The History of Printmaking Across the Arab World

Co-written by: Iona Stewart, Boushra Batlouni, Wafa Roz

(Part of the Prints & Printmaking Exhibition at DAF 2024)

Printmaking has a long and rich history in today's Arab region. While this artistic tradition has often been overshadowed in global discourse, its five-thousand-year evolution is intricately linked to the broader region's cultural, religious, and technological developments. From the ancient Mesopotamian cylinder seals to contemporary fine art printmaking, we will explore the trajectory of printmaking (including banknotes, text, literature, ornamental and fine art) in today's Arab region, while examining its aesthetics, historical underpinnings, technological advancements, and role in shaping socio-political narratives and artistic innovation.

Mesopotamian Stamp & Seal Printing

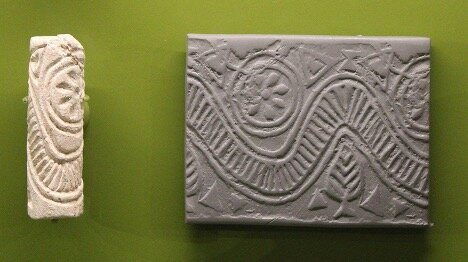

We can trace the first two categories of printmaking, relief and intaglio impression, to 3200 BCE with the invention of stamp and cylinder seal printing, 300 years after the creation of the first known writing system, Cuneiform, in southern Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq. During this period, rulers sought to memorialize themselves and their gods in the palaces and temples they built by stamping an inscription onto building bricks.

To do so, Mesopotamians created a stone mold where they would carve away the areas that were not to be printed, leaving behind a raised surface of the image intended to be printed, a technique known as relief. They would then stamp the soft clay of the bricks with the carved stone before firing it to leave the impression indented beneath the surface. In a similar but opposite technique, Mesopotamians formed cylinder seals from stone, marble, gold, silver, or semiprecious stones. They would engrave or incise the desired design into the cylinder's surface (or matrix), a technique known as intaglio. This mold was then rolled over soft clay, thus imprinting a continuously raised impression of the design above the main surface. Pierced through from end to end to be worn on a string, cylinder seals functioned as administrative signatures to notarize clay documents and were embellished with images and cuneiform writing.[1]

Early Textile Printing

Moving beyond the cylinder seal imprints of ancient Mesopotamia, fabric printing developed across India, Egypt, and China, with each culture developing similar techniques to transfer patterns onto textiles. In China and Egypt, some of the earliest printed fabrics date back to 3000 BCE, possibly even earlier. During the Indus Valley Civilization (between 3300 BCE and 1300 BCE), India was a center of block printed textiles production, with evidence suggesting that the Egyptian and Indian development of textiles during that period was connected through trade via the Red Sea.[2]

During the 1st century, the Roman writer and philosopher Pliny the Elder discussed textile printing in Egypt in Natural History (Book 35, Chapter 42).[3] He described a technique used by the Egyptians to produce colored designs on fabrics. This method involved applying dyes to textiles using blocks or stamps with engraved patterns. The fabric was first treated with a mordant to fix the dyes, and then the design was stamped onto the cloth.

In his writings, Pliny notes that this technique allowed for the creation of highly prized intricate and multicolored patterns. He described the process as an early form of what we would now call "block printing," a highly developed method in Egypt that contributed to the region's reputation for producing luxurious textiles. These printed textiles were used in clothing and for decorative purposes. One of the earliest Egyptian printed cloth we have on record is dated to the 4th century, and was most likely produced in the textile centers of Alexandria, Panopolis, Oxyrhynchus, or Tinnis.

Across the Arab region, printmaking on fabric as an artistic practice employed techniques of woodcut printing and mediating dye or ink, which would remain the backbone of global printing for another 500 years. Syria, for instance, was a key node of the Silk Road and was known for its textile production since Roman times. Oral histories gathered by art historian Rania Kataf recount that hand-printed fabric with woodblock prints was a popular commodity in Syria over the last centuries (until very recently with the advent of war),[4] with Aleppo, Hama, and Damascus as its main arteries.

Aleppo was especially renowned for the habari, a silkscreen-printed silk scarf worn to cover hair on special occasions or wrapped around the forehead as a symbol of beauty and luxury.[5] Artisans used silk mesh stretched over a square wooden frame fitted with a paper stencil. To cover the large square scarves, they applied the mesh four times. This enabled fabric dye to be pressed through the screen onto the scarf, revealing a pattern in the stencil's negative space.

