Attempts to Escape Drowning: Souad Abdelrasoul’s Women of the Nile

In contemporary Egyptian art, Souad Abdelrasoul stands out for her incisive exploration of women's emotional experiences. She describes her work as “attempts to escape drowning,”[1] – referring to women's constrictive societal experiences that stifle self-expression and discovery. Her deeply vulnerable figurative depictions capture women's imperceptible emotional interactions and existential struggles as they confront restrictions and cruelties. While her art transcends borders and national identities, the women she depicts remain connected through the Nile River. Abdelrasoul's surreal portrayals of bare, dark-skinned women along the Nile showcase their struggle, strength, and resilience as they navigate vulnerability and manipulation. By addressing themes like societal and religious constraints, cultural taboos, childbirth, marriage, and motherhood, she captures the transformative and often painful experiences of the female body in a masculine-dominant world. Ultimately, her work challenges fixed social constructs, inviting viewers into her complex and often melancholic emotional world.

Education and Painting the Nude/the Uncovered Body

The evolution of women's art education in Egypt has played a crucial role in shaping the artistic landscape from which Souad Abdelrasoul emerges, particularly in the context of the nude or uncovered body as a subject of artistic exploration. As an Egyptian artist, Abdelrasoul’s work emerges from a long lineage of Egyptian women artists. Modern Egyptian art developed during Egypt’s nationalist struggle for cultural and political independence from British rule (1882-1956) in the early 20th century,[2] marked by the founding of Egypt's School of Fine Arts (École Égyptienne des Beaux-Arts) by Prince Youssef Kamal (1882–1967) and headed by the French sculptor Guillaume Laplagne (1870–1927) in 1908. Initially staffed by European teachers, the school admitted only men. Women’s access to art remained limited by socioeconomic status. Early female artists were often Greek, Italian, affluent Egyptian Ottoman ruling class, or aristocratic women who received training abroad or through private tutors such as Effat Naghi (1905-1994).[3]

Access to art education for women improved in the early 1930s. Initiatives were led by feminist campaigns like the Egyptian Feminist Union under Huda Shaarawi (1879–1947). This movement tied women's emancipation to national independence, echoing the sentiments of nationalist leaders like Egyptian Jurist Qasim Amin (1863-1908), often referred to as the "liberator of women," who asserted that women's emancipation was essential for national independence.[4] By the mid-1930s, women actively participated in Egypt's modern art movements, including the Art and Liberty movement, such as Amy Nimr and Inji Efflatoun, and the Contemporary Art Group, including Gazbia Sirry and Zeinab Abdel Hamid.

In 1937, Egypt's School of Fine Arts appointed its first Egyptian director, the artist Mohammed Naghi (1888–1956). Still, women were not admitted. The first opportunity for women to study fine arts in a public institution came in 1939 with the establishment of the Higher Institute of Fine Arts for Women Teachers (al-Mahad al-Ali lil Funun al-Gamila lil Mo'alimat). In the Higher Institute of Fine Arts for Women Teachers, Egyptian women received local training from English instructors before being sent to London to continue their art studies. The first women to graduate from the Institute in the 1940s, including Gazbia Sirry (1925–2021), became art teachers and significantly advanced women's participation in the arts before the 1952 revolution in Egypt. Led by General Gamal Abdel Nasser, the 1952 revolution overthrew King Farouk. It established a new socialist Arab republic, implementing nationalization and promoting Pan-Arab and socialist policies, seeking to move towards greater Arab political, economic, and social cooperation.

Under President Nasser, women were admitted to the Institute of Fine Arts in Cairo and the Institute of Fine Arts in Alexandria, joining their male peers in shaping the nation’s artistic landscape,[5] and in 1956, they gained the right to vote. During this period, women gained access to live drawing classes and nude models—resources their male counterparts had previously utilized as essential to their art education. This access enabled women to master the representation of the human figure and paved the way for showcasing nude paintings.

Although women had access to fine arts education, following Nasser’s 1952 revolution, national support for feminist initiatives declined, and organizations like the Egyptian Feminist Union were dismantled as the post-revolutionary government focused on centralizing authority and promoting national unity at the expense of individual rights, marginalizing autonomous feminist organizations in favor of state-sponsored and controlled feminist initiatives.[6]

After the death of Nasser in 1970, Anwar al Sadat became president. The shift away from the socialist policies of the Nasserist regime towards Sadat's capitalist liberal economic policies led to increased unemployment and the decline of working women's economic conditions as the public sector shrunk drastically.[7] Furthermore, conservative values were augmented as the government set an alliance with the Muslim fundamentalists. For instance, in the 1971 Constitution, article 11 ensures gender equality, 'without violation of the rules of Islamic jurisprudence'.

