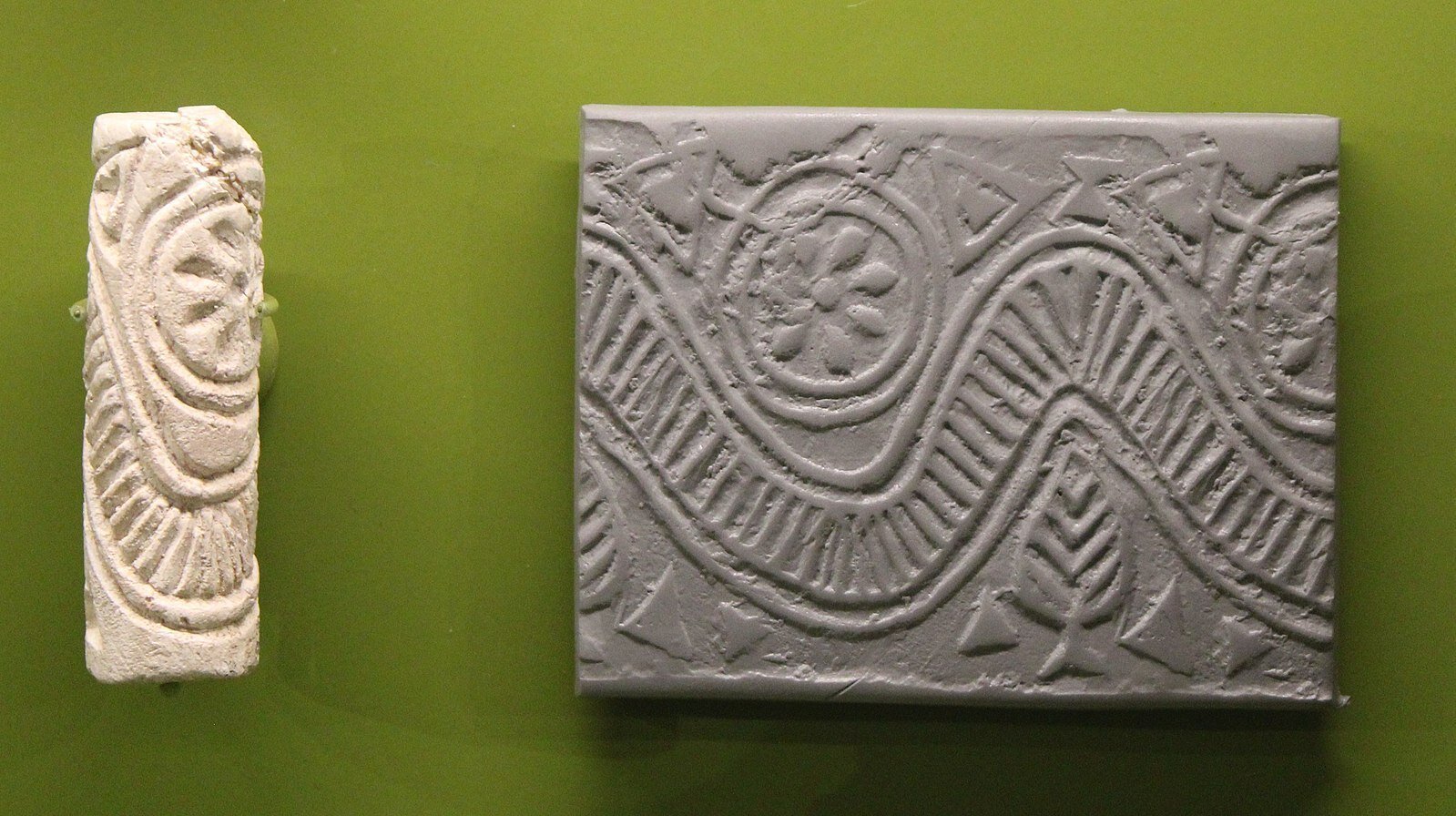

Stamp & Cylinder Seal Printing – (Mesopotamia)

We can trace the first two categories of printmaking, relief and intaglio impression, to 3200 BCE with the invention of stamp and cylinder seal printing, 300 years after the creation of the first known writing system, Cuneiform, in southern Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq. During this period, rulers sought to memorialize themselves and their gods in the palaces and temples they built by stamping an inscription onto building bricks.