On the other hand, Hama, a city in Syria, was known for its simpler white cotton fabrics, which featured black floral or geometric designs created using woodblock printing, typically used as domestic textiles for beds and tables. Artisans would carve out the negative space of a design into a block of wood, which, when coated in ink and pressed onto the fabric, would print the raised area of the block. Artisans carved designs in relief (removing the negative space) on wooden blocks. By coating these blocks with ink and pressing them onto the fabric, they transferred the raised design on the block to create the printed patterns. These Hama-printed textiles were sold to Bedouins as far as Iraq, and were dyed with darker pigments to make the fabrics more suitable for travel, with the black ink symbolizing the strength of the men of Hama.

In Damascus, woodblock-printed fabrics were produced in Khan al-Dikkeh in Souq Midhat Pasha by a family named al-Tabbaa, which translates to 'the ink printers'.[6] In Southern Iraq, Karbala was also recognized for more colorful woodblock prints on fabric in the form of mosques, ornate motifs, and poetic texts, which were used for decorative purposes on religious holidays.[7]

Invention of Paper & Papermaking

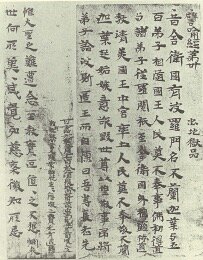

The papermaking process was developed in the royal courts of the Han Dynasty of China (206 BCE – 220 CE) and first recorded in their dynastic records in 105 CE. The Chinese created paper using hemp, mulberry tree bark, bamboo, rosewood, and silk. They soaked and pressed the plants' fibers or pulp, then dried them on wooden frames in sheets.[8] Before fiber-made paper, papyrus and parchment were the earliest invented writing surfaces. Papyrus, extracted from the central pith of a Papyrus plant, was invented as far as 2900 BCE in Egypt. Parchment, made out of animal skin and named after the ancient Greek city of Pergamum, was first commercially produced around the 2nd century BCE.

Arab Muslims encountered papermaking when they conquered Central Asia in the 8th

century CE. The technique spread via the Silk Road to Samarkand, present-day Uzbekistan. There, papermaking technology was further advanced by combining silk waste, mulberry bark, and bamboo sprouts, which were boiled, ground, and pressed into thin sheets to create high-quality paper for making copies of the Quran.[9][10]

By 794 CE, papermaking had spread to Baghdad, where it became more efficient through the creation of the first water-powered paper mill,[11]

enabling mass production. These innovations spread to Damascus, Cairo, and eventually to Europe, when the Umayyad Caliphate (661 CE – 750 CE) controlled Southern Spain from 714 CE as Al-Andulus.[12]

Paper is cheaper and easier to source than tablets or parchment, so it was and continues to be the medium for printmaking across centuries.

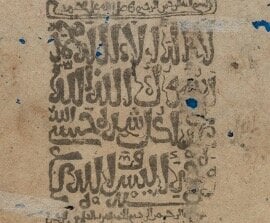

Early Experiments in Block-Printed Amulets: Tarsh (9th – 14th

Century)

Arabic block printing must have begun in the 9th or 10th century but continued to the 14th century. Tarsh was a block printing form that seemed to have disappeared after that period. Tarsh prints are usually fitted inside a metal cylinder and worn as an amulet on chains around the neck, with long Quranic quotes and other religious texts made to ward off evil.[13] One community that had peddled these amulets belonged to a medieval Islamic underworld of beggars and swindlers called the Banu Sasan, who would produce and sell Tarsh to the poor and illiterate populace.

How Tarsh prints were created is still being debated, but one of the most likely printing methods was that the maker of the Tarsh shallowly engraved the minute text into a wet clay tablet. After it dried, he applied a thin sheet of tin and pounded it into the grooves of the letters or, alternatively, poured molten tin onto it – a repeated process using the same tin.[14] This technique potentially explains why none of the prints have survived. Another possibility why the technique did not survive is because the technology used to make Tarsh was seen as inferior and not worthy of being applied to the refined world of those of higher social status, which may have kept it insulated from the rest of society.

Research continues about Tarsh block printing as part of the history of Arab printmaking and printmaking more broadly, with some scholars speculating that the Italian word Tarocchi, which refers to tarot cards – the earliest European printed artifacts – may have originated from the Arabic 'Tarsh.'[15]

Coinage and Block Printing on Paper Currency

Coinage has long been a significant aspect of the Arab world’s economic and cultural history, with the process of coining involving the use of punches or dies – engraved tools made of hard material with designs engraved onto their surface, which were pressed into heated metal to create identical reproductions of a design. The Umayyad Caliphate (661 CE – 750 CE) was the first Islamic dynasty to issue coinage, which allowed them to maintain economic stability and authority over their Empire and convey religious and political messages.

