Tania Bakalian Safieddine, known as Tanbak[1], was born to Armenian parents in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1954[2]. Tanbak, a contemporary visual artist produced paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media...

TANIA 'TANBAK' BAKALIAN SAFIEDDINE, Lebanon (1954)

Bio

Written by ELSIE LABBAN

Tania Bakalian Safieddine, known as Tanbak[1], was born to Armenian parents in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1954[2]. Tanbak, a contemporary visual artist produced paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media installations to reflect on a personal and collective war-ridden state, in general. Tanbak carried the history of the Armenian Genocide, passed on from her family, using it to inform much of her artistic themes. She left Lebanon in 1971, avoiding the imminent conflict of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), ignited by religious tensions and socio-economic disparities, she relocated to the Iberian Peninsula.

Living in both Madrid and Barcelona, Tanbak took courses in Spanish Literature before moving to Washington, D.C., where she studied International Relations at Georgetown University. In 1982, she attended an art preparatory school in Paris, where she studied painting, and the Martenot Method at the École d’Art Martenot de Paris. Here, she was taught using a pedagogical approach developed by Maurice Martenot, the inventor of the Ondes Martenot, an early electronic musical instrument created in 1928. This method focuses on teaching music through the expressive capabilities of the Ondes Martenot, emphasizing emotional expression, musicality, and the physical gesture of producing sound. In art pedagogy, it is known for fostering a straightforward and accessible understanding of one’s creative process. Tanbak eventually began teaching the Martenot method to others, as well as its application in painting. She would do so for several years before returning to Beirut in 1990, as the Lebanese Civil War ended.

Irrespective of her education, Tanbak can be considered a self-taught artist, as her time spent in Spain during the liberation of art culminated in enriching and shaping her oeuvre. The 80s were marked by unrestricted cultural, social, and sexual freedom, led by Spain's creative community. Tanbak’s introduction to the work of Francisco Goya[3], the Spanish romantic painter and printmaker, inspired many of her aesthetic choices. Her encounter with Goya’s Pinturas Negras series, 1819-1823, at the Prado Museum in Madrid, exposed her to Goya’s most haunting and enigmatic works. They reflected a grim and disturbing vision of humanity and an intense emotional depth presented through their dark tones and often macabre themes. Tanbak’s fascination with Goya’s criticism of religious excess and civil conflict translated into her own work, shaping a rather pessimistic style. She could relate to Goya’s portrayal of his experiences with a tumultuous Spain – due to the Spanish Enlightenment and the Peninsular War – as she too had been impacted by war and socio-political turmoil.

As the Lebanese Civil War began to subside in 1990, Tanbak returned to Beirut and began producing art that reflected the recent dark history of her homelands – Lebanon and Armenia. Tanbak set up an atelier on Monot Street near the Beirut city center, a milieu that was at the time surrounded by destruction and infested with rats. Along with her two sons, she would frequent the dilapidated streets next to her atelier and gather ash, sand, and debris. She even collected ash from friends and families, explaining she would learn a lot from the consistency and color of the ash they provided her with. Tanbak used these materials to paint works that she displayed at Espace Sandra Daher, during her first solo exhibition in 1990. The works commemorated the many martyrs and warriors of the recently concluded civil war.

The finding of parallels between different civilizations and different historical periods is an indispensable part of understanding Tanbak’s oeuvre. In her 2001 exhibition, Peinture, Guerre, Considerations (Painting, War, Considerations), she used fragments of ash and wood to create assemblages of obscurely pieced portraits[4]. Tanbak used a dark and earthy palette, that was a stark contrast to her initial vibrant painting tutelage. Among the many works of this exhibition is the portrait, Sans identité, N.D., from the Portraits by ashes series, 1997-1998. The work epitomises Tanbak’s thematic expression of the faceless martyrs who had lost their lives at war. The significantly small 25 by 35cm wooden slab displays an indiscernible head with rough and textured finger scrapes, obscuring the identity of the figure. The earthy greys, rusty browns, and a pale, corpse-like, lilac, provide a sombre and heavy tone. Comprised of ash and paint, the rough texture of the artwork contrasts the “smooth” surroundings that we currently live in, as Tanbak expressed.