Still, during his rule, Sadat's government advocated for state feminism- improving women's political rights.[8] Sadat reformed women's personal law status, increased the number of seats for women in parliament, and allocated 10-20 percent of government positions exclusively for women. Furthermore, in 1979, Sadat's government issued the Personal Status Law, which improved women's marriage, divorce, and child custody rights and established the National Council for Women. However, it is important to note also that Sadat's government hindered activities of independent civil society feminist groups such as women's rights NGOs with the development of an infrastructure for surveillance and the restriction of funding to organizations that were not aligned with his government[9].

At the same time, Sadat's attempts to appease Islamist groups made room for a resurgence of deeply conservative views on women's roles in society. During this period, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt took advantage of the economic upheaval, resulting in social unrest caused by Sadat's governance, which focused on economic liberalization and closer ties to the West. This reached a head in 1980 after Sadat normalized relations with Israel, which was met with anger and protest from many Egyptians across the board, including the Muslim Brotherhood and leftist artists; they viewed it as a betrayal of Arab solidarity and the Palestinian cause.

In response, Sadat cracked down on opposition, resulting in the mass imprisonment of activists and artists in 1981, including feminist writer Nawal El-Saadawi and artist Georges Bahgoury, while also attempting to appease the Muslim Brotherhood with minor concessions.[10] These conservative concessions extended to the fine arts institutions, exemplified by increased arts and culture censorship for profanity, homosexuality, and nudity and the 1980 prohibition of nude models in state institutions under Minister of Culture Abdel Hamed Rodouan,[11] such as the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cairo University, Alexandria University, and Minia University.[12] In 1981, Sadat was assassinated by Islamist fundamentalist army officers.

The banning of nudes deprived future artists of a foundational aspect of art education and rendered the nude form both forbidden and taboo. Consequently, the 1980s created an artistic context characterized by political repression and a push against the constraints of state-sponsored art in a liberalized market, leading to new approaches influenced by global art movements such as neo-expressionism and conceptual art.

It was within this post-80s political context in Egypt that Abdelrasoul's work emerged. She was born in Shubra in 1974 to a family from South West Egypt near the Libyan border. She chose to pursue her studies in Minya in southern Egypt because she was not accepted into the University of Cairo, where her parents would have wished her to be - closer to home.

Minya, a city along the Nile, was dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood during a time of increased suppression of women through various forms of religious and conservative constraints. There, societal expectations challenged Abdelrasoul's artistic aspirations and compelled her to reconsider her place as a woman within a patriarchal society. The Muslim Brotherhood often patrolled the streets of Minya, breaking up mixed groups of students painting landscapes in public that Abdelrasoul joined and leaving her feeling unsafe at times.[13] Abdelrasoul's themes emerged from the emotional struggles she personally experienced as a woman in a conservative, male-dominated society along the Nile. The unfair restrictions placed on her and, by extension, other women in similar conditions shaped her worldview, sparking her desire to portray authentic female experiences in all their existential complexities.

Despite the prohibition of Nude art in Abdelrasoul’s education, the nude body became central to her work. Frustrated by the process of only drawing from photographs and textbooks, Abdelrasoul recognized the importance of live study and felt the restriction acutely. Undeterred, she persuaded two friends to pose for her at night in the Fine Arts Department and offered them a carton of cigarettes in exchange for their nude modeling. Eventually, one of the female models married a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, adopted a conservative lifestyle, and expressed shame about what Abdelrasoul called their "adventurous" secret life-drawing sessions.[14]

With her focus on depicting women's bodies, and as part of her final project, Abdelrasoul studied women's bathing rituals in Cairo's Mamluk bathhouses. She felt that women washed themselves there not simply for hygiene but "to wash something inner,"[15] as an act of emotional cleansing. Rejecting romanticized Orientalist portrayals, she presented unfiltered and raw depictions of women's spaces and affective emotional release. Abdelrasoul's artwork features women sitting on tiles, their bodies reflecting a sense of vulnerability – overweight, sad, and alone, they sweat under the heat of the water. Through this project, Abdelrasoul is not only portraying the inner world of generalized 'women' to move away from stereotypical notions of the female figure – these are also self depictions. In this early work, her loose brushwork, soft colors, defined contours, and atmospheric portrayal reclaim the female nude as a space of vulnerability and emotional authenticity.[16] By doing so, Abdelrasoul confronted the authoritative constraints imposed on her as a woman in an increasingly conservative society, reflecting the growing restrictions on women's roles and bodies.