By the early 14th century, Muslim societies were well-acquainted with printing techniques, as the famous historian and statesman Rashid al-Din demonstrated. Vizier to Ghazan Khan, the Mongol ruler of Iran, Rashid al-Din highlighted in the first volume of his world history in 1307 that printing was known in the Muslim world.[16] His writings also provide evidence of printing experiments within Iran. Notably, in 1294, Ghaikhatu, the Mongol ruler of Iran, attempted to introduce block-printed paper money. This paper currency bore inscriptions in both Arabic and Mongolian. However, the introduction of paper money faced severe challenges: it was met with scepticism from merchants, was rejected by the military, and ultimately led to public unrest.[17]

Printmaking in the Ottoman Empire (15th – 18th Century)

European accounts regarding the development of printmaking often portrayed the Ottoman Empire as resistant to technological advancement. This resistance was sometimes interpreted as a sign of cultural or intellectual backwardness. For example, printing was seen as an inherently "Western" and "Christian" development, with some European historians overlooking or dismissing the Ottoman adoption of printing altogether.[18] Moreover, the Orientalist version of events often ignored the economic, cultural, religious, and political factors that influenced the Ottoman reluctance to adopt printing.

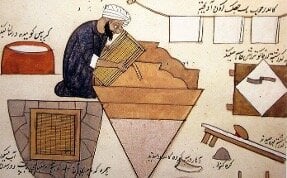

The Ottoman resistance to printmaking technology was due to several concerns. Mainly the potential disruption and impact on the livelihoods of a vast network of scribes, calligraphers, and illuminators who played a significant role in producing Quran manuscripts.[19] These artisans were integral to creating functional manuscripts that were considered luxury items and symbols of status among the elite.[20]

Manuscripts, especially those containing the Quran and other religious texts, were revered for their content, artistry, and the spiritual merit involved in their creation.[21] The act of handwriting was imbued with piety and considered a form of worship. Scribes engaged in a meditative practice that honored sacred texts.[22] The transition to print, perceived as a mechanical and impersonal process, raised concerns about diminishing the spiritual value and personal devotion involved in manuscript production, which was seen as a higher, more respected art form.[23]

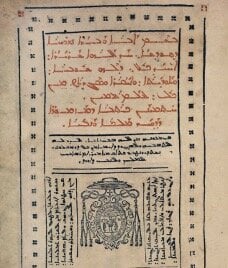

There was a fear that the mechanical reproduction of holy texts could lead to errors and inaccuracies, potentially corrupting the sacred words.[24] This issue was prevalent in the early books printed in Arabic – often printed in Italy since it was a leading center of technology at the time, and there were extensive trade routes and diplomatic connections with the Ottomans. For example, the first book printed in Arabic type was ‘Kitab Salat al-Sawa'i’ or the Book of Hours (potentially for Arabic-speaking Christians in the Levant). The book was produced in Fano, Italy, in 1514. It had a type so unrefined and unattractive to the readers that it was near incomprehensible.[25] Then, when the first Quran was printed in Arabic type, in Fano, by the Venetian printer Alessandro Paganino around 1537 or 1538,[26] it was also plagued by numerous errors critical to the Arabic script, such as misplaced diacritical marks and confusion between similar letters.[27] Scribes' precision and care in transcribing religious texts – especially the Quran and related literature – were viewed as safeguards against errors and integral to maintaining the Quran's textual integrity.[28]

These mistakes in Arabic script were likely due to the printer's inadequate understanding of the Arabic language. Thus, the early mal-constructed Arabic printed books did not appeal to the reader, reducing their potential as commercial investments.[29] Furthermore, the Ottomans were cautious of technological innovation that might compromise the tightly regulated control or spread of information. The Empire's leadership was wary of print technology's potential to facilitate the unauthorized dissemination of information that could undermine the existing social order or stir dissent.[30]

Role of Ottoman Armenians, Greeks, and Jews in Printmaking Development

Ottoman Armenians, Greeks, and Jews played an essential role in the earliest development of printing in the Arabic script; yet, they did not hold the same concerns regarding the sacred nature of the Arabic language that Muslims held. Through the 15th and 17th centuries, these non-Muslim communities printed books in the Ottoman Empire in Armenian, Syriac, Hebrew, Greek, and Roman movable type printing.[31]

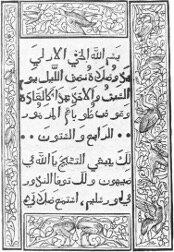

Outside of Istanbul, small-scale printing projects began in monastic communities such as the Lebanese Monastery of Saint Anthony's Press in Quzhayya, located in the Zgharta District in the North Governorate of today's Lebanon. The first printed book by the St. Anthony's Press was published in 1610; it was a book of psalms in Syriac written in Garshuni (Arabic transliterated in Syriac letters since Syriac was the language of the Church, but most worshipers spoke Arabic).[32] Though the psalms do not include illustrations, they include the seal of the printing press on the front cover and are stamped with decorative flourishes throughout.