Additionally, part of the Peinture, Guerre, Considerations exhibition is the mixed media sculpture, Untitled, N.D., housed at the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF). The work is a sculpture consisting of an assemblage primarily made from junk material that is dark and earthy, aligning with Tanbak's thematic expression in her series. The piece is constructed on a tall, slender wooden pole, with the focal point being an intricately abstract, fragmented, and almost helmet-like structure composed of jagged, overlapping pieces of rusted metal and repurposed plastic. The helmet is constructed with an intertwined deep blue plastic braid and several rusted metallic sheets. The texture is rough and uneven, creating a sense of natural rawness and organic decay. The overall structure resembles a Medieval European heaume, a metal helmet worn by Crusaders, well into the 14th Century. Tanbak’s nod to this soldier attire once again reflects her fascination with war.

Tanbak continued to work on dark and primitive assemblages, integrating Spanish symbols such as the bull. The bull is seen as both a symbol of modern Spain[5] and an ancient symbol of strength and fertility[6]. Tanbak’s 2003 Toro exhibition, is made up of a series of bull-shaped sculptures, highlighting the parallels between antiquity and modernity. Her sculpture, Untitled, N.D., also part of DAF, presents an assemblage which has a central, vertical wooden pole that acts as the spine of the work, similar to her other installations from the Peinture, Guerre, Considerations exhibition. Affixed to the pole are pieces of metal, fabric, plastic, and leather, which are arranged in a somewhat chaotic, yet carefully balanced fashion, mimicking the head of a bull. Oxidized metal pieces make up the bull’s head; the pieces are jagged and irregularly shaped, also suggesting they are scraps or found objects the artist had collected and repurposed. The ‘bull-head’ sculpture has an industrial and post-apocalyptic feel, reflecting themes of recycling and transformation. It includes elements from the modern world such as plastic pipes, but also antiquated materials such as leather. Within the Toro series, other pieces included fur, which made these bullheads look like primitive ritual objects.

The relationship between contemporary, modern, and classical art is quite important for Tanbak. She notes in an interview that, “Antiquity is so modern [and] you cannot be modern if you do not have a base of antiquity behind you”. This is a phenomenon that writers like Lisa Modiano have pointed out in their observations of the primitivism of the works of Spanish modern artists like Pablo Picasso[7]. Tanbak’s work can be described as both unmistakably contemporary through her themes and subject matters, while simultaneously pre-civilizational and primitive in her forms or motifs. This can be seen in her 2009 exhibit, Habibi, Do Black Roses Exist?, which consists of a series of monochromes, a staple of modern art in which the entirety of a canvas is painted or almost completely covered in a singular sombre color[8]. Tanbak’s monochromes, however, were also covered in claw marks, as if the paintings were ravaged by a beast, as seen in the work Untitled, 2008.