To do so, Mesopotamians created a stone mold, where they would carve away the areas that are not to be printed, leaving behind a raised surface of the image intended to be printed – a technique known as relief. They would then stamp the soft clay of the bricks with the carved stone before firing it to leave the impression indented beneath the surface. In a similar but opposite technique, Mesopotamians formed cylinder seals from stone, marble, gold, silver, or semiprecious stones. They would engrave or incise into the cylinder’s surface (or matrix) the desired design, a technique known as intaglio. This mold was then rolled over soft clay, thus imprinting a continuous raised impression of the design above the main surface. Pierced through from end to end to be worn on a string, cylinder seals functioned as administrative signatures to notarize clay documents and were embellished with images and cuneiform writing.[1]

Early Textile Printing and the Introduction of Paper – (Egypt & China)

Moving beyond the cylinder seal imprints of ancient Mesopotamia, the development of fabric printing in 1st century Egypt and 3rd century China introduced both woodcut printing and the mediating medium of dye or ink to the printmaking process. Early textile printing was practiced in 1st century Egypt using mordant, a mineral salt that adheres to fiber which bonds natural dyes to fabric.[2] The fabric, stamped with mordant, was then dipped into dye and removed, creating reverse printed designs on the fabric.[3][4]

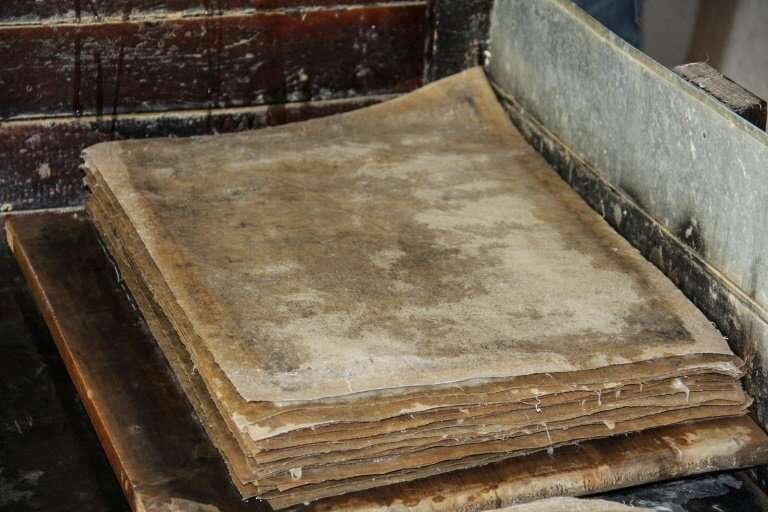

The creation of paper was a crucial development that led to many of the printmaking techniques we know today. First recorded in 105 CE, the papermaking process was developed in the royal courts of the Han Dynasty of China by soaking and pressing plant fibers, which were then dried on wooden frames in sheets[5]. Papermaking spread via the Silk Road to Samarkand, present-day Uzbekistan, by the early 8th century, and from there, subsequent innovations made their way through Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, and eventually Europe.

The Arab mix used to create paper was different than the ingredients used in the Chinese paper making process, which were a mix of hemp and other raw fiber, mulberry tree bark, bamboo pulp, rosewood, silk, and some rags. In one experiment in early 19th century, it was noted that the collection of examined papers from 950-1050 CE that came from Fayyum, Egypt was made of flax fiber (from flax plant and used to produce linen fabric), instead of bast fiber (inner bark of a variety of plants).[6] Since it was more affordable and accessible than tablets or parchment, paper would serve as the primary medium for printmaking for centuries to come.