In 1734, a Lebanese printer and typographer, Abdallah Zakher (1684-1748), set up the first printing press in the Middle East. He was a Melkite Christian at the time of the Church's re-establishment of Communion with Rome. Zakher’s printing press “used Arabic movable types and was installed in 1733 in the motherhouse of the Basilian Chouerite Order, the monastery of Saint John the Baptist at Choueir, or Dhour El Shuwayr, near Khinchara, in Mount Lebanon, where it still can be visited.”[33]

Ibrahim Müteferrika, the Printing Press, and Reform in Ottoman Istanbul

In the 18th century, modernization movements in the Ottoman Empire began to prioritize the mass production of books, spurring the development of printing technologies despite earlier hesitations about printing in Arabic script. Modernization efforts aimed to cultivate a more extensive and better-educated military and administrative class, strengthen the state, and challenge traditional political and religious structures.[34]

In 1727, Ibrahim Müteferrika, a diplomat and philosopher, presented Wasilat al-Tiba’a, or The Utility of Printing to the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Ahmed III (1703-1730); the essay relays the benefits of printing to the Muslims and Ottomans.[35] Convinced by Müteferrika’s proposal, Sultan Ahmed III, an avid reader, skilled in calligraphy, and knowledgeable on history and poetry, authorized the opening of a printing press in Istanbul for printing in Arabic type using custom-made fonts referred to as ‘Turkish incunabula.' The Press, called Dârü’t-tıbâ’ati’l-ma’mûre, and best known as the Basma Khāne or printing house, operated between 1729 and 1742, producing 17 works in 22 volumes.[36] Müteferrika's first book, an Arabic-Turkish dictionary in two volumes, was published on January 31, 1729, with an initial print run of 500 copies.

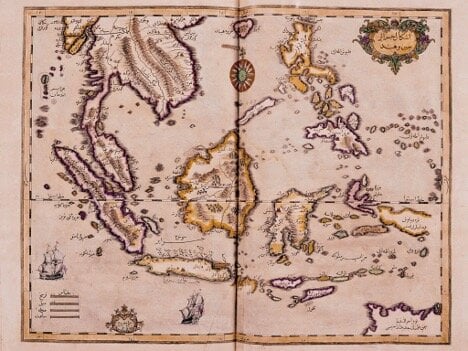

The press was limited to books on secular topics, such as history, geography, language, and government – some illustrated with maps or engravings. This edict protected the many professional scribes of Istanbul and helped educate and empower a new class of officials more aligned with the state's goals and less dependent on the traditional religious elites.[37] Notably, the Müteferrika press printed the first book with figural illustrations, History of the Discovery of America, which featured 13 prints and four maps.[38] This publication initiated a culture of printing images alongside books.

Consequently, Istanbul became the center of Muslim Arabic printing in the 18th century, highlighting print's potential as a medium for distributing ideas. It made education more accessible and promoted the spread of printing technology throughout the region.

[1]

Andrea Seri, "Adaptation of Cuneiform to Write Akkadian," Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond 32 (2010): 85-98.

Oya Topçuoğlu, Iconography of Protoliterate Seals (n.p.: 2010).

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Stamp Seals of the Hittite Old Kingdom, accessed August 31, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/327799.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cylinder Seal and Modern Impression, accessed August 31, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/329090.

Kadim Hasson Hnaihen, "The Appearance of Bricks in Ancient Mesopotamia," Athens Journal of History 6, no. 1 (2020): 73-96.

[2] Ayesha U. Shaikh, “Made in India, Found in Egypt: Red Sea Textile Trade in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 2023, accessed September 1, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rstti/hd_rstti.htm.

[3] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 35, Chapter 42, accessed August 31, 2024, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D35%3Achapter%3D42.

[4] Syrian Heritage, “The Ink That Lasts Forever: Textile Printing in Syria,” accessed September 1, 2024, https://syrian-heritage.org/the-ink-that-lasts-forever-textile-printing-in-syria/.

