While settling in their colonized countries, the European powers understood that they needed to give their presence a legitimacy in the eyes of their occupied populations. They justified their actions with the ideology of colonialism, pretending to have been given a civilizing mission. The latter mission aimed to restructure the countries by applying a Western administrative, social, and economic system.

In the first half of the 20th century, the development of the arts and culture in the MENA region exemplified the process through which colonialism took shape. The Western world was the example to follow. The occupied people effectively felt that their civilizations were backward and that they were lucky to receive anything new coming from Europe. Amongst these novelties, the introduction of the oil painting on canvas – mostly presented by European Orientalist artists – was stamped by many studies as the beginning of the artistic modernity in the Arab countries1. Moreover, this marked a moment when the Europeans separated the different statuses of the ‘artist’ and the ‘artisan’. There was the objective to assimilate the indigenous into the Western civilization by disconnecting them from their social codes, values, and by extension, their identities.

Hence, the colonial authorities quickly found the interest of investing in art education. The latter served the colonialist strategy, being part of the above-mentioned European civilizing mission. In general, the colonial educational system had always been used as a softer way to assimilate the local populations, rather than violence as French sociologist René Maunier (1887-1951) confirmed: “Coloniser, organiser et exploiter ne suffit pas: ce qu’il faut, c’est surtout civiliser et éduquer; c’est franciser les indigènes, libéralement et humainement (…)”2.

Figure 1 Abdul Qadir al Rassam, View of Dijla, 1326 (1908).

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

The early artistic production labelled ‘modern’ – i.e. not traditional Arab-Islamic art –, demonstrated a compelling trend for European academism through the depiction of landscapes, as portrayed in View of Dijla (1908) (fig.1) by Iraqi painter Abdul Qadir al Rassam (1882-1952). Nonetheless, the local artists increasingly understood that they could not relate to a foreign culture and adhere to its mentality, which was imposed on them especially after having been educated in Europe. Modern Arab artists would thus (re)invent their own process of creation with their own cultural references in their artworks, embodying the national emancipation of the Arab people.

The Westernization of the Local Artistic Milieu

In the 1920s and 1930s, capital cities like Cairo, Algiers, and Beirut were very cosmopolitan. There, the new coming European communities imported their habits, leisure, and even education. A certain Western art de vivre spread across the cities and was adopted by the members of the local social elite. Yet, it has been criticized that this elite was more imitating these European habits than adhering to them in order to feel ‘modern’. For example, they would attend art exhibitions with no appreciation and knowledge for art. Sometimes, they ridiculously demonstrated a lack of taste, as Jewad Selim (1919-1961) mocked a bourgeois Iraqi interior: “Now if the taste is slightly elevated, and the head of the house feels the need for some art, then the walls will have a calendar by the Cadillac company, adorned with a photograph of a girl who does not seem to have any connection to planet Earth (…)”3.

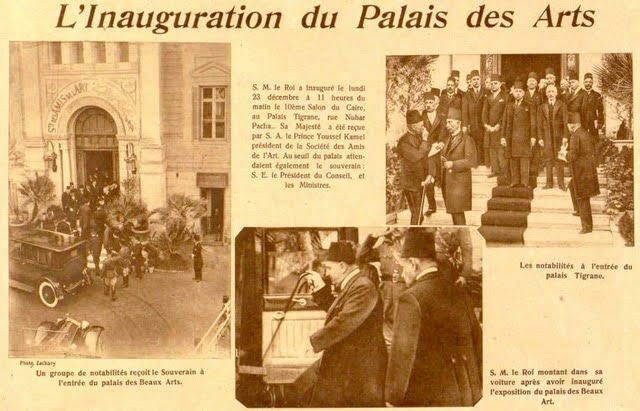

For a long time, Arab populations had looked up to the Western world, and connected the phenomenon of modernization with westernization. Modernization was viewed more precisely as a synonym of positive progress which led to perfectionism for the good of humanity4. This perfectionism was visible in artistic production and the elaboration of culture as Dr. Nada Shabout argued: “The East was overwhelmed by what the West had to offer in the arts”5. Inspired by the European model, annual salons such as the famous Salon du Caire (fig.2) as well as associations of artists and art lovers – including the Egyptian Société des Amis de l’Art (Jama’at Muhibi al-Funun al-Jamila) in 1922 and Iraqi Friends of Art Society (Jama’at Asdiqa al-Fann) in 1939 – mushroomed, and stimulated the artistic activity which had been faltering for a while.

King Fuad I at the inauguration of the Salon du Caire at Palais Tigrane, known as the Palais des

Arts, with Prince Youssef Kamal, Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil. Images, no.15, 29 January 1929.

ã Reproduction from Fatenn Mostafa-Kanafani, Modern Art in Egypt: Identity and Independence (1850-1936), p.54.

In parallel, museums like the Musée Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Algiers opened in 1930 and the Musée d’Art Moderne in Cairo a year later. Nevertheless, the historical and cultural narrative that those institutions presented was problematic. Although they were ‘national’, they were paradoxically detached from a national narrative to which the native populations themselves could relate. The first example actually celebrated the centennial of French occupation in Algeria, while the second one had the initial objective of familiarizing the Egyptian public as well as students to European art6. Lastly, both museums housed a more important collection of European artworks like Orientalist paintings rather than artworks by native artists. At that time, the royal rulers gave their countries a modern image, simultaneously pleasing the European powers of which they were often the puppets. Later on, they started providing governmental scholarships to indigenous students to complete their studies in Europe. The early modern artistic milieu in the Arab countries thus reinforced the European colonialist hegemony, both regionally and globally.

Establishing Art Education: A Form of Colonialism

In colonialism, assimilation goes hand-in-hand with the principle of imitation. The latter is effectively at the core of the relationship between the dominant and the dominated. The superiority of Western art and culture stems particularly from the idea that the dominant force (European) is the one that is able to create. Whereas, the dominated (colonized people) can only imitate as they are supposedly inferior 7. Europeans did acknowledge that there is a difference between their vision and the one of the Arab populations. However, they imposed their own as a norm: “He [the Arab] is indifferent to the shapes and colors that would provoke emotion from the rest of us… How is his perception so different from ours?... The Arab soul no longer belongs to our race” 8.

In the 20th century Arab world, colonial art education aimed to enforce Western supremacy, which was present in national art schools. The administrative organization and the training of students were modeled after the European system. The establishments similarly developed, opening one after the other 9. They were directed by European artists like French sculptor Guillaume Laplagne (1870-1927) at the École Égyptienne des Beaux-Arts (Madrasat al-Funun al-Jamila al-Misriyya) in 1908, or French painter Léon Cauvy (1874-1933) at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Algiers. Needless to say, the teachers usually came from Europe to conduct courses which were also based on the European curriculum and offered very academic teaching. The students – either foreigners or natives – trained in oil painting while experimenting genres such as nude, architecture, and sculpture (fig.3).

The room for the mould at the École des Beaux-Arts in Algiers (Rue des Consuls), 1935.

Source: regardscroisesesbaa.wixsite.com

The Islamic artistic practice did not really respond to the ambitions of the Europeans in their project of making Arab countries modern nations 10, but were not completely denied either. The Western-modeled education was conceived as a mandatory step for native art students to be recognized as ‘artists’. This educational policy reveals that these students were not able to independently produce their own art, as director Guillaume Laplagne (1870-1927) wrote about the Egyptian students in a report made in 1911. To him, the latter did not have a natural predisposition for figurative painting and sculpting – as they did not inherit this from their ancestors 11. In French Algeria, the students were trained to prepare for the entrance examinations at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris which was the ultimate challenge. Consequently, to be able to produce a national Egyptian art, Arab art practitioners had to first master European academic art.

Art Schools: A Ground for Emancipation

"Il va sans dire que l’enseignement devrait s’appliquer au style purement arabe, à l’exclusion de tout style occidental. (…) La façon, le côté manuel de la production, doit être enseigné par des artisans indigènes" 12

Ahmad Zaki Pasha (1867-1934), 1913

Progressively, the art schools took a different direction corresponding to a time when European occupation was more contested, especially during World War II. The latter international conflict effectively affected the aura of the Western countries, which were no more seen as untouchable as they pretended to be. Hence, the national emancipation that the colonized Arab population were aspiring to, also impacted education. The process of localization emerged, and was applied in art schools across the Arab world, starting with their managements. For the first time, native artists were appointed to high positions, replacing their foreigner predecessors like Egyptian painter Mohamed Naghi (1888-1956) who headed the newly baptized Higher School of Fine Arts (Madrassat al-Funun al-Gamila al-‘Ulya) in 1937. In North Africa, Moroccan artist Farid Belkahia (1934-2014) directed the École des Beaux-Arts in Casablanca in 1962 while Bachir Yellès (1921-) directed the École Nationale d’Architecture et des Beaux-Arts in Algiers, when Algeria became independent from France that same year.

In the period of post-independence, new management involved new disciplines. Teachers and artists understood that the Western academic model should not have the monopoly in the transmission of knowledge and practice. In 1941, Naghi contributed to the creation of a program at al-Gourna (Luxor) where graduate students could familiarize themselves with Ancient Egyptian art 13. For his part, Belkahia included the study of Islamic architecture and Moroccan craftsmanship (pottery, traditional jewelry, tapestry) in the curriculum of the École des Beaux-Arts in Casablanca. In the École Nationale d’Architecture et des Beaux-Arts (ENABA) in Algiers, the students could benefit from courses of applied arts including calligraphy, ceramics, miniature, and mosaic. The new added disciplines were meant to reconnect the artists with their cultural and historical artistic heritage. Then, they would be able to create works in which they synthesized tradition and modernity as seen in Composition (1974) (fig.4) by Moroccan painter Mohammed Chebaa (1935-2013).

Localizing art education, and more generally institutions, tended to define the national identity of each Arab country. What was considered to be ‘local traditional art’ was revived and used as a foundation for inspiration in terms of aesthetic, technique, and theory. The countries were showing the Western world that a non-Western modernity was possible as the Arab artists could produce by themselves, as creators and not just imitators.

Figure 4 Mohammed Chebaa, Composition, 1974.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

In the study of artistic modernity in the Arab world, the narrative sets a phenomenon through which the elaboration of the culture and the arts could not be achieved without the omnipresent intervention of the European settlers. Art education turned out to be a strategic choice to build the colonial project which was envisioned in the region. However, the constant efforts made to condition art students to European supremacy did not eventually succeed. On the contrary, this stimulated the emergence of local modern art movements where Arab artists would find a way to affirm their cultural and artistic specificities through their artworks by creating visual languages detached from Western academism.

Edited by Elsie Labban

Comments on Art Education in the Arab World