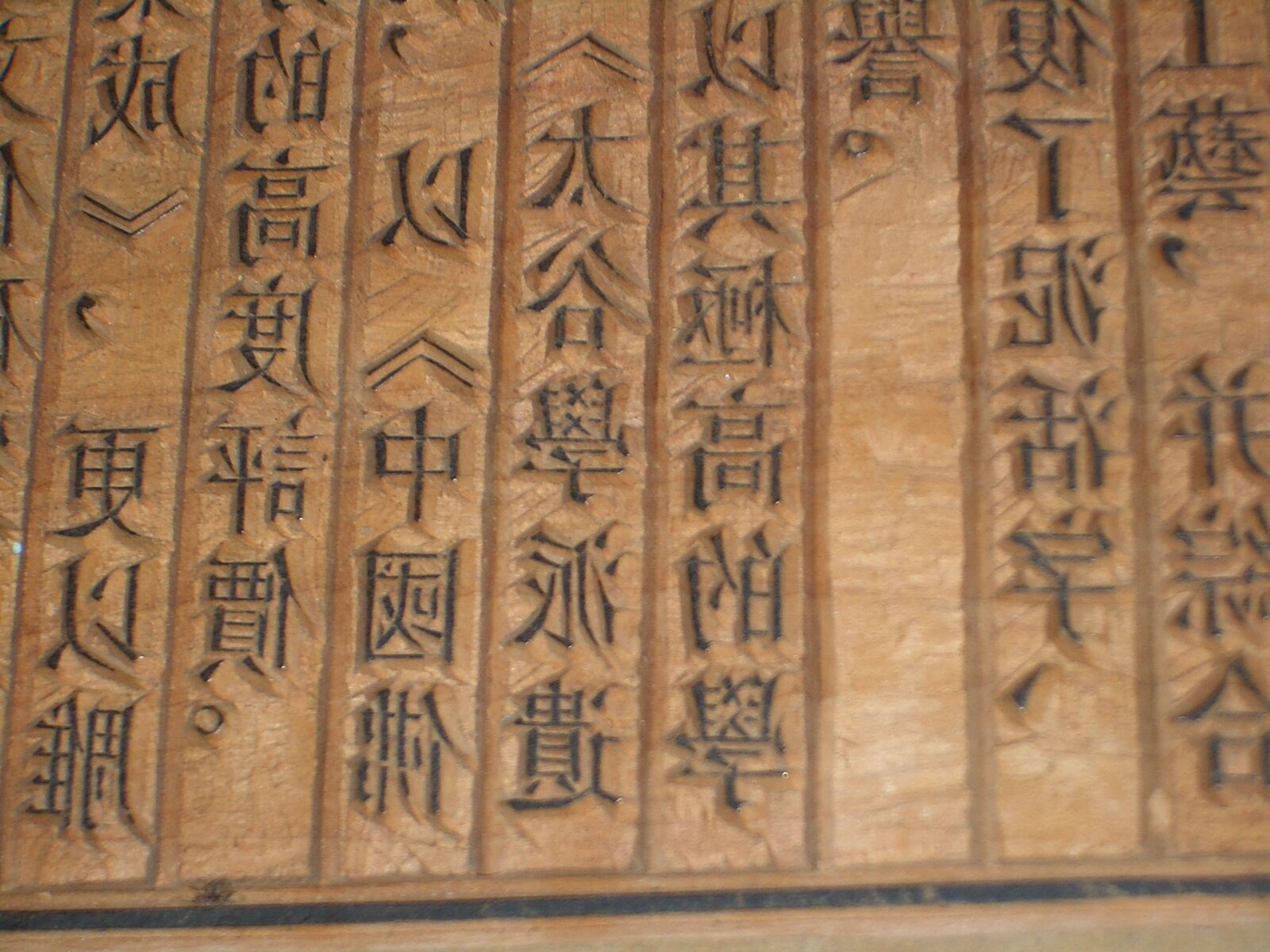

Woodblock Printing & Moving Type – (China)

After paper, the next major development in printmaking was the invention of mechanisms for book printing. Originally used for printing designs on fabric, woodblock printing for written texts on paper emerged in China around 600 CE and was developed through the century to print religious texts and holy images.[7] In 868 CE, the world’s earliest known printed book was produced in China, a copy of the Buddhist religious text The Diamond Sūtra. The book, which is a Chinese translation of a text written in Sanskrit, is comprised of seven paper panels, including the sacred teachings of Mahayana Buddhism, a form of Buddhism common in China, Japan, and Southeast Asia.[8]

Two centuries later in 1041 CE, Chinese farmer Bi Sheng developed a moving-type printing press. Chinese symbols (type) were sculpted into porcelain clay cubes and hardened in a kiln (a thermally insulated oven). The individual symbols were arranged on an iron frame to spell out a message, coated in ink and printed on paper. The movable rearrangeable nature of the type or letter blocks enabled the widespread publication and distribution of religious texts as well as later technological and educational books throughout China. The proliferation of books in East Asia also increased demand for illustrations, pushing the development of intricate woodcut prints.[9]

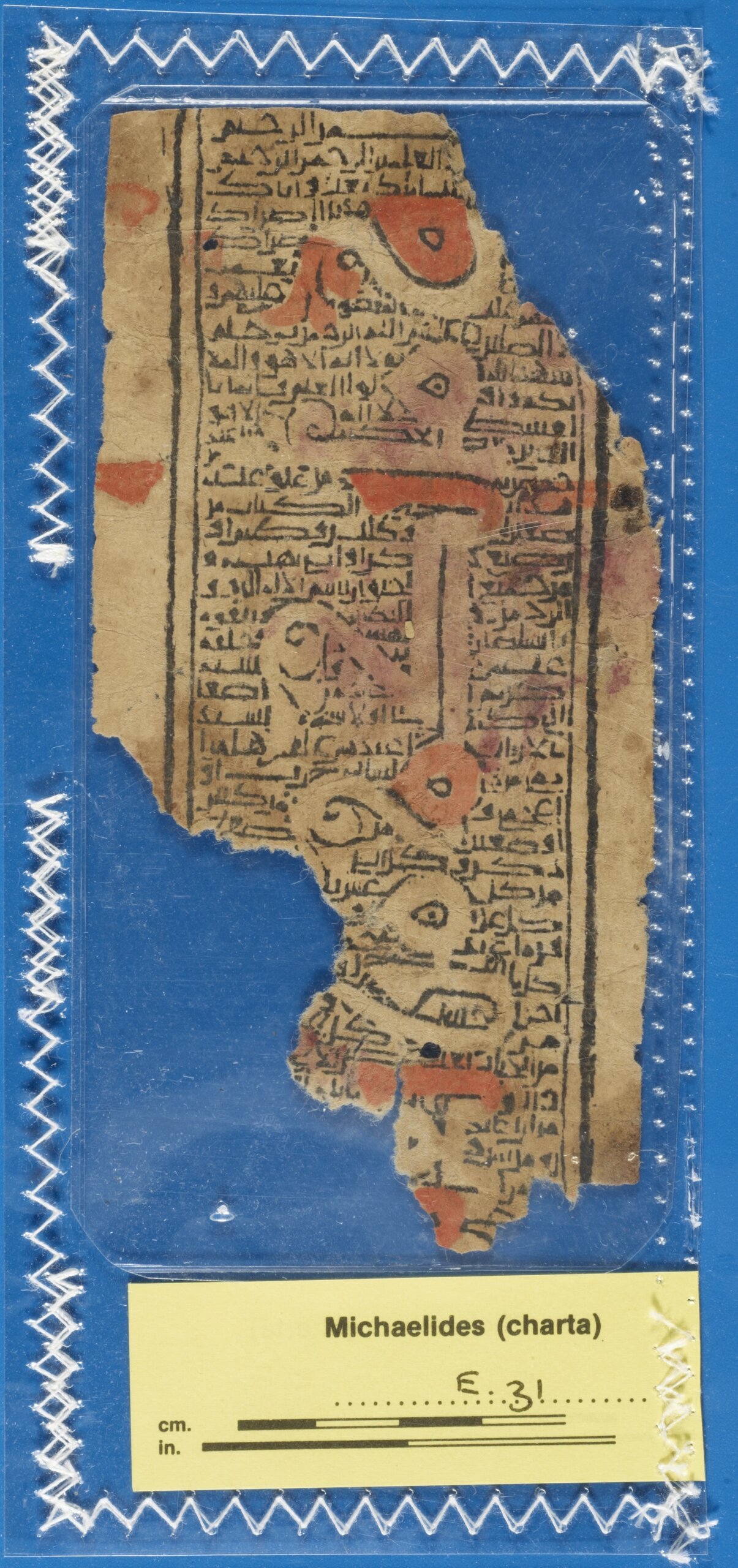

‘Tarsh’ Printing in the Middle East – (From Iran, Al-Andalus, Syria, and Egypt… to Italy)

An often-forgotten chapter in the history of printmaking occurred between the 9th and 14th centuries CE with small-scale experiments in type printing on paper, referred to as tarsh, as noted by 10th century Iranian poet, and travel writer Abu Dulaf al-Khazraji. Tarsh involved carving printing blocks, likely coated in molten tin, to print Quranic passages and religious texts onto paper strips used as amulets. These mass-produced amulets, sold to the illiterate public, emerged as a novel invention in the region, and seem to have come about without evidence of the influence of Chinese book-printing.