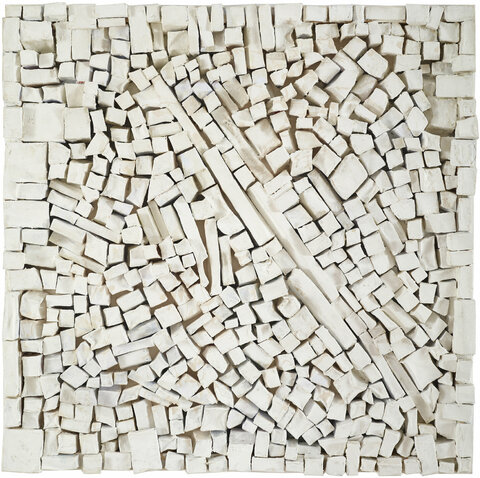

Tanbak created art that resonated with central themes that were relevant to her reality – one that was war-ridden. A central theme she consistently returned to was her Armenian heritage. Another important monochromatic work by Tanbak is her rendition of refugee camps in her mixed media on canvas, Stones, 2014, housed at DAF. The off-white monochromatic work is a highly tactile piece, with numerous small, irregularly shaped cardboard cubes that resemble stones. The cubes are arranged in a somewhat concentric pattern, highlighting the shadow and depth created by an irregular surface. Stones is another example of Tanbak’s preoccupation with historical parallels where she had the Karantina refugee camps of Lebanon in mind. The work emanates from a very personal story as Tanbak’s father had a factory in the Karantina Community next to Bourj Hammoud, in Beirut, Lebanon. He insisted she never forget the dilapidated houses of the refugee camp where they – the expulsed Armenians – used and continue to live. Tanbak’s Armenian people settled in these camps upon their arrival to Lebanon in the 1920s, fleeing the genocide in Armenia[9]. Moreover, these same camps later hosted the Palestinian refugees after escaping Israeli expansion in 1948[10]. Tanbak’s white monochromatic work is a representation of such a camp community in all its bareness and hypnotic congestion.

Tanbak has traversed an artistic journey that reflects her personal history and the collective experiences of her Armenian heritage and war-torn homelands. Her war-inspired assemblages serve as poignant reflections on the Lebanese Civil War and Armenian Genocide. Recently, however, Tanbak's focus has shifted. During the Covid-19 Pandemic, she began creating floral embroideries, showcasing a transition to themes of beauty and renewal[11]. Through her evolving artistry, Tanbak continues to reflect and redefine her connection to her past and present, embodying a journey of continuous transformation and healing. She remains an active artist in Beirut, sharing her latest creations and inspirations with a global audience.

Edited by Wafa Roz

Notes

[1] Her nickname, “Tanbak”, stems from childhood, owing to the first three letters of her name coinciding with those of tanbak – a type of tobacco used in the Arabian waterpipe known as Shisha. This moniker was further cemented as she took up cigarette smoking. Additionally, during the period leading up to the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), her nickname served a crucial protective role by obscuring her religious identity in a context where sectarian affiliations[1] could be lethal.

[2] Artsvi Bakhchinyan, “Tania Bakalian Safieddine: ‘All My Works Arise from My Armenian Identity’ - the Armenian Mirror,” The Armenian Mirror Spectator, February 26, 2021, mirrorspectator.com

[3] Florence Thireau, “Tanbak,” Mille et un Artiste, accessed January 10, 2024, florencethireau.wordpress.com

[4] Lana Captan, “Artist challenges the silence of the civil war”. The Daily Star. Nov. 11, 2001, www.dafbeirut.org/content

[5] Jessica Jones, “A Spanish Icon: The Untold Story of Spain’s Osborne Bulls,” Culture Trip, July 28, 2017, www.theculturetrip.com/eur

[6] 1. Gary L. Noffke, The Symbol of the Bull as an Art Form (Eastern Illinois University, 1966).

[7] “How Much Does Picasso Owe to African Art?,” TheCollector, October 23, 2023, www.thecollector.com

[8] Tori Campbell, “The Monochrome: A History of Simplicity,” Artland Magazine, April 13, 2023, www.magazine.artland.com/t

[9] Dakessian, Antranig. “The Armenians of Lebanon.” AGBU. Accessed January 21, 2024. agbu.org/lebanese-arme

[10] Refworld | World Directory of minorities and indigenous peoples ..., accessed January 21, 2024, www.refworld.org/docid

[11] “Tanbak’s Instagram Page,” Instagram, accessed January 10, 2024, www.instagram.com/tania_tanbak

Bibliography

Bakhchinyan, Artsvi. “Tania Bakalian Safieddine: ‘all My Works Arise from My Armenian Identity’ - the Armenian Mirror.” The Armenian Mirror Spectator, February 26, 2021. www.mirrorspectator.com

Caione, Anna. The Martenot Pedagogy: The Link Between Gesture, Artistic Expression and State of Mind. Italian Services Institute, 2016.

