Introduction

Since the Greeks, memory has been understood as the ability to collect information from our world and reimagine it[1]. Memory can be triggered by a variety of elements connectable to a lived experience. It has been used in art to reflect personal experience or collective trauma. Understanding memory in art as a conversation between artist and viewer, allows the impact a memory can have to be contingent on the chosen output. While painting, sculpture, and photography have their ways of documenting memories, a special attention has to be paid to the medium of printmaking. The creation of a matrix, whether it is a carved relief on a wooden board or the engraved lines on a metal plate, is the physical incarnation of the maker's inspiration. Therefore, print has the capacity to evoke memory in both the function and the concept as no other technique has[2].

In the 20th century, a deep engagement in printmaking experimentation took place across Europe and the United States. Pablo Picasso and other artists started to explore different approaches of this medium at the beginning of the century[3]. At the time of the rise of Pop Art[4], a group of artists including Leonard Baskin and Mauricio Lasansky developed a genre inspired by humanist philosophy[5]. By being interested in the investigation of the human psychological state, Baskin and his contemporaries used graphic marks to evoke an inner turmoil[6]. The teeming environment attracted the Iraqi artist Dia Al-Azzawi, who travelled to Salzburg in 1975 to participate in a printmaking workshop[7]. The exposure to this technique and its artists revealed to be a pivotal shift in his art. Inspired by Baskin’s humanistic approach in printmaking, Al-Azzawi began using printmaking techniques to evoke and express emotions concerning the violent political events in the Middle East.

Al-Azzawi created many prints that encapsulate collective memories of his region. Taking into consideration his prints titled We Are Not Seen but Corpses (1983), he attempted to engrave a memory of human oppression. Through the constitution of a matrix, Al-Azzawi expressed his rejection of violence toward civilians. The chosen aesthetics were meant to move the viewers emotionally, in order to allow them to experience a sensation of pain and violence. Viewing memory as an imaginative practice, Al-Azzawi used We Are Not Seen but Corpses to create new possible realities.

Memory and Art

Memory in art is the re-imagination of a past, done in the present through physical material processes. Whether in relation to an ancient culture, historical events, contemporary struggles, or personal stories, art creates a memory by awakening empathy in a viewer. The American art historian David Freedberg argues that the process of evoking memory in art has a physical impact. A body depiction, through a mirroring process, can provoke a viewer's body to be emotionally impacted or even to react with small movements. Furthermore, Freedberg argