Last updated on Thu 23 November, 2017

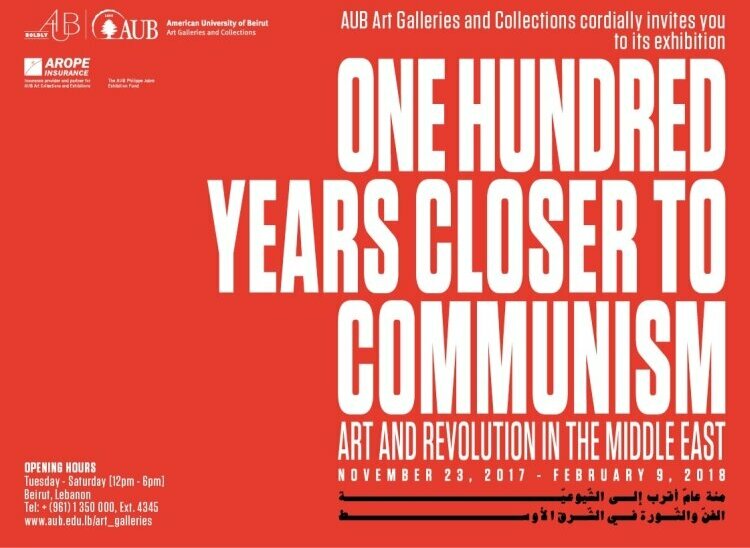

One Hundred Years Closer to Communism: Art and Revolution in the Middle East

AUB Art Galleries and Collections invites you to its exhibition "One Hundred Years Closer to Communism: Art and Revolution in the Middle East"

Nov. 23 - Feb. 9

AUB Byblos Bank Art Gallery, Ada Dodge Hall

Kamel Al Moghani (Palestine), Oussama Baalbaki (Lebanon), Serwan Baran (Iraq), Jean Chamoun (Lebanon), Yasser Dweik Palestine), Michel Elmir (Lebanon), Aref El Rayess (Lebanon), Moustapha Farroukh (Lebanon), Christian Ghazi (Lebanon), Ahmad Ghossein (Lebanon), Paul Guiragossian (Lebanon), Marwan Hamdan (Lebanon), Sheikh Imam (Egypt), Nazem Irani (Syria), Adham Ismail (Syria), Naim Ismail (Syria), Mahmoud Moussa (Egypt), Nabil Nahhas (Lebanon), Mary Jirmanus Saba (Lebanon/Palestine), Urok Shirhan (Iraq), Jonathan Takahashi (USA), Andy Warhol (USA)

This exhibition and series of events are prompted by this year’s 100th anniversary of the October Revolution. When the Bolsheviks took power in Petrograd, it sent waves of hope and fear across the entire planet. This moment of historical rupture not only determined a direction for various subsequent political struggles and movements, but had also a profound impact on cultural and artistic forms, and on the relation between radical artistic and political gesture. Even though the impact of the 1917 revolution on political and artistic life in the Middle East was not as immediate as in other regions of the world, or perceived with as much urgency, its reverberations are nevertheless discernable. The main cause proclaimed by Red October – the abolition of class exploitation and of social and national oppression – not only lay at the heart of the programs of local communist parties but it also revealed itself in the content and form of various artistic genres and media: from theater to literature, and from graphic political posters to the fine arts and cinema.

Left wing emancipatory ideas, from anarchism to socialism, emerged in the Eastern Mediterranean industrial centers of Beirut, Cairo and Alexandria before Red October. The new development of capitalist relations of production in this region brought many social contradictions and pressures to the surface, seeking political and symbolic resolution in various forms: from strikes and riots to political pamphlets and popular theater. In 1909, for instance, a theatrical play commemorating the activities of the Spanish anarchist and socialist educator Francisco Ferrer (1859-1909) was produced in Beirut. The Ferrer play did not merely stage the execution of the socialist Spaniard, but also provided an occasion to introduce to the general public the ideas of socialism and communism. In the meanwhile, theater was emerging as a new political space where nahda literati and audiences engaged (in a Brechtian moment) in discussions of the idea of universal freedom and justice, to the horror of the local colonial elites and Maronite clergy.1

One Hundred Years Closer to Communism does not seek to present an all-encompassing overview of the relation between art and communist ideas and ideals in the Middle East, nor does it simply aim to how the impact of Red October on regional art and politics. In the case of Lebanon, for instance, most of the material researched has revealed that one cannot identify a unique hegemonic voice, or arrange the relevant artistic and political production in accordance with the aesthetic or political codes of other historic contexts (for example Socialist Realism, or Communist or Fascist aesthetics and politics).2 Most of the material (from artifacts to texts and audio-visual production) is more an commingling of aesthetic, artistic, political, social-symbolic, sectarian, economic, ideological motives and perceptions that all thread together into complex visual codes and languages. In navigating amidst an intricate political context and history (from the Arab socialist revolutions of the 1950s and 1960s to the Palestinian struggle, and more recently to the Arab Spring) we have worked to keep our focus on the relation between art and revolution—with the term “revolution” here understood in its Marxian formulation as class struggle and emancipation from capitalist exploitation.

This exhibition is an attempt to construct a situation, or perhaps an intervention in the cultural status quo, rather than to provide a survey of various forms of politicized artistic practices. In producing it we were driven by certain prevailing concerns: how, for instance, to apply a dialectical approach to cultural and political activities (the relationship, for example, between detached artistic practice and engaged political struggle) within the format of an art exhibition; or how to look back at revolutionary exhibition design practices without falling prey to the current general trend of uncritical, glorifying appropriation, re-staging or re-enactment (an objectification twice over).

One Hundred Years Closer to Communism is not a celebratory exhibition. There is nothing to celebrate today. The exhibition does not seek to merely illustrate the relation between art and communist politics in the Middle East but to problematize it. Therefore, we included not only works by artists who have sincerely sought political resolution by artistic or aesthetic means, but also art that can be perceived as counterrevolutionary or driven by sentimental nostalgia and naïve utopianism; artifacts that bear witness to the closure and the death of revolutionary energy; works that for various reasons openly exploit the symbolism of class emancipation, or that may only be unconsciously suggestive of a hidden emancipatory energy; or works of art and initiatives that deploy the commodified attributes and symbols of Red October (Che Guevara and the AK-47) as markers of distinct lifestyles or themes of consumption. We also show objects that have not been produced in the Middle East but merely consumed here in local private collections. This exhibition is more like a rite in which we hope that, by putting together artifacts, archival material, posters, prints, photos, film, theater, and communist fetishes from different periods and styles, we will be able to call on, or even communicate with, the ghost of Communism.

We are thankful to the many people who assisted us in launching this project, as well as to those who did not. To the former, we are grateful for offering or helping us find valuable research material, and to the latter, we are grateful for reminding us of enduring contradictions and obstacles, and of how arduous the road remains to a better and more just world.

Octavian Esanu AUB Art Galleries

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art