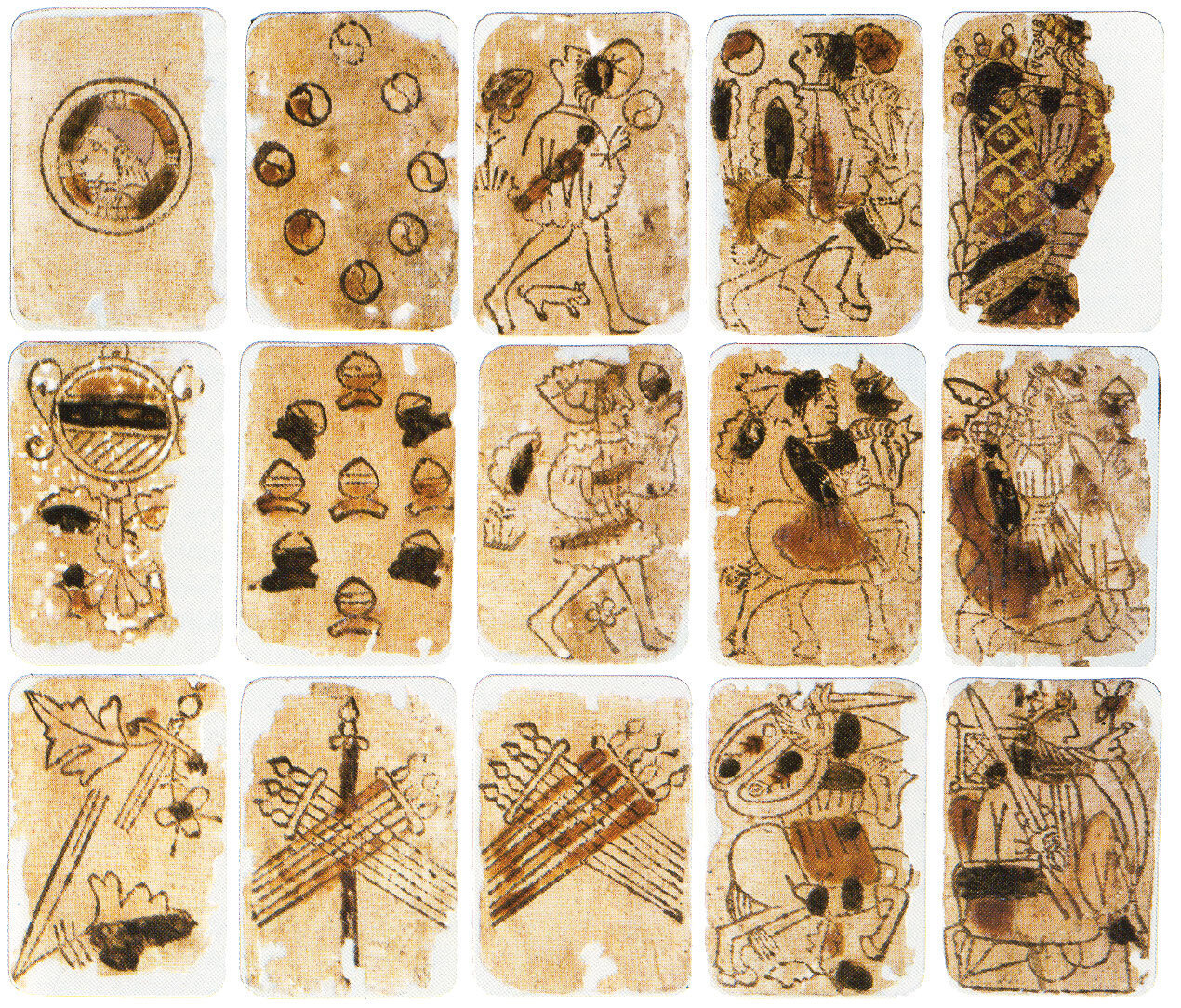

Other early printmaking trials included 10th century royal decrees in Al-Andulus and 12th century paper currency in northern Syria. By the early 14th century, Persian official Rashid al-Din documented Mongol-controlled printing in Ilkhanate Iran and the brief use of printed paper money in Tabriz in 1294 CE. While Arabic text printing did not flourish in this period (9th to 14th century), printed design and images on textiles thrived in 13th century Mamluk Egypt due to trade with India, leading to the spread of woodblock printing technology to Italy by the late 1300s. This technology gained popularity in Europe for printing playing cards and devotional images, possibly influencing the term "tarocchi" (tarot cards) from the Arabic "tarsh".[10]

48-card woodblock printed pack of cards featuring an early suit system derived from early Arabic cards from the Mamluk Sultanate from the Fournier Museum at Vitoria-Gasteiz Spain c. 1400 (https://www.wopc.[1] [2] co.uk/spain/baraja-morisca-early-xv-century-playing-cards)[3] [4]

Developments in the Art of Printmaking in Europe – (Germany)

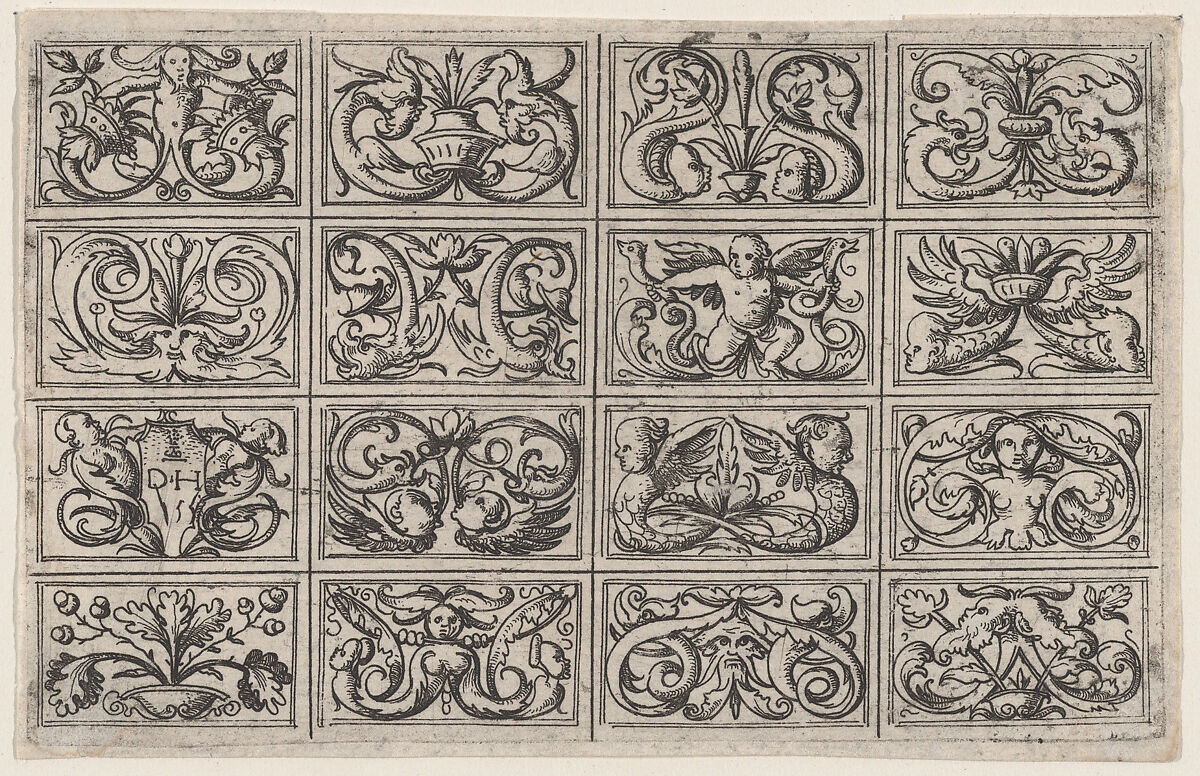

After paper and woodblock technology reached the Mediterranean shores through Muslim traders, it spread to the European continent. In Germany, printmaking made some large developments through metalworkers who began printing on metal plates, which were more durable than wood blocks. In the 1430s, gold and silversmiths skilled in engraving metal for jewelry and armor developed intaglio printing, whereby a metal plate is engraved and the ink from the incised design is transferred onto paper.

Early print masters Martin Schongauer and Albrecht Dürer, who were both from German goldsmith families, became highly skilled in the intaglio printmaking technique of engraving.[11] In this process, lines are cut into a copper or zinc plate to hold ink, allowing for the creation of intricate images on paper. This new technique enabled a proliferation of art prints throughout the continent, particularly in Italy where print houses were flourishing.

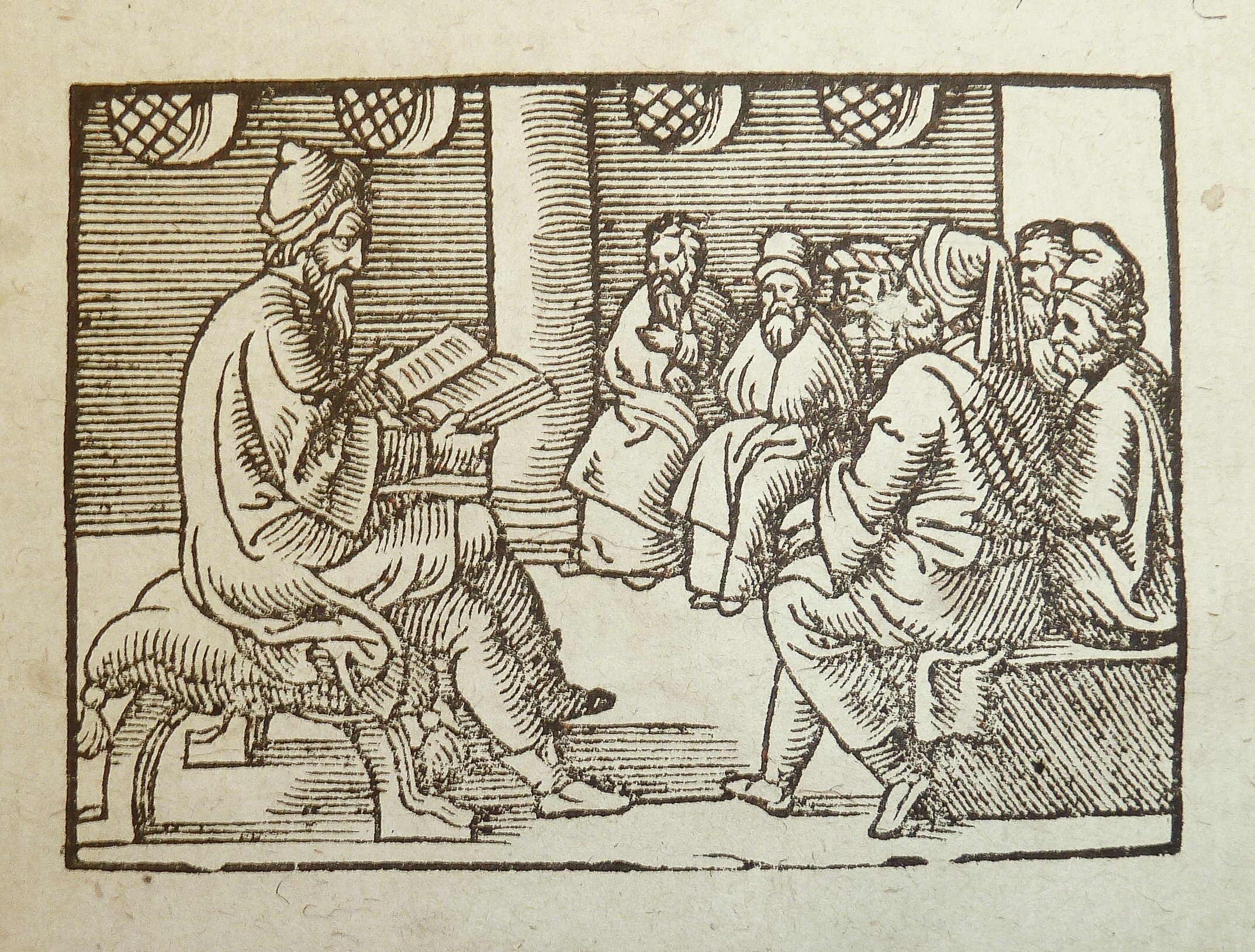

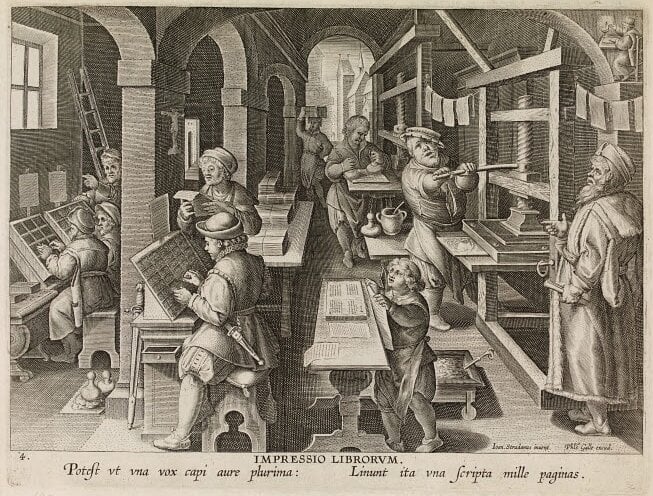

Just as fine-art prints were taking off in Germany and Italy, Johann Gutenberg created the printing press in Germany in 1440 CE. Gutenberg formed type blocks by pouring molten metal into letter molds fashioning a tiny block with the relief character on top, enabling the creation of identical multiples of the same letter. These durable metal-type blocks were then sorted into cases to form sentences and used to make up pages. Like the Chinese movable type prior, the type could be rearranged and reused in any combination; however, Gutenberg modified the standard water-based ink to an oil-based ink, which transferred type more effectively.

An illustration of a Flemish printer's shop, Impressio Librorum. Made in Antwerp, 1580-1605 CE. (British Museum, London) (cc) https://www.worldhistory.org/Johannes_Gutenberg/

Furthermore, Gutenberg adapted the traditional wine press – a device used to extract juice from crushed grapes for winemaking – to print on paper by remodeling it for the purpose of printing. He did so by mounting inked type cases onto the press and constructing a mechanism that allowed for the application of even pressure onto the paper beneath, which resulted in even and precise transfer of ink and produced high-quality and uniform prints. This allowed printing to happen much faster than block printing or manuscript creation, catalyzing a book printing revolution in Europe, enabling the proliferation of ideas, text, and image to be replicated swiftly and shared with wide audiences. Due to the new market for books, printing technologies and techniques advanced at an accelerating rate.[12]

Renaissance Print Developments: Etching: Dry Point, Engraving, Etching, Mezzotint & Acquaint – (Germany & Belgium)

In the 14th to 17th centuries CE, the drive to depict classical antiquity, architecture, and science across Europe spurred a surge in printmaking and the development of new intaglio techniques, as publishing houses began producing illustrations, diagrams, and maps became popular in an era characterized by travel, scientific discovery, and mass publishing.

