Written by Wafa Roz Mohamad Naghi was born in 1888 in Alexandria, Egypt, into a well-connected family. His father, Musa Naghi Bey, was a landlord of Iraqi and Kurdish ancestry who worked as the...

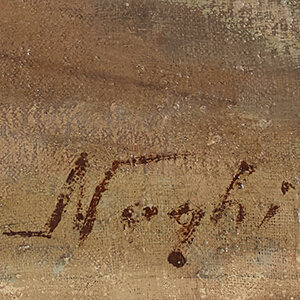

MOHAMED NAGHI, Egypt (1888 - 1956)

Bio

Written by Wafa Roz

Mohamad Naghi was born in 1888 in Alexandria, Egypt, into a well-connected family. His father, Musa Naghi Bey, was a landlord of Iraqi and Kurdish ancestry who worked as the director of customs in Alexandria. Naghi's maternal grandfather, Rashid Kamal Pasha, was governor of Sudan and the Red Sea Coastal area and the commander-in-chief of the Sudanese army at the Ethiopian border. Mohammad completed his secondary education at the elite Swiss School in Alexandria, and then went on to study law at the University of Lyon in France from 1906-1910. He studied at the Scuola Libera del Nudo at the Academy of Florence until 1914, where he was the institution’s first Egyptian student.

Naghi was also the first Egyptian to head the School of Fine Arts in Cairo, which he did from 1937 to 1939. Cairo’s first arts college, the school was founded by Prince Yusuf Kamal in 1908 and had been directed only by Italian and French artists before Naghi took the helm. In 1939, Naghi was appointed the director of the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art, a position he held until 1947. Then, he was appointed to the Egyptian Academy in Rome, where he stayed until 1950 while serving as a cultural attaché to Italy. In 1952, he established and directed the Cairo Atelier art gallery.

Naghi was a refined cosmopolitan. He grew up in the multicultural milieu of Alexandria, long a crossroads between Europe, Asia, and Africa. In school, he befriended Italian modernist poet, Giuseppe Ungaretti, and the futurist theoretician, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and studied under the mentorship of Italian artist Alberto Piattole. He learned about the Renaissance masters in Florence, where he painted nudes, landscapes, and Roman ruins in oil paintings such as The House of Faun in Pompeii (1912). Naghi was a member of “Al-Ruwwad,” or “the pioneers,” as the first generation of Egyptian modern artists is known. During the Nahda, or Arab renaissance, these talented young men trained under the tutelage of European artists, learning Western genres and techniques. Naghi’s European training and elite background, along with the political developments in Egypt, shaped much of his art and fashioned his role as a diplomat and cultural educator.

Following WWI, Naghi moved to France for a year, where he met master impressionist Claude Monet at his home in Giverny. Under Monet’s guidance, Naghi developed an impressionist style in his early works, as can be seen in Al-Mahmal, an oil painting from the period. Here, Naghi captures a fleeting moment in time: a crowd gathers to watch al-mahmal, a ceremonial palanquin containing the kiswa of the Ka’aba, parade through the streets of Cairo on camelback. Traditionally, this procession took place yearly, as it carried the kiswa from its place of manufacture in Egypt to Mecca for the annual pilgrimage. In Naghi’s painting, peasants and children surround the golden yellow mahmal as military personnel on horseback keep them at a distance. Naghi’s rapid, loosened brushstrokes, broken into colorful dabs of blue, pink, yellow, green, and brown, translate the rush of this grandiose ceremony.

