Arab Printmaking in the 20th Century

Globally, and in the Arab world, the 20th century saw a rapid proliferation of print culture for an increasingly literate society with greater access to print materials for producing fine art prints and publishing literature in printing houses. The production of books, posters, and fine art prints, which were relatively recently rooted in the region, became very intertwined.

The avant-garde art thrust of this period and the transnational political movements following postcolonial independence compelled innovation in artistic methods and techniques – both manual and mechanized – and experimentation with a broader range of materials. It allowed fine art printmaking artists to be more tactile in their artistic experimentation and to disseminate their art to wider audiences. Thus, fine art printmaking emerged as a thoroughly modern medium, essential to the creative and political condition of the last century.

While modern Arab artists initially focused on painting and sculpting, fine art print culture became vital in shaping national and transnational visual languages and identities. In particular, Rafa Nasiri (1940-2013), an Iraqi artist and pioneer printmaker, traces the genealogy of fine art printmaking’s traction and boom in the Arab world to the 1960s and the social and political revolutions of that decade that led to a proliferation of transnational graphic arts: “Just as graphic art was affected by (all of these) artistic and intellectual events and revolutions, it was also affected by the results of modern industrial and political developments.”[1]

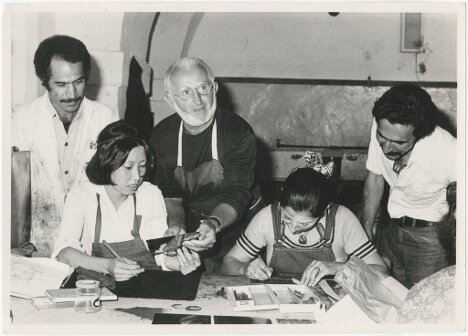

Nasiri himself left for Lisbon, Portugal, just a week after the Six Day Arab defeat, or the Arab-Israeli War in 1967, for a Gulbenkian Foundation scholarship – a two-year training at the Portuguese Engravers Co-operative (Gravura). In Portugal, Nasiri was also exposed to an environment of civil unrest in Europe during 1968, punctuated by demonstrations and strikes linked to leftist movements worldwide, which inspired a generation of protest art, including posters and graffiti.[2]

The importance of fine art printmaking in transnational anti-imperial and protest movements gave printmaking a popular edge. It was a revival of printmaking that Nasiri and his Iraqi colleagues, like Salem al-Dabbagh and Hashim Samarchi, who trained in Portugal, wanted to bring back to Iraq's artistic and political atmosphere.[3] The diversity of fine art printmaking techniques and processes made this art exceptionally flexible and rich. It provided endless possibilities for expression. As such, artists began recognizing printmaking's potential for intense innovation and experimentation, reflecting the cultural drive for the new and the modern. They also acknowledged its potential to bring art to the people, to move modern Arab art away from the intelligentsia, and to make it visible and part of a national visual language of Arab modernity.

Many pioneering Arab artists of the early 20th century learned some basic printmaking techniques as part of classical Western art education while studying abroad. Such as Jewad Selim, Hafidh Droubi, Mahmoud Mokhtar, and Fateh Moudaress, to name a few. Though this certainly has significance, these artists did not continue practicing printmaking on their return home as they focused on creating national modernist art. They also did not have access to printmaking studios, nor did they print with simple means like wood or linoleum. Instead, pioneering artists such as these helped found fine arts departments focusing on painting and sculpture in their universities with new modernist yet nationalist curricula. There was no mention of printmaking departments, though. It was not until the beginning of the 1960s that fine art printmaking in the Arab world began to take root. Though we have touched on the Arab region, the focus will be on two countries, Iraq and Lebanon.

20th Century printmaking in Iraq & The New Vision Group

The consolidation of printmaking as an art form in Iraq has no linear narrative but many threads that built up the printing culture among Iraqi artists, including the influence of Polish printmaking and graphic art, Chinese woodblock, silkscreen posters, and publishing.

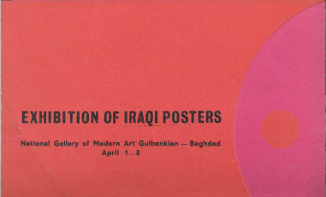

In 1959, the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad invited Polish artist Roman Artemowski to teach a printmaking course after organizing an exhibition of Polish contemporary Art in Baghdad, including prints. During this period, the institute acquired two old printing presses, and the Polish art and design magazine Projekt became very influential for Iraqi artists' printing, with artists Dia Al Azzawi and Saleh al-Jumaie traveling to Poland for international poster biennales. Artemowski organized a graphics exhibition at the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad, which then traveled to East Germany,[4] under the title Modern Iraqi Graphic Art.

During this same period, an exhibit of Chinese works of ivory, copper, silk, ceramics, and printmaking was held at the Institute of Fine Arts in 1959. Having been moved by this exhibition, young artist Rafa Nasiri applied for a government scholarship to study painting and printmaking in China. Along with four other students, including fellow artist Tariq Ibrahim, Nasiri studied at Peking University in Beijing, from 1959-1963, where he came to specialize in Chinese woodblock printing. Although Nasiri was taught by Artemowski, since he was studying abroad during this period, he had Chinese rather than Polish influences. Nasiri would go on to head the Graphic Department at the Institute of Fine Arts Baghdad in 1974.[5]

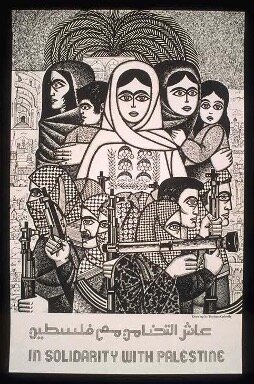

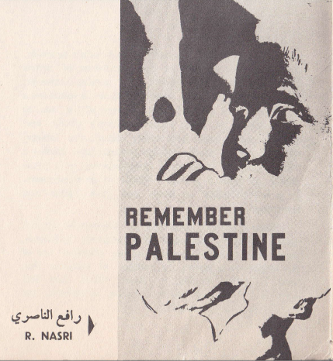

Simultaneously, artists in Baghdad were learning silkscreen printing from master printer Nadhim Ramzi. From the 1950s, Iraqi artists used silkscreen in posters and cards, such as Jewad Selim's silkscreen greeting cards from 1958.[6] Nadhim Ramzi proposed the first exhibition of silkscreened poster art at the National Gallery of Modern Art in 1971, which took place through the printing facilities at his atelier.[7] Print artists sought to take art outside the walls of museums and galleries to the public, such as the pre-Islamic Hanging Odes of Mecca as silkscreen posters, collaborative art prints with contemporary poets, or art print homages to Palestinian resistance and suffering.[8] This reflected the goals of contemporary artists concerned with their cultural and political environment.

Rafa Nasiri co-founded the New Vision Group (al-ru'iya al-Jadida) in 1969, along with fellow artists Dia Al Azzawi, Saleh Al Jumaie, Ismael Fattah, and Hashim Samarchi. What distinguished it from previous groups was the use of new media and techniques, such as printmaking and graphic art, especially the artistic poster. The New Vision Group did not call for common stylistic trends; its members came together around intellectual and political ideas. The 1967 Six Day War, Arab defeat, or the hazima was fresh in their minds; they aimed at a closer relationship of art and politics, foregrounding notions of revolution, freedom, anti-imperialism, social justice, and political change. In the group's manifesto, Dia Al Azzawi writes: "We reject the artist of partitions and boundaries. We advance. We fall. But we will not retreat. Meanwhile, we present the world with our new vision [...] We reject social relations resulting from false masks and reject what is given to us out of charity. We are the ones to achieve justification of our existence through our journey of change ...".[9]

Posters during this era were treated less as commercial tools and more as fine art prints, a method of communicating the aesthetics and ideals of local art movements to the urban public. For instance, Dia Al Azzawi, Hashim Samarchi, and Rafa Nasiri designed posters for the al-Mirbid Poetry Festival in Basra 1971, creating 30 original prints and distributing each work individually by hand. In this period, artists experimented extensively with medium and form through the possibilities opened by printmaking processes, expanding their outreach and impact.[10] Posters were easy to reproduce and circulate, making them ideal visual communication tools for disseminating knowledge. In Iraq, art prints emerged alongside a surge in collective visual communication – both commercial and artistic – offering a gateway to introduce modern art to a broader public.

20th Century Printmaking in Lebanon

Similarly, many factors consolidated printmaking as an art in Lebanon, from studies in engraving abroad to local publishing houses and poster culture. Halim Jurdak, trained initially at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Art (1953-1957), went on to continue his studies in Fine Art at Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France, where he focused on engraving and received the first prize in the print category of the academy's annual exhibition. He began teaching at the Lebanese University in 1966, developing the printmaking curriculum and training the next generation of printmakers, such as Jamil Molaeb and Mohammad El Rawas.[11]

After further training in printmaking at the Slade, London, El Rawas developed the printmaking studio at the Lebanese University, introducing Intaglio techniques such as etching on metal. In 1990, he established a printmaking studio at the American University of Beirut in the Department of Architecture and Design, equipping it with etching, engraving, and silkscreen studios. He taught another generation of printmakers, such as Bernard Haddad and Hassan Zahreddine.

Printmaking also took hold and reached the public as an art form through publishing houses in Beirut. Illustrated Arabic books in the mid-20th century interwove the Arab art scene with print culture after offset printing. They used lithography to transfer an image from a hydrophilic aluminum printing plate to a rubber blanket cylinder and then onto paper via inked rollers, making these illustrated Arabic books available due to developments in lithography. The publishing house Dar an-Nahar, led by Yousef al-Khal, commissioned artists such as Paul Guiragossian, Dia Al Azzawi, and Shafic Abboud to produce works printed alongside Arabic poetry and literature classics in his literature and art magazine Shi’r. These artists would also exhibit at Gallery One, established in 1963 by publisher Yousef al-Khal and his wife, the artist Helen Khal.[12]

During this period, artists began to explore the value of printing in their practice; both Dia Al Azzawi and Shafic Abboud would study fine art printmaking after this experience.

Art historian Zeina Maasri also highlights the role that the printing of political posters played in catalyzing artists to explore print as a medium of political art. Just as radical art collectives such as the Atelier Populaire in 1968 Paris, and the Black Panther Party in San Francisco were using printed art on the street, Palestinian revolutionary groups and the artists who supported the causes also began to use poster as a revolutionary art form, bringing together printmakers and artists from across the Arab world.

The intellectual and Palestinian Liberation Organization representative in France, Ezzeddine Kalak, writes that "Through posters, the [Palestinian] cause enters the homes of masses and resides in their eyes.”[13] Posters reproduced from Palestinian nationalist paintings and drawings became popular, such as paintings by Sliman Anis Mansour, Nabil Anani, Abdulrahman al-Muzayen, and Abdulhay Musallam Zarara. The convergence of Beirut's trans-local art and publishing scene infrastructures in the 1960s created the historical conditions that enabled the city's visual rise to become a concentrated site of printmaking shapes in solidarity with Palestine, where "Palestinian posters transformed Beirut's walls into a large exhibition," as noted by the Lebanese novelist and critic Elias Khoury.[14]

Conclusion

The history of printmaking in the Arab world is a rich tapestry woven through centuries of innovation, cultural interchange, and artistic evolution. The pivotal invention of paper and the establishment of water paper mills in Baghdad mark crucial milestones that transformed the capacity for documentation and artistic expression across the Arab world. As printmaking grew through various forms, such as the Tarsh block printing in Fustat and the adaptation of Mongol printing techniques for banknotes in Iran, non-Muslim Ottomans development of Arabic script printing further broadened the scope of print culture. This opened avenues for producing religious texts and educational materials that played significant roles in community life. The establishment of the first official printing press in Istanbul by Ibrahim Müteferrika, alongside Napoleon's introduction of movable Arabic type to Egypt, laid foundational stones for a burgeoning print industry that would eventually see a proliferation of print media throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Nahda period marked a renaissance not only in literary pursuits but also in visual culture, highlighting the integral relationship between print and society. The visual aspect of print became crucial to understanding the socio-political landscape of the region. The subsequent emergence of poster design as a form of social commentary and the establishment of fine arts printmaking studios in places like Iraq and Lebanon, besides other Arab countries, heralded a new era of artistic expression that embraced and innovated upon traditional methods.

Moreover, importing techniques such as metal intaglio and advanced silkscreen fine art printmaking from Western countries symbolized a significant shift that expanded the repertoire of Arab artists. Movements like the New Vision Movement in Iraq emerged, advocating for exploring new mediums and melding art and politics. This evolution reveals a response to historical circumstances and a spirited dialogue between heritage and modernity.

Thus, the arc of printmaking in the Arab world illustrates a story of resilience, creativity, and transformation – a narrative continuously underscored by the region's diverse cultural influences. As we look toward the future, the rich legacy of printmaking in the Arab world continues to inspire new generations of artists and thinkers, encouraging them to harness the power of print as a vehicle for social change and artistic exploration. The dynamic history and ongoing evolution of printmaking not only enriches our understanding of Arab cultural heritage, but also reaffirms the enduring relevance of this art form in reflecting and challenging the complexities of contemporary society.

Bibliography

al-Azzawi, Dia. “Graphic Design and the Visual Arts in Iraq.” In Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, edited by Anneka Lenssen, Sarah A. Rogers, and Nada M. Shabout, 370-371. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

“Al-Shamas Abdallah Zakher.” Gallerease. Accessed September 1, 2024. https://gallerease.com/en/artists/al-shamas-abdallah-zakher__a0b1a708bc0e.

Auji, Hala. Printing Arab modernity: Book culture and the American press in nineteenth-century Beirut. Vol. 7. Brill, 2016.

Auji, Hala. ‘Picturing Knowledge: Visual Literacy in Nineteenth-Century Arabic Periodicals’. In Making Modernity in the Islamic Mediterranean, 73–94. Indiana University Press, 2022.

Badghaish, Ahmad, Amal Omar, and Mohammad Khizal Mohamed Saat. “Investigate The Level of Awareness and Acceptance of Social Commentary Art Among the Public in The Arab Region.” KUPAS SENI: Jurnal Seni Dan Pendidikan Seni 11, no. 2 (2023): 10–22. https://doi.org/10.37134/kupasseni.vol11.2.2.2023.

Bulliet, Richard W. "Medieval Arabic ṭarsh: a forgotten chapter in the history of printing." Journal of the American Oriental Society (1987): 427-438.

Christensen, Thomas. “Guttenberg and the Koreans.” In River of Ink: An Illustrated History of Literacy. Counterpoint, 2014.

“Early Arabic Printing: Movable Type & Lithography.” Yale University Library Online Exhibits. April–June 2009. https://onlineexhibits.library.yale.edu/s/arabic-printing/page/printing_history_arabic_world.

Henning, Barbara, and Taisiya Leber. ‘Print Culture and Muslim-Christian Relations’. In Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 18. The Ottoman Empire (1800-1914), 39–61. Brill, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004460270_004.

Hnaihen, Kadim Hasson. "The appearance of bricks in ancient mesopotamia." Athens Journal of History 6, no. 1 (2020): 73-96.