These cultural changes led to the furthering of the printed image through intaglio processes such as drypoint, engraving, and etching, as well as the development of intaglio techniques such as mezzotint, and aquatint.

By the 1470s, artists began experimenting with drypoint, directly incising a copper or zinc plate with a steel needle, which scraps or ‘pushes up’ the metal to create a ragged edge or ‘burr’. The resulting textured grooves hold ink for printing and produce lines that are distinguished by their softness.[13] Another important characteristic of drypoint is that in the process of printing, the pressing of the plate onto paper or fabric wears down the ‘burrs’, which means that a small number of proofs (less than fifty) can be produced from the plate – this made the proof number of a drypoint print more significant, and the low-number proofs of an edition more desirable.[14]

As noted earlier, engraving was adapted from the craft of goldsmithing. It developed simultaneously in Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy during the 15th century CE.[15] In terms of process, the engraver transferred a design onto a copper or steel plate, and incised the surface with a tool called a burin, which created furrows that could then be retraced to increase their depth and thus the darkness of their lines. To maintain clean lines, burrs and ridges were scraped off.

In 1500 CE, German armor embellisher Daniel Hopfer pioneered the art of (acid) etching by adapting the technique of using acid to etch designs into rounded steel armor plates by applying it to flat plates that could be printed. The metal plate is coated with an acid-resistant wax-like material called a ground. After the design is worked into the ground, an etching needle is used to create the lines as opposed to digging into the metal plate. The plate is then exposed to or dipped in an acid bath, which etches into where the metal is exposed, creating the incised design for printing. The acid baths could be repeated as many times as needed in order to get the line depths required by the artist. This process allowed for more versatility and variety of technique compared to other intaglio methods, and it was appealing to many more artists since it is easier, and essentially only required that the artist know how to draw.

The 17th century saw the decline of engraving as artists were drawn more to etching due to its more expressive qualities, ease of technique (no need to meticulously carve into a metal plate), efficiency for producing prints which required less labor, and possibility of producing a larger number of consistent prints before the plate wore down.