Mohammed Naghi was taken with the national zeal of the 1919 Egyptian revolution against British rule, supporting the foundation of a constitutional monarchy in 1923. Swept up in the spirit of independence that animated the Nahda era, Naghi and his peers in Al-Ruwwad pushed for the development of nationalist art based on folklore and Egyptian cultural heritage. In 1922, the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamen by British Egyptologist Howard Carter stoked worldwide Egyptomania, giving Egyptian artists yet more impetus to celebrate their culture’s glorious past. They did this in a “neo-pharaonic style,” reformulating ancient Egyptian iconography using Western formulas of representation. In this context, Naghi produced Egypt’s Renaissance or The Cortege of Isis (1920 -1922), a government-commissioned mural painting for the inauguration of the parliament building in Cairo. It was installed in the Senates Council Chamber, or Maglis Al -Shuyukh. In a well-balanced horizontal composition dominated by a green ochre palette, the painting features Isis, the ancient Egyptian goddess of fertility and maternity, leading a lengthy procession. The march includes people from all walks of life –peasants, scholars, musicians, Islamic religious figures, and worshipers with sacrificial offerings– who follow Isis as she paves the way from Egypt’s storied past into its modern present. Patriotic in content and theatrical in form, the large-scale painting reminds the viewer equally of Mexican murals and the ancient Egyptian frescoes of the Theban Valley.

Naghi’s passion for pharaonic past predated the 1919 revolution. In 1911, he kindled his curiosity during a visit to Old Gourna in Luxor with Sheikh Ali Abdel Rasoul, a local who had excavated ancient tombs in the Theban Necropolis. Thirty years later, when establishing a Luxor artist’s residency, he would choose Gourna as its site. In 1937, Naghi’s love of his country’s antiquities led him to become the first director to introduce the study of ancient Egyptian art into the curriculum of the School of Fine Arts in Cairo. As The Cortege of Isis suggests, his interest in the era of the pharaohs was deeply connected to contemporary patriotism, which shone through in his commitment to bringing art to the Egyptian people. His writings promoted public art by state-assigned Egyptian artists, and from 1934 to 1939, he himself produced a series of five large scale paintings to adorn Al-Mu’asa Hospital in Alexandria. One of these paintings, Medicine in the Arab World, broadened his focus from the glories of Egyptian history to the accomplishments of the whole Arab world through the ages.

Aided by his family's stature, Naghi became a diplomat and cultural attaché during the interwar years, traveling to Rio de Janeiro, Paris, Prague, Adis Ababa, and Rome. In Paris, he befriended the French painter Andre Lhote, who introduced him to fauvism and cubism. In the early 1930s, as cultural attaché to Ethiopia, Naghi produced his most prolific body of work, known as his “Abyssinian period.” Applying bright and warm colors in an expressive style, he produced figurative paintings depicting daily life and rituals such as in Religious Procession, Addis Ababa (1932). During this time, Naghi expressed his support for independence movements and the freedom of indigenous people, and produced several portraits of Emperor Haile Selassie, whose coronation in 1930 ushered in an era of reforms that shaped the course of modern Ethiopian history. In Maydan Addis Ababa Menelik II (1932), he painted the square dedicated to Emperor Menelik II in Addis Ababa, including his equestrian sculpture, in honor of the founder of the Ethiopian state. Similarly, besides the colorful landscapes that Naghi produced in Cyprus, the homeland of his Greek-Cypriote wife, he painted the portrait of the Archbishop Makarios who fought for the liberty of Cyprus against the British.

The peasant, al-fellah, is a recurrent theme in Naghi’s oeuvre. During his frequent visits to his family’s country estate in Abu-Hummus, Naghi painted the landscapes and popular culture of rural Egypt, heavily featuring Egyptian peasant-farmers as elements of the region’s “timeless” beauty. For example, The Village (1928) portrays an idyllic image of rural life, centering al- fellah as the apparent guard of a homogenous and authentic culture. The painting is not completely unrealistic, however, as it also reflects the stratified class structure between peasant and landlord. Naghi sets his family members apart from the farmers and domestic workers through dress and posture; Naghi’s father wears a black, Western-style suit, and is sitting on a chair, while peasants in galabiyyas stand or squat on the floor. The calm and earthy palette of The Village is inspired by the agrarian environment, and can be seen in many of his other paintings of rural people. Works such as The Peasant and the Bean Flower (1932), a profile portrait of a young fellaha dressed in pale blue, reflect the untroubled vision of countryside Egypt.