Lenssen, Anneka, Sarah A. Rogers, and Nada M. Shabout. Modern art in the Arab World: Primary Documents PP 306-307. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

Lunde, Paul. “Arabic and the Art of Printing: A Special Section.” Aramco World, January/February 1981. Accessed August 31, 2024.

Maasri, Zeina. Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut's Global Sixties. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Maasri, Zeina. "The Visual Economy of “Precious Books”: Publishing, Modern Art, and the Design of Arabic Books." Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 40, no. 1 (2020): 95-113. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/755625.

Mejcher-Atassi, Sonja. “Unfolding Narratives from Iraq: Rafa Nasiri Book Art.”

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cylinder Seal and Modern Impression. Accessed August 31, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/329090.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Stamp Seals of the Hittite Old Kingdom. Accessed August 31, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/327799.

Miller, Meg. “Print.” Eye on Design. Accessed September 2, 2024. https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/design-for-and-from-communities-bahia-shehab-on-a-history-of-arab-graphic-design/print-100/.

Molaeb, Jamil Hammoud. Artists and Art Education in Time of War: Lebanon. PhD diss., The Ohio State University, 1989.

Mujani, Wan Kamal, and Napisah Karimah Ismail. ‘The Social Impact of French Occupation on Egypt’. Advances in Natural and Applied Sciences 6, no. 8 (2012).

Myers, Robert. "Painting the Theater of the East: Nineteenth-century Orientalist Painters and the Modern European Theater." Middle East Critique 18, no. 1 (2009): 5-20.

Nasiri, Rafa. 50 Years of Printmaking. Milano: Skira, 2013. ISBN 978-88-572-2023-9.

Nasiri, Rafa. Contemporary Graphic Art. Beirut: The Arab Institute for Research and Publishing, 1997. http://rafanasiri.com/Publication.aspx?id=7.

Nasiri, Rafa. Artist Books. Milano: Skira, 2016. ISBN 978-88-572-3341-3.

Nemeth, Titus. "Overlooked: The Role of Craft in the Adoption of Typography in the Muslim Middle East." In Manuscript and Print in the Islamic Tradition, edited by Scott Reese, vol. 26 of Studies in Manuscript Cultures, edited by Michael Friedrich, Harunaga Isaacson, and Jörg B. Quenzer (2022): 21.

Pektaş, Nil. "The Beginnings of Printing in the Ottoman Capital: Book Production and Circulation in Early Modern Istanbul." Studies in Ottoman Science 16, no. 2 (2015): 3–32.

“In Honorem: Deacon Abdalla Zakhir Made the First Arabic Press — Eastern Christians Were Key to Arab Renaissance.” Accessed August 31, 2024. https://phoenicia.org/zakhir.html.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Book 35, Chapter 42. Accessed August 31, 2024. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D35%3Achapter%3D42.

Reese, Scott. Manuscript and Print in the Islamic Tradition. De Gruyter, 2022.

Roper, Geoffrey. ‘Arabic Printing : Printing Culture in the Islamic Context’. In Encyclopedia of Mediterranean Humanism, Spring 2014. https://encyclopedie-humanisme.com/?Arabic-printing.

Sanders, Phil. Prints and Their Makers. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2020.

Seri, Andrea. "Adaptation of cuneiform to write Akkadian." Visible language. inventions of writing in the Ancient Middle East and beyond 32 (2010): 85-98.

Shabout, Nada M. Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2007.

Shaikh, Ayesha U. “Made in India, Found in Egypt: Red Sea Textile Trade in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. March 2023. Accessed September 1, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rstti/hd_rstti.htm.

Shatzmiller, Maya. "The adoption of paper in the Middle East, 700-1300 AD." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 61, no. 3 (2018): 461-492.

Shehab, Bahia, and Haytham Nawar. A History of Arab Graphic Design. American University in Cairo Press, 2020.

Smitshuijzen AbiFarès, Huda. “Experiments in Modern Arabic Typography.” In Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, edited by Anneka Lenssen, Sarah A. Rogers, and Nada M. Shabout, 302-303. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

“Sultan Ahmet III Permits Printing on Secular Topics by Müteferrika While Protecting the 4000 Scribes in Istanbul.” History of Information. Accessed September 1, 2024. https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=472.

Swanick, Sean E. “İbrahim Müteferrika and the Printing Press: A Delayed Renaissance.” Bibliographical Society of Canada 52, no. 1 (2023): 269–92. https://doi.org/10.33137/pbsc.v52i1.22262.

Syrian Heritage. “A Woman with a Screen-Printed Headscarf Called Habari.” Accessed September 1, 2024. https://syrian-heritage.org/a-woman-with-a-screen-printed-headscarf-called-habari/.

Syrian Heritage. “The Ink That Lasts Forever: Textile Printing in Syria.” Accessed September 1, 2024. https://syrian-heritage.org/the-ink-that-lasts-forever-textile-printing-in-syria/.

Topçuoğlu, Oya. Iconography of Protoliterate Seals. na, 2010.

Zoghbi, Pascal. ‘First Printing Press in the Middle East’. 29LT (blog), 2012. https://blog.29lt.com/2010/06/16/1st-printing-press-in-me/.

[1] Rafa Nasiri, 50 Years of Printmaking (Milano: Skira, 2013).

[2] Rafa Nasiri, 50 Years of Printmaking (Milano: Skira, 2013).

[3] Sonja Mejcher-Atassi, “Unfolding Narratives from Iraq: Rafa Nasiri Book Art”; Rafa Nasiri, Artist Books (Milano: Skira, 2016), 47.

[4] Nasiri p90; Dia al-Azzawi, “Graphic Design and the Visual Arts in Iraq,” in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, ed. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah A. Rogers, and Nada M. Shabout (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 370-371; Zeina Maasri, Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut's Global Sixties, vol. 13 (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 200; Bahia Shehab and Haytham Nawar, A History of Arab Graphic Design (American University in Cairo Press, 2020), 83.

[5] Nasiri, 50 Years of Printmaking, 29.

[6] Ibrahimi collection - https://www.instagram.com/p/C2FaDXrPH0-/?hl=en&img_index=1

[7] Nasiri p39; al-Azzawi, “Graphic Design and the Visual Arts in Iraq”; Maasri, Cosmopolitan Radicalism, 200; Shehab and Nawar, A History of Arab Graphic Design, 83; Rafa al Nasiri his life and art; Sabah al Nasiri, May Muzaffar

[8] Smitshuijzen AbiFarès, “Experiments in Modern Arabic Typography”, 302; Nada M. Shabout, Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2007), 132.

[9] Mejcher-Atassi, “Unfolding Narratives from Iraq”; Nasiri, “Artist Books”, 126.

[10] Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFarès, “Experiments in Modern Arabic Typography,” in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, ed. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah A. Rogers, and Nada M. Shabout (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 302-303.

[11] Jamil Hammoud Molaeb, Artists and Art Education in Time of War: Lebanon (PhD diss., The Ohio State University, 1989); Halim Jurdak, https://galeriejaninerubeiz.com/storage/artists/November2018/1fk1ylAmN07Efpn6RdTE.pdf

[12] Zeina Maasri, “The Visual Economy of ‘Precious Books’: Publishing, Modern Art, and the Design of Arabic Books,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 40, no. 1 (2020): 95–113, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/755625.

[13] Maasri, Cosmopolitan Radicalism, 179.

[14] Maasri, Cosmopolitan Radicalism, 179.

He gave it to us? or is it linked from somewhere

@[email protected] given to us

needs link, reformat into footnote style

@boushra - no link, was given to us

we can give the Youtube link

Comments on The History of Printmaking Across the Arab World: Part 2