Women of the Nile

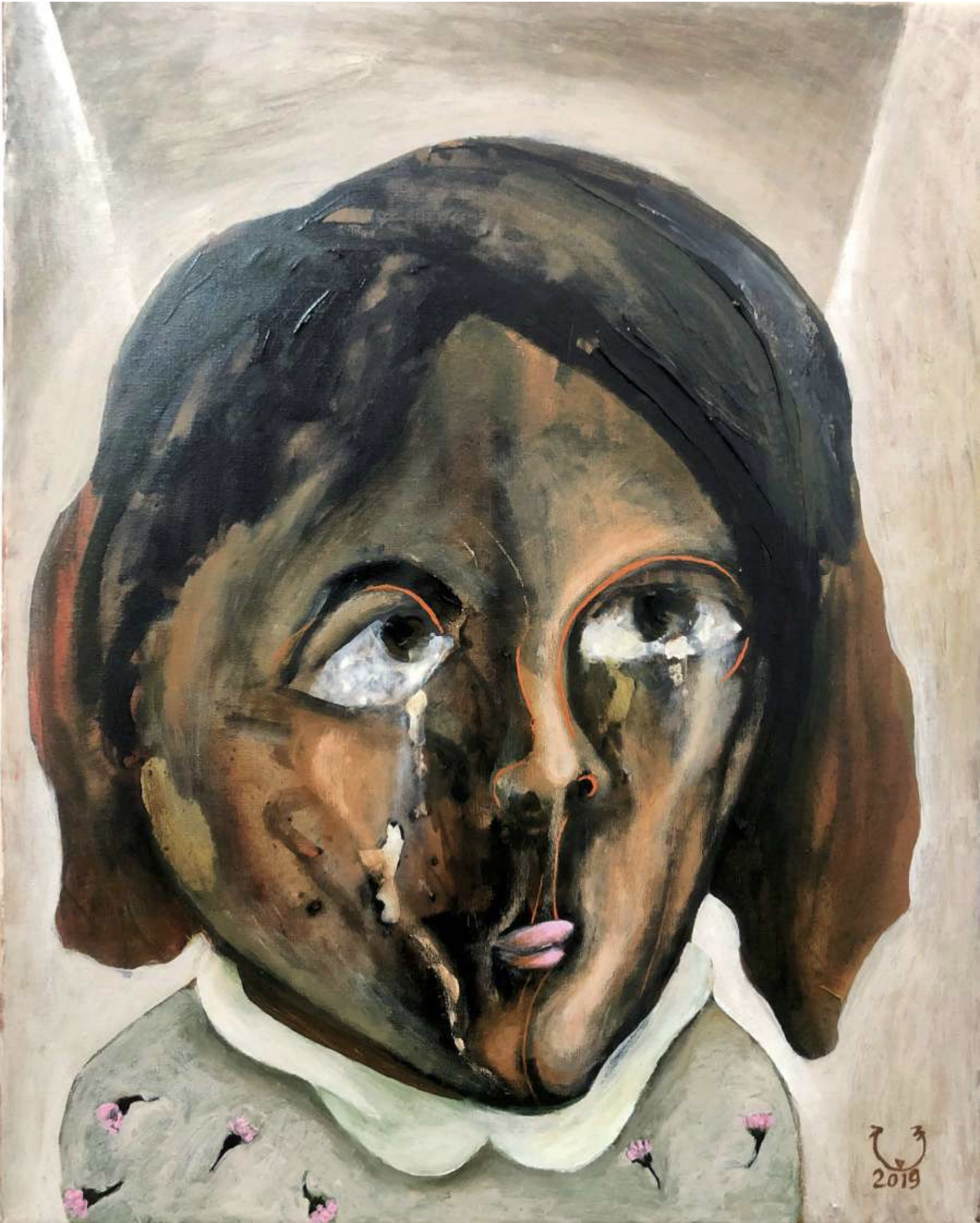

Abdelrasoul's work evolved significantly after her graduation, influenced by her travels throughout East Africa, moving beyond Egypt to reflect the longings and struggles of African women along the Nile. The artist portrays women from the Nile River region, spanning from its source in Ethiopia and Uganda to its delta in the Mediterranean Sea. This river traverses eleven African countries and serves as a vital source of life for millions living along its banks. During her travels, Abdelrasoul discovered a part of herself in the "bold, rugged beauty of African art."[17] which began to shape her art, particularly in her choice of dark skin tones and the expressive wide eyes of her subjects,[18] which are also a representation of her own eyes[19]. She emphasizes that art in Africa is ubiquitous, not confined to museums as it often is in Europe; it manifests in clothing, bodies, buildings, and especially in the eyes of the people. She describes these eyes as possessing a "freshness and rawness that strikes you—a wild beauty that compels you to stop and look.”[20]

Coming from southwestern Egypt near the Libyan border, Abdelrasoul, with her darker skin tone and distinct features, felt a more intimate connection to everyday African art than to the European art history she studied at the doctoral level. This connection enriched her artistic vision, enabling her to transcend the confines of Egyptian national identity as she collaborated with galleries across East Africa.[21] Her style evolved into more figurative surrealism, characterized by metaphorical symbols on bold, brown nude female bodies in their natural environments. She evoked raw emotion and psychological depth by incorporating distorted yet recognizable human forms with symbolic elements like animals and plants, creating introspective, dreamlike narratives that particularly explore women's emotional lives.

The colors in her artwork—deep, bold greens and blues—are directly influenced by the river, alongside the rich brown-red tones of bodies that evoke river clay. While many African artists she encounters use vibrant hues like yellows, oranges, and bright reds, Abdelrasoul's palette uniquely reflects the essence of the Nile. During this period, she adopted acrylic paint, which helped her attain the bold colors she desired. Her firm, sculptural figures feature warm clay tones, contrasting with the intense blues of the water and sky and the lush greens of the riverbanks.[22]

In Crossing the River, the artist depicts a fair skinned woman with a distorted face, with a pair of noses and mouths. She wades waist-deep in the water, carrying a green potted plant with its roots clinging to her bare skin. The roots hold on to the woman in a strained position while the flower heads stretch towards the upper right corner of the canvas finding a way out.

Other works depict women struggling for survival, like in Collective Survival, 2022-23, where seven naked women that take on the artist's likeness precariously balance on a log in the river, clinging to one another. Their bodies warp and merge, and their glazed, fearful eyes gaze toward the viewer. Watching over them is a crow – an ancient Egyptian symbol of death and rebirth, giving a sense of existential struggle. Through her profoundly symbolic and emotionally charged depictions, Souad Abdelrasoul weaves a narrative that connects women to the life-giving yet turbulent force of the Nile, its flora, and its fauna. The concept of "escaping drowning" becomes a metaphor for overcoming the emotional, societal, and existential struggles that threaten to overwhelm these women. Her subjects are depicted as naked, emotional, and struggling, yet bold and deeply rooted in the earth. They embody their attempts to keep their heads above water to escape the suffocating restrictions pulling them down.[23]

The Nile symbolizes life and freedom in her artwork, serving as a backdrop for the women in her paintings to "escape drowning." While the river is beautiful and life-giving, enabling cycles of regeneration and cleansing, it is also a powerful, raging force. Similarly, the plants unfurling gently across the bodies of women represent seemingly harmless restrictions, but these plants are just as capable of effectively strangling a tree and killing it[24].

The Vulnerable Strength of Womanhood

In her 2024 filmed Interview by Al Massart Foundation, Abdelrasoul reveals, "I love trees and their severed branches; they resemble me a lot. Something laid bare got hurt and adapted, but it has lost some dignity and remains exposed. No one consoles them." Abdelrasoul expresses a deep connection to nature, suggesting that, much like trees, women often bear the scars of their experiences.[25]

Souad Abdelrasoul’s art captures the paradoxical nature of womanhood, intertwining vulnerability and strength to explore the emotional and societal struggles women face in a masculine-dominant world. Her nude figures are natural, unromanticized, and unsexualized, depicted in bulky, robust forms that are warped and distorted. Through these vulnerable and bare figures, she addresses the sexual and societal hurdles that women encounter and their fears of judgment and limitation, exploring themes such as the complexities of male-female relations, the silencing of women, sexual taboos, and male aggression.

Abdelrasoul delves into the emotional struggles of living as a woman through the idea of silencing, well demonstrated in her painting Let Me Talk II, 2023. The painting shows a naked woman and a rooster seemingly passing through a fog of unresolved feelings. The artist alludes to the profound emotional struggle a woman faces while existing in a man's world—both restricted and desired.

The painting features a fair-skinned female figure draped in a soft, transparent white cloth that simultaneously exposes and protects her vulnerability. The woman's face is distorted, with a split jaw and two mouths. Although her left breast is exposed, hanging out of the cloth, her left hand instead covers one of her mouths, suggesting an act of self-censorship. She carries a black Fayoumi rooster, a native bird to the Nile region and a symbol of male pride, force, and sexuality. Here, he appears docile and subdued, reflecting a desire for a complementary, non-aggressive male presence in the woman's life. In nurturing and cradling the rooster, Abdelrasoul projects a longing for a male figure who does not silence or dominate her but rather one with whom she can have a mutual relationship without being silenced or forced to censor herself.

Intimacy between men and women is a recurring theme in Abdelrasoul’s work. Through observation and personal experiences, she identifies and interprets the complexities of human relationships: "I see feelings and emotions like cigarette smoke rising. It's not my imagination; I see the relations."[26] Her painting, The Laura Flower,2020,exemplifies this perspective. This work came from the observation of a couple visiting her home who sat together closely on the sofa. Yet Abdelrasoul perceived the husband as deeply unkind, noting a significant emotional distance between them, and as such she chose to portray them as separated and estranged. Abdelrasoul elucidated "the wife loved flowers and would always gift me flowers, and so I used a flowering plant as a separation wall between them.” [27] The artist is referencing the slender tall orchid plant that extends from the central bottom of the canvas to its top, dividing the composition in half and iterating the divide between good and evil. In the painting, the man has three eyes that look forward and watch his wife, suggesting a controlling or manipulative nature. The wife, one of the few non-nude females in Abdelrasoul’s work, wears a transparent galabaya dress that obscures her body, making her appear as an empty vessel. Her feet, hands, and body posture are turned away from him, even as her eyes meet his. This work captures a momentary interpretation of the emotional state within a male-female relationship.

Abdelrasoul's work also explores sexual taboos and fears. A powerful example is her painting, The Fear Between My Legs,2022. The work features a stocky, thick woman squatting with her legs apart, her nudity partially obscured by a transparent, cubic garment as she sits on the grass in darkness. Again, her face is distorted and fragmented, with three eyes looking away, while a yellow rabbit sits between her legs. Here, the rabbit symbolizes fear—since rabbits are known for their timid nature and can die from fright—as well as hypersexuality. The woman's sitting position mirrors the posture and shape of the rabbit, squatting with her hands turned in like paws. This duplication of form emphasizes the intertwined themes of fear and sexuality that both the rabbit and the woman embody.

For Abdelrasoul, The Fear Between My Legs is a deeply personal work that reflects societal fears surrounding virginity along with hers. She recalls her mother’s weekly warnings as she returned to Minya: “Suad, Khali balik min nafsik”[28] in Arabic, meaning Suad, take care of yourself, which indirectly emphasized the importance of preserving her virginity. In this painting, Abdelrasoul transforms her mother’s overprotectiveness into a tangible fear while redefining honor through a bare woman. For the artist, a woman’s honor lies in her self-discovery and struggle.

Moreover, Abdelrasul’s work often highlights the threat of male aggression or harassment. For instance, in Bull Eyes, 2020 , she depicts a woman fighting an aggressive bull, who knocks her backward into the Nile waters. Like many men in her paintings, the Bull has four eyes, watching her lecherously from every angle, his tongue out in hunger. The woman's dark skinned naked body mirrors the beast. She is wrapped in a transparent white garment; however it looks faceted and sharp edged like an armor. Her hair sticking out like a horn, while her distorted face turns away from the Bull in stony resistance. The afflicted women in Abdelrasoul’s works stand strong in spite of the limitations set by men in their lives. Abdelrasoul insists that “Women cannot be domesticated.”[29] In the face of threat, Abdelrasoul’s bare women appear on the verge of 'drowning.' Yet, their true strength lies in their courage to be unapologetically themselves. They demonstrate themselves as indomitable and unconquerable, inspiring and empowering the viewer.

The Social Roles of Womanhood and Their Restraints

For Abdelrasoul, traditional social roles, like parental guardianship or spousal control, ultimately shackle individuals and limit their dreams and freedom. Abdelrasoul, who is married to contemporary Sudanese artist Salah Elmur, explores how roles traditionally seen as blessings – such as marriage, motherhood, and family – can nurture yet also ‘define’or limit women "like delicate climbing plants that attach themselves to big trees appearing soft but ultimately suffocating.”[30]

Informed by the generational trauma of her mother and grandmother, who married at an early age and had to live through controlled oppressive relationships, Abdelrasoul captures the pain imposed on women in Yellow Cross,2022. The vertical composition of the painting highlights women's crucifixion-like experiences as they bear the weight of men's sins. Yellow Cross draws inspiration from French artist Paul Gauguin’s 1889 work, The Yellow Christ. Still, it presents a different narrative – in Christianity, where sin is a central idea, Jesus sacrifices himself for the sake of the sins of the world - her piece emphasizes that women collectively carry these burdens. In Yellow Cross, a golden cross rises from the deep blue waters of the Nile, where two nude women, partially intertwined, hang crucified against it. Their muscular, golden-brown bodies are defined and highlighted with blue tones that reflect the water and the sky above, partially covered by white cloth draped around their sexual parts. In the river green rushes grow along its side while a small rabbit floats on its back. It is cradling a smaller white rabbit nestled within its belly, symbolizing the transmission of generational trauma.

The two crucified women in Yellow Cross,2022 evoke memories of Abdelrasoul’s mother and grandmother, embodying "a common sad story” of female generational trauma, as put by the artist.[31] They married too young, became one of many wives, and were bound to narcissistic men who controlled and silenced them. Abdelrasoul reflects on her mother’s experience, recalling, “I always saw her crying, but she was silent. She never complained, she always accepted.”[32] Through her work, Abdelrasoul warns that women must take control of their lives. Despite her depiction of family struggles, Abdelraoul’s work did not receive encouragement from her family. As a reaction to Abdelrasoul’s bold symbolic artistic depictions, her sister told her : she ought to “troh ‘al narr" meaning ‘go to hell’ in Arabic. Furthermore, her self-centered father showed little or no interest in her talent nor her work.[33]

Despite the weight and restrictions of social roles associated with marriage, motherhood, and family, Abdelrasoul embraces her identity as a wife and mother, viewing these roles as precious and mysterious. Through her work, she reflects on the complex nature of motherhood and the desire to give freely and selflessly. She states, "Motherhood… produces something mysterious in the depths of human consciousness. This is a uniquely feminine quality – unconditional giving and absolute selflessness. Our bodies are the gateway for our children to enter this world."[34]

Her experiences as a mother influence her artwork, particularly as she navigates raising a young daughter in a conservative society. Sadly, her daughter feels embarrassed to invite friends over to a house filled with paintings depicting naked women, prompting Abdelrasoul to occasionally store artwork away for her daughter’s sake. Abdelrasoul laments, “Even though her mom is Souad, she is the daughter of the environment and society she lives in."[35]

Abdelrasoul explains, "When I sleep, and my daughter sleeps on my shoulder, I look at her and feel some emotions and thoughts about her future. This inspires me; my paintings come from within."[36] Other emotions arise from the challenges of Abdelrasoul’s marriage to Sudanese artist Salah Elmur. In exploring the intricate dynamics of female social roles, Abdelrasoul illustrates how the relationships meant to nurture can also impose constraints, reflecting the tension between personal expression and societal norms.

Abdelrasoul: On Being a Woman

Abdelrasoul’s artistic philosophy emphasizes the emotional depth and unique perspective women bring without surrendering to societal expectations or competing with men. The artist insists that she is not fighting for women's place in the world but reflects on her “history as a woman in an unjust and unfair society."[37] This experience manifests in various ways: the societal pressure from male judgment that pushes women to conform in addition to the continued devaluation of women's art in the art market.

Abdelrasoul reclaims this history in her painting, Eve’s Apple, 2021-2023, part of the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation collection, repositioning women as Goddesses. Eve’s Apple depicts a naked female figure suspended; her robust and curvy dark skinned body floats as if weightless or reclining on her side against a luminous, blue sky. One arm rests beneath her head in a gesture of quiet introspection, while the other delicately holds a red apple near her mouth – a potent symbol of temptation and reclaimed power. The divine figure is enveloped in a transparent, ethereal fabric that forms a protective barrier while fully exposing her. Thus, it simultaneously reveals and protects her form. The material’s periphery looks faceted and angular adding depth and a sense of fragility to the picture. On the lower register of the canvas is a thick, grassy riverbank with a mythical two-headed dog standing guard. Through bold, expressive brushstrokes and a harmonious interplay of warm and cool colors, Abdelrasoul evokes a sense of vulnerability, strength, and divine femininity, positioning the figure as a protector and a symbol of resilience.

For Abdelrasoul, this work symbolizes the dilemma women face: to be free from societal pressures and rules, they must reclaim the God-like power of the apple from the Garden of Eden. This power has been overshadowed by male masculinity, represented by the Adam’s Apple – a play on words referring to the physiological feature, prominent laryngeal, in a man's throat that produces his voice. By taking back the apple that Eve once gave to Adam – an act that has since restricted her – she reclaims her place as a goddess.[38] Ultimately, Abdelrasoul's work challenges traditional notions of achievement and masculinity while reclaiming the narrative of femininity as a source of strength. In Souad Abdelrasoul’s world, there is great beauty, depth, and strength in things that society considers weak and feminine, such as emotionality, pain, unconditional giving, and nurtured relationships.

Eventually, the artist emphasizes that her work is not explicitly feminist or ideological but arises from her lived experience as a woman.[39] She believes in gender-equality while maintaining that women are not similar to men. Her perspective contrasts masculinity which she believes asserts itself through grand achievements; with femininity, which finds meaning in emotional expression. This distinction, she argues, explains why men dominate areas like finance and power, which do not require conscience or emotion.[40] She believes that women artists offer a profound sense of "damir" or "conscience," along with a depth of feelings and an overflow of emotions that is rarely found in male artists.[41] For Abdelrasoul, women artists don't need to prove themselves; instead, their work emphasizes the unique contributions only women can bring to the art world.

Souad Abdelrasoul’s art captures the emotional essence of "attempts to escape drowning," a metaphor for overcoming the societal, emotional, and existential struggles that threaten to stifle women's authentic self-expression. Her art serves as both a lifeline and a mirror, reflecting her struggles and those of many women along the Nile. By inviting viewers to explore their surreal emotional worlds, Abdelrasoul celebrates the vulnerability and strength of women, urging them to embrace their authentic selves in all their fragility and power.

Works Cited:

“Getting to know Souad Abdelrassoul." Vimeo. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://vimeo.com/425458930?tu... Nudes is Bad News for Cairo Art Students." Daily News Egypt, June 1, 2008. https://www.dailynewsegypt.com... udents/. Accessed December 13, 2024

"Portrait of Egyptian Artist Soad Abdelrasoul: Creating Her Own Universe." Qantara. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://qantara.de/en/article/... Abdelrasoul: Film." Al Masart Foundation. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://www.almasartfoundation... Abdelrasoul Presentation." OH Gallery. Last modified November 19, 2024. https://www.ohgallery.net/souad-abdelrasoul-presentation

Abdelrasoul, Souad. "Souad Abdelrasoul's Surrealist Egyptian Art in London." New Arab. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://www.newarab.com/featur... Abdelrassoul - Circle Art Gallery." Circle Art Agency. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://circleartagency.com/ar... Masart Foundation. Abdelrasoul, Souad. "Biography." Accessed November 19, 2024. https://www.almasartfoundation... Shahbari, Dana Adnan. "Modernist Encounters Across Borders: May Ziadeh and Virginia Woolf." Master's thesis, American University of Beirut, 2023

Almas Art Foundation. Souad Abdelrasoul. YouTube, October 2023.

Aly, Menat. "Gender Washing Autocracies in Egypt: Drawing on the Presidency of Anwar El Sadat and Hosni Mubarak." Master's thesis, American University in Cairo, 2023. AUC Knowledge Fountain.

Amin, Sanaa. "سعاد عبد الرسو ل: حدود لأجساد افتراضية." Al Araby. Accessed November 23, 2024. https://www.alaraby.co.uk/%D8%B3%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D8%B3%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%AD%D8%AF%D9%88%D8%AF-%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AC%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B6%D9%8A%D8%A9.

Atallah, Nadine. "Have There Really Been No Great Women Artists? Writing a Feminist Art History of Modern Egypt." In Under the Skin: Feminist Art and Art Histories from the Middle East and North Africa Today, edited by Ceren Özpınar and Mary Kelly. Oxford University Press, September 2020.

Badran, Margot, "Dual liberation: Feminism and Nationalism in Egypt, the 1870s–1925," Feminist Issues 8, (1988)

Bavard, F., Translated by Rubens, A. (2021) . The politics of uncovering women’s bodies in nationalist and feminist agendas in Egypt (1882-1956) Clio. Women, Gender, History, No 54(2), 101-127. https://doi.org/10.4000/clio.20464.

Behairy, Sahar, Dr. Orabi Mohamed Fayad, and Fatima Ali. Souad Abdelrasoul: Like a Single Pomegranate. Almas Art Foundation, 2023.

Centore, Kristina L. "Technology, Time, and the State: The Aesthetics of Hydropower in Postcolonial Egypt." Master's thesis, Temple University, May 2020.

Davies, Claire. “The Egyptian School of Fine Arts.” Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism.

Davies, Clare. "Mahmoud Khaled: 'Painter on a Study Trip'." 2013. Accessed December 13, 2024. https://www.mahmoudkhaled.com/claredavies.

Hatem, Mervat F. "Economic and Political Liberation in Egypt and the Demise of State Feminism." International Journal of Middle East Studies 24, no. 2 (1992).

Hendrie, Amy. "Was Anwar Sadat a Feminist?" Retrospect Journal, 2022. https://retrospectjournal.com/2022/03/20/was-anwar-sadat-a-feminist/.

Kane, Patrick. "Egyptian Art Institutions and Art Education from 1908 to 1951." The Journal of Aesthetic Education 44, no. 3 (Fall 2010): 43-68.

Kane, Patrick. "Menhat Helmy and the Emergence of Egyptian Women Art Teachers and Artists in the 1950s." Arts, September 2022

Margaretta wa Gacheru, "Egyptian Artist: Not a Feminist but Knows What Feminism Is," Kenyan Arts Review, July 2021, accessed November 23, 2024, https://kenyanartsreview.blogspot.com/2021/07/egyptian-artist-not-feminist-but-knows.html.

Mhajne, Anwar. "Women’s Rights and Islamic Feminism in Egypt." Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, June 8, 2022. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2022/06/08/womens-rights-and-islamic-feminism-in-egypt/.

Nour, Samar. "في أطلس سعاد عبد الرسول عيون تبحث عن أرواحها في سماء بعيدة." Raseef22. Accessed November 23, 2024. https://raseef22.net/article/1092062-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A3%D8%B7%D9%84%D8%B3-%D8%B3%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D8%B3%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%B9%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AA%D8%A8%D8%AD%D8%AB-%D8%B9%D9%86-%D8%A3%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AD%D9%87%D8%A7-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B3%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D8%A8%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%AF%D8%A9.

Okeke-Agulu, Chika. "Politics by Other Means: Two Egyptian Artists, Gazbia Sirry and Ghada Amer." Meridians 6, no. 2 (2006): 117-149. Duke University Press.

Selaiha, Nehad. "The Fire and the Frying Pan: Censorship and Performance in Egypt." TDR (1988-) 57, no. 3 (Fall 2013): 20-47.

Van Nieuwkerk, K. "‘Repentant’ Artists in Egypt: Debating Gender, Performing Arts and Religion." Contemporary Islam 2 (2008): 191–210.

[1] Nour, Samar. "في أطلس سعاد عبد الرسول عيون تبحث عن أرواحها في سماء بعيدة." Raseef22. Accessed November 23, 2024

[2] Egypt was invaded and occupied by Britain from 1882 to 1956. The occupation began during the Anglo-Egyptian War when British forces seized control of the country in 1882. The British maintained control over Egypt for over seven decades until the Suez Crisis 1956, when the last British troops withdrew per the Anglo-Egyptian agreement of 1954.

[3] Davies, Claire. “The Egyptian School of Fine Arts.” Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism.

[4] Al Shahbari, Dana Adnan. "Modernist Encounters Across Borders: May Ziadeh and Virginia Woolf." Master's thesis, American University of Beirut, 2023

[5] Kane, Patrick. "Egyptian Art Institutions and Art Education from 1908 to 1951." The Journal of Aesthetic Education 44, no. 3 (Fall 2010)

[6] Atallah, Nadine. "Have There Really Been No Great Women Artists? Writing a Feminist Art History of Modern Egypt." In Under the Skin: Feminist Art and Art Histories from the Middle East and North Africa Today, edited by Ceren Özpınar and Mary Kelly. Oxford University Press, September 2020.

Okeke-Agulu, Chika. "Politics by Other Means: Two Egyptian Artists, Gazbia Sirry and Ghada Amer." Meridians 6, no. 2 (2006): 117-149. Published by Duke University Press.

Centore, Kristina L. "Technology, Time, and the State: The Aesthetics of Hydropower in Postcolonial Egypt." Master's thesis, Temple University, May 2020.

[7]Hatem, Mervat F. "Economic and Political Liberation in Egypt and the Demise of State Feminism." International Journal of Middle East Studies 24, no. 2 (1992).

Hendrie, Amy. "Was Anwar Sadat a Feminist?" Retrospect Journal, 2022. https://retrospectjournal.com/2022/03/20/was-anwar-sadat-a-feminist/.

[8] State feminism encompasses government policies and practices promoting women's rights and gender equality through formal institutions and legal frameworks. It actively advocates for education, healthcare, employment, and political representation. Sadat promoted state feminism while restricting the activities of civil society feminist groups such as women's rights NGOs through legal and funding restrictions and surveillance.

[9] Mhajne, Anwar. "Women’s Rights and Islamic Feminism in Egypt." Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, June 8, 2022. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2022/06/08/womens-rights-and-islamic-feminism-in-egypt/.

[10] Aly, Menat. "Gender Washing Autocracies in Egypt: Drawing on the Presidency of Anwar El Sadat and Hosni Mubarak."

[11] Selaiha, Nehad. "The Fire and the Frying Pan: Censorship and Performance in Egypt." TDR (1988-) 57, no. 3 (Fall 2013)

[12] For this reason, pioneering artist Gazbia Sirry left her teaching post at the American University of Cairo in 1981.

[13] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[14] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[15] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[16] Behairy, Sahar, Dr. Orabi Mohamed Fayad, and Fatima Ali. Souad Abdelrasoul: Like a Single Pomegranate. Almas Art Foundation, 2023, p 41

[17] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[18] Behairy, Sahar, Dr. Orabi Mohamed Fayad, and Fatima Ali. Souad Abdelrasoul: Like a Single Pomegranate. Almas Art Foundation, 2023, p 49

[19]Almas Art Foundation. "Souad Abdelrasoul." 16:13. 2023.

[20] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[21] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[22] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[23] At her 2021 solo show at Circle Gallery in Nairobi, Kenya

[24] Almas Art Foundation. "Souad Abdelrasoul." 16:13. 2023.

[25] "Souad Abdelrasoul: Film." Al Masart Foundation. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://www.almasartfoundation.org/artists/30-souad-abdelrasoul/video/.

[26] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[27] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[28] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[29] Nour, Samar. "في أطلس سعاد عبد الرسول عيون تبحث عن أرواحها في سماء بعيدة." Raseef22

[30] "Souad Abdelrasoul: Film." Almas Art Foundation. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://www.almasartfoundation.org/artists/30-souad-abdelrasoul/video/.

[31] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[32] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[33] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[34] Almas Art Foundation. Souad Abdelrasoul. YouTube, published October 2023

[35] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[36] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[37] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[38] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[39] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

[40] "I believe that a man's masculinity is linked to his work. A man often asserts his masculinity by creating monumental and grand works, as if saying, 'Here I am, see how great and significant I am.' On the contrary, femininity is usually not tied to achievement. This leads women to seek beauty in their works… loaded with tremendous emotions…This notion clearly explains, in my opinion, why men dominate money and power in the world to a large extent. These domains do not need a conscience, and in my view, do not need emotions either." "Souad Abdelrasoul: Film." Al Masart Foundation. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://www.almasartfoundation.org/artists/30-souad-abdelrasoul/video/.

[41] Souad Abdelrasoul, interview by Iona Stewart, Cairo, November 7, 2024

Comments on Attempts to Escape Drowning: Souad Abdelrasoul’s Women of the Nile