While the artist experimented with watercolor, ink, and pastel on paper, Naghi’s most ambitious work was largely done in oil paint. One such monumental painting is his School of Alexandria (1939-1952), which celebrates Egypt’s contribution to human civilization by alluding to a giant of the Italian renaissance. Raphael’s famous School of Athens (1509-1511), a fresco located in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, illustrates a congregation of great philosophers from different eras of Western civilization, some of whom bear the faces of the artist and his contemporaries (e.g. Da Vinci and Michelangelo). The School of Alexandria, measuring 700cmx300cm, is a large-scale horizontal canvas carefully covered in a pastel-toned composition of ancient and contemporary intellectuals. As in the School of Athens, they are depicted in conversation, gathering to learn from one another by the Mediterranean Sea. They stand in the shadow of Ptolemaic temples and an equestrian statue of Alexander the Great, founder of Alexandria. In the middle, Archimedes is shown handing his inventions to Ibn Rushd. Around them, Naghi groups other European and Egyptian scholars on both sides of the painting, such as the Islamic reformer Muhammad Abduh, the sculptor Mahmud Mukhtar, the liberal intellectual Lutfi al-Sayyid, and the writer Taha Husain. This group stands atop a decorative floor reminiscent of Western renaissance ceiling frescoes, such as Michelangelo’s celebrated work in the Sistine Chapel.

Naghi applied the last touches on his chef d’oeuvre at his villa in Giza in 1952, as Pan-Arab nationalism instigated yet another sea change in Egyptian history.

By the time of its completion, Naghi had worked on the School of Alexandria for more than ten years, even taking the giant canvas with him on his diplomatic travels. The artist lived to see the painting exhibited in the Egyptian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale in 1954, and it was later acquired by the Municipality of Alexandria to adorn the main reception room.

Naghi passed away in 1956, in his villa close to the Giza pyramids. Nearly a decade after his death, the Ministry of Culture, with the help and urging of his sister Effat, converted the villa into a museum. It was inaugurated on July 13, 1968.

Sources

Abaza Mona with Collector’s Notes by Sherwet Shafei, Twentieth-Century Egyptian Art, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, New York, 2011.

Fawaz, Leila Tarazi, et al. Modernity and Culture: from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. Columbia University Press, 2012.

Johnson, Amy J., et al. Re-Envisioning Egypt 1919-1952. The American University in Cairo Press, 2005.

Kane, Patrick M. The Politics of Art in Modern Egypt: Aesthetics, Ideology and Nation-Building. Verlag Nicht Ermittelbar, 2013.

Karnouk, Liliane. Modern Egyptian Art, 1910-2003. American University Press, 2005.

“Mohammed Naghi.” Barjeel Art Foundation, https://www.barjeelartfoundation.org/artist/egypt/mohammed-naghi/.

“My Bonhams.” Bonhams, https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/23907/lot/93/?category=results&length=90&page=1.

Radwan, and Nadia. “Between Diana and Isis: Egypt's ‘Renaissance’ and the Neo-Pharaonic Style (1920s‒1930s).” Collections Électroniques De L'INHA. Actes De Colloques Et Livres En Ligne De L'Institut National D'histoire De L'art, INHA, 8 Sept. 2017, https://journals.openedition.org/inha/7194.

Radwan, Nadia Lotfy. “Dal Cairo a Roma. Visual Arts and Transcultural Interactions between Egypt and Italy: Semantic Scholar.” Undefined, 1 Jan. 1970, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Dal-Cairo-a-Roma.-Visual-Arts-and-Transcultural-and-Radwan/ba271f0e89b39214281fcebdf4b8de0a445f1aee.

Secrets of the Valle of the Kings - Zahi Hawass - April 2008 - The Plateau - Official Website of Dr. Zahi Hawass, http://guardians.net/hawass/Press

Releases/secrets_of_the_valley_of_the_kings.htm.