The evolution of art prints led to a desire for improved tonal imagery. This resulted in the development of Mezzotint in 1642 CE by Ludwig von Siegen, which allowed half-tones to be printed by roughening the metal plate with thousands of tiny dots made by a rounded, fine-tooth metal tool known as a rocker to create an even incised texture that can hold ink for printing. A design is then selectively rubbed down or burnished to various degrees of smoothness, thus removing the texture. Burnished areas will hold less ink and appear lighter in the final print. Mezzotint was used mostly in the 18th and 19th centuries, but with the advent of newer and less laborious techniques, it lost its favor within fine arts.

.jpeg)

Additionally, Aquatint, which advanced acid etching technology to include planes of tone instead of lines, was developed in 1650 CE by Jan van de Velde IV, in Amsterdam. The most common Aquatint technique is: heating grains of rosin (resin extracted from pants) that are applied to a metal plate to adhere them. The plate is then bathed in acid, which etches or ‘bites’ around the tiny individual grains creating a plate with an incised texture that holds ink. A range of tones can be achieved by selectively stopping out areas of the design by applying resist over the areas that are to remain lighter and successively dipping the plate in acid. This creates different areas of different tones. This method was used by many known painters and sculptors from this period who were also printmakers such as Albrecht Durer, Rembrandt van Rijn, and Francisco Goya as they combined different print techniques in innovative ways.[16]

.jpeg)

[1]

Andrea Seri, "Adaptation of Cuneiform to Write Akkadian," Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond 32 (2010): 85-98.

Oya Topçuoğlu, Iconography of Protoliterate Seals (n.p.: 2010).

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Stamp Seals of the Hittite Old Kingdom, accessed August 31, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/327799.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cylinder Seal and Modern Impression, accessed August 31, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/329090.

Kadim Hasson Hnaihen, "The Appearance of Bricks in Ancient Mesopotamia," Athens Journal of History 6, no. 1 (2020): 73-96.

[2] According to Roman author and philosopher Pliny the Elder who describes the process in his Natural History, “After fulling, the white materials are painted, not with colours, but with substances that absorb pigments”

[3] Woolman, ‘Textile Printing’; Louis, ‘Painting of Fabric’.

[4] The earliest printed textile found by archaeologists is a child’s linen tunic with a woodblock printed diamond and star pattern, from the 4th century AD at Achmim Egypt, and printed textiles in red, black and powdered gold have been found in Iran from the 6th century

[5] The earliest known paper is traced to 200 BCE in China, but was only recorded 300 years later. Prior to the development of paper, various materials such as clay tablets, tree bark, papyrus and parchment were used.

[6] Maya Shatzmiller, "The Adoption of Paper in the Middle East, 700-1300 AD," Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 61, no. 3 (2018): 461-492.

[7] "The Invention of Woodblock Printing in the Tang and Song Dynasties," Asian Art Museum, accessed August 31, 2024, https://education.asianart.org/resources/the-invention-of-woodblock-printing-in-the-tang-and-song-dynasties/.

[8] These are “Wisdom” texts that, together with their commentaries, are known as the Prajnaparamita (“Perfection of Wisdom”). It was created using seven woodcut prints with the first being a woodcut illustration showing the Buddha expounding the sutra to an elderly disciple.

[9] Thomas Francis Carter, The Invention of Printing in China and Its Spread Westward (New York: Columbia University Press, 1925); Thomas Christensen, “Guttenberg and the Koreans,” in River of Ink: An Illustrated History of Literacy (Counterpoint, 2014); “Diamond Sutra Frontispiece,” Dunhuang, accessed May 31, 2024, http://idp.bl.uk/collection/9C9BE31B79574FC88CEC5569171D8177/?return=%2Fcollection%2F%3Fterm%3Ddiamond%2Bsutra; "The Invention of Woodblock Printing in the Tang and Song Dynasties," Asian Art Museum.

[10] Geoffrey Roper, “Arabic Printing Culture,” in Encyclopedia of Mediterranean Humanism (2014), https://encyclopedie-humanisme.com/?Arabic-printing.

[11] Phil Sanders, Prints and Their Makers (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2020); Ad Stijnman, Engraving and Etching 1400-2000: A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking Processes (London: Archetype Publications, 2012); Wendy Thompson, “The Printed Image in the West: History and Techniques,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/prnt/hd_prnt.htm.

[12] Thomas Francis Carter, The Invention of Printing in China and Its Spread Westward (New York: Columbia University Press, 1925); Christensen, “Guttenberg and the Koreans,”; Prints and Their Makers; Robert Hoe, A Short History of the Printing Press (Good Press, 2021); Oregon State Library, “Gutenburg Press,” Special Collections & Archives McDonald Collection, accessed May 31, 2024, https://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/mcdonald/incunabula/gutenberg/.

[13] Thompson, ‘The Printed Image in the West’; Sanders, Prints and Their Makers.

[14] Ralph Mayer, The HarperCollins Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques, 2nd ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 1991).

[15] Mayer, Art Terms and Techniques.

[16] Stijnman, Engraving and Etching, 1400-2000; Sanders, Prints and Their Makers; Thompson, ‘The Printed Image in the West’, 2003.

Comments on General History and Evolution of Printmaking: Part 1