[5] Syrian Heritage, “A Woman with a Screen-Printed Headscarf Called Habari,” accessed September 1, 2024, https://syrian-heritage.org/a-woman-with-a-screen-printed-headscarf-called-habari/.

[6] Syrian Heritage, “The Ink that Lasts Forever”.

[7] Rafa Nasiri, Contemporary Graphic Art (Beirut: The Arab Institute for Research and Publishing, 1997), 38.

[8] The earliest known paper is traced to 200 BCE in China but was only recorded 300 years later. Before the development of paper, various materials such as clay tablets, tree bark, papyrus, and parchment were used.

[9] Maya Shatzmiller, “The Adoption of Paper in the Middle East, 700–1300 AD,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 61, no. 3 (2018): 461–92.

[10] Shatzmiller, “The Adoption of Paper in the Middle East”.

[11] ‘History of Papermaking Around the World’; ‘Paper in Ancient China’.

[12] Thomas Christensen, “Guttenberg and the Koreans,” in River of Ink: An Illustrated History of Literacy (Counterpoint, 2014); Phil Sanders, Prints and Their Makers (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2020).

[13] Richard W. Bulliet, "Medieval Arabic ṭarsh: a forgotten chapter in the history of printing," Journal of the American Oriental Society (1987): 427-438.

[14] Bulliet, "Medieval Arabic ṭarsh”.

[15] Geoffrey Roper, “Arabic Printing: Printing Culture in the Islamic Context,” in Encyclopedia of Mediterranean Humanism, Spring 2014, https://encyclopedie-humanisme.com/?Arabic-printing.

[16] "A Missing Link," in Arabic and the Art of Printing: A Special Section, Aramco World, November-December 1980, https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/198102/arabic.and.the.art.of.printing-a.special.section.htm.

[17] “A Missing Link”.

[18] Nil Pektaş, "The Beginnings of Printing in the Ottoman Capital: Book Production and Circulation in Early Modern Istanbul," Studies in Ottoman Science 16, no. 2 (2015): 3–32.

[19] Pektaş, "The Beginnings of Printing in the Ottoman Capital,” 9-10.

[20] Pektaş, 7.

[21] Pektaş, 8-9.

[22] Pektaş, 8-9.

[23] Pektaş, 8-9.

[24] Pektaş, 9-10.

[25] Paul Lunde, "Arabic and the Art of Printing: A Special Section," Aramco World, January/February 1981, accessed August 31, 2024, https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/198102/arabic.and.the.art.of.printing-a.special.section.htm.

[26] Pektaş, 5.

[27] Pektaş, 5.

[28] Pektaş, 9-10.

[29] Titus Nemeth, "Overlooked: The Role of Craft in the Adoption of Typography in the Muslim Middle East," in Manuscript and Print in the Islamic Tradition, ed. Scott Reese, vol. 26 of Studies in Manuscript Cultures, ed. Michael Friedrich, Harunaga Isaacson, and Jörg B. Quenzer (2022): 21.

[30] Pektaş, 10-11.

[31] Roper, “Arabic Printing”; Barbara Henning and Taisiya Leber, “Print Culture and Muslim-Christian Relations,” in Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 18. The Ottoman Empire (1800–1914) (Brill, 2021), 39–61, 42, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004460270_004.

[32] Hala Auji, “Picturing Knowledge: Visual Literacy in Nineteenth-Century Arabic Periodicals,” in Making Modernity in the Islamic Mediterranean (Indiana University Press, 2022), 73–94, 79; Pascal Zoghbi, “First Printing Press in the Middle East,” 29LT (blog), 2012, https://blog.29lt.com/2010/06/16/1st-printing-press-in-me/.

[33] “In Honorem: Deacon Abdalla Zakhir Made the First Arabic Press — Eastern Christians Were Key to Arab Renaissance.” Accessed August 31, 2024. https://phoenicia.org/zakhir.html; “Al-Shamas Abdallah Zakher,” Gallerease, accessed September 1, 2024, https://gallerease.com/en/artists/al-shamas-abdallah-zakher__a0b1a708bc0e.

[34] Roper, “Arabic Printing”.

[35] “Sultan Ahmet III Permits Printing on Secular Topics by Müteferrika While Protecting the 4000 Scribes in Istanbul,” History of Information, accessed September 1, 2024, https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=472.

[36] Sean E. Swanick, “İbrahim Müteferrika and the Printing Press: A Delayed Renaissance,” Bibliographical Society of Canada 52, no. 1 (2023): 269–92, https://doi.org/10.33137/pbsc.v52i1.22262.

[37] Roper, "Arabic Printing”.

Comments on The History of Printmaking Across the Arab World: Part 1