Campbell, Tori. “The Monochrome: A History of Simplicity.” Artland Magazine, April 13, 2023. www.magazine.artland.com

Dakessian, Antranig. “The Armenians of Lebanon.” AGBU. Accessed January 21, 2024. https://agbu.org/lebanese-armenians/armenians-lebanon.

“How Much Does Picasso Owe to African Art?” TheCollector, October 23, 2023. www.thecollector.com

Jones, Jessica. “A Spanish Icon: The Untold Story of Spain’s Osborne Bulls.” Culture Trip, July 28, 2017. www.theculturetrip.com/eur

Khodr, Zeina. “Lebanon’s Identity Crisis.” Al Jazeera, June 4, 2012. www.aljazeera.com/feat

Noffke, Gary L. The symbol of the Bull as an art form. Eastern Illinois University, 1966.

Refworld | World Directory of minorities and indigenous peoples ... Accessed January 21, 2024. www.refworld.org/docid

Shisha | definition in the Cambridge english dictionary. Accessed January 19, 2024. www.dictionary.cambridge.org

Sibai, Liam. Interview with Tania “Tanbak” Bakalian Safeieddine. Other. The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, n.d.

“Tanbak’s Instagram Page.” Instagram. Accessed January 10, 2024. www.instagram.com

Thireau, Florence. “Tanbak.” Mille et un Artiste. Accessed January 10, 2024. www.florencethireau.wordpress.com

تعريف و شرح و معنى اقتحام بالعربي في معاجم اللغة العربية معجم المعاني ... Accessed January 19, 2024. www.almaany.com/ar/

CV

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2014

In Transit, Agial Art Gallery, Beirut, Lebanon

Voracious Urbanity, Agial Art Gallery, Beirut, Lebanon

2009

Habibi Do Black Roses Exist?, Agial Art Gallery, Beirut, Lebanon

2007

Darwin Project, Beirut, Lebanon

2003

Torro, Agial Art Gallery, Beirut, Lebanon

2001

Peinture, Guerre, Considerations exhibition

1990

Espace SD, Beirut, Lebanon

Selecred Group Exhibitions

2016

Yalla Dada, Station Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

2014

Thin Skin, Taymour Grahne Gallery, New York, United States of America

2003

Salon d'Automne, Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock Museum, Beirut, Lebanon

2000

Salon d'Automne, Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock Museum, Beirut, Lebanon

1998

Salon d'Automne, Nicolas Ibrahim Surcsock Museum, Beirut, Lebanon

Public Exhibitions

2006

Tinzakar Ma Tinaad, Beirut Lebanon

Collections

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

Saradar Group, Beirut, Lebanon

The Abraham Karabajakian Collection, Beirut, Lebanon

Press

Confessions en temps de Corona: Tania Tanbak

Agenda Culturel, French, 2020

Atelier de peintre - Une porte ouverte sur l'art et ses questionnaires Tania Safieddine veut communiquer sa passion(photos)

Maya Ghandour

L'Orient Le Jour, French, 2000

Artist challenges the silence of the civil war

Lana Captan

The Daily Star, English, 2001

Coming back to the beginnings of time through art

Florence Thireau

The Daily Star, English, 2009

In Transit' Exhibition by Tanbak at Agial Art Gallery

Beirut.com, English, 2014

La Libanaise Tanbak s’expose à l’Agial Art Gallery

Agenda Culturel, French, 2014

Tanbak and the monochrome of mass tragedy

Jim Quilty

The Daily Star, English, 2014

Tanbak "en transit"

Colette Khalaf

L'Orient Le Jour, French, 2014

TANIA 'TANBAK' BAKALIAN SAFIEDDINE Artwork

Become a Member

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Welcome to the Dalloul Art Foundation

Thank you for joining our community

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

_Tanbak_Side2.jpg)