Seggerman, Alexandra, and Fatenn Mostafa Kanafani. “Creating A New World: The Vanguard of Egyptian Modern Art.” Rawi Magazine, https://rawi-magazine.com/articles/vanguard/.

Tate. “'Religious Procession, Addis Ababa', Mohammed Naghi Bey, 1932.” Tate, 1 Jan. 1970, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/naghi-bey-religious-procession-addis-ababa-n04823.

النجار صفية. “بروفايل: محمد ناجي.. حارس الفنون الشعبية.” الوطن, 5 Apr. 2017, https://www.elwatannews.com/news/details/1975007.

“تُراثنا المُهمل- متحف ''محمد ناجي'': عُزلة في الحياة و''زيارة كل فين وفين''.” مصراوي.كوم, https://www.masrawy.com/news/news_various/details/2014/2/11/173610/ت-راثنا-الم-همل-متحف-محمد-ناجي-ع-زلة-في-الحياة-و-زيارة-كل-فين-وفين-.

CV

Exhibitions

2024

The Collector´s Eye XI, Ubuntu Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

Arab Presences: Modern Art And Decolonisation: Paris 1908-1988, Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France

2022

The Egyptian Art in the Twenties of the Last Century, Centre des Arts, Aisha Fahmy Palace, Cairo, Egypt

2021

Contemporary African Art from the permanent collection of the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, The Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts Amman, Jordan

2019

The Collector’s Eye VI, Ubuntu Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

2017

Lines of Subjectivity: Portrait and Landscape Paintings, Jordan National Gallery, Amman, Jordan

1936

Abyssinian works, the Tate Gallery, London, UK

1932

Abyssinian works, Salon in Cairo, Egypt

Awards

Golden medal award for his painting Egyptian Renaissance, 1920-1922, displayed at Paris Salon.

Collections

The Mohamed Naghi Museum, Giza, Egypt

The Effat Naghi and Saad el-Khadem Museum, Zeytoun, Cairo, Egypt

Barjeel art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, Amman, Jordan

Press

Egyptian Modern Art Essay Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History The Metropolitan Museum of Art.pdf

The Story of Ali Labib House بيت المعمار المصرى - على لبيب.pdf

Ahram Online - Solidarity on the Nile.pdf

Cairo Museums.pdf

تُراثنا المُهمل- متحف _محمد ناجي_ عُزلة في الحياة و_زيار...مصراوى.pdf

متحف محمد ناجي..فنون تحكي التاريخ وتوثق الحاضر - البيان.pdf

محمد ناجي-Dusk & Dawns.pdf

Arab art chronicles of the 20th century Arts Culture – Gulf News.pdf

الوطن منوعات بروفايل محمد ناجي.. حارس الفنون الشعبية.pdf

artistic museumes - Mohamed Nagy, Founder of Modern Egyptian....pdf

The Egyptian Academy of Art in Rome – Watani.pdf

MohammadNaghi_NajiNewspaper_7thyearDeathMmemorial_Press.PDF

محمد ناجى رائد الفن التشكيلى.pdf

Atelier Alexandria_ The persistence of the state Mada Masr.pdf

Remembering My Mother’s Alexandria - The New York Times.pdf

The Birth of Art and Liberty, Egypt_s Surrealist Art Movement Contemporary Arab, Iranian & Turkish Art Sotheby’s.pdf

محمد ناجي-Dusk & Dawns.pdf

الوطن منوعات بروفايل محمد ناجي.. حارس الفنون الشعبية.pdf

Renowned Egyptian artists Mohammed and Effat Naghi’s works to be auctioned in Paris.pdf

1Creating A New World_ The Vanguard of Egyptian Modern Art _ Rawi Magazine.pdf

1The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art By Sultan Saoud El qassimi .pdf

MOHAMED NAGHI Artwork

Become a Member

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Welcome to the Dalloul Art Foundation

Thank you for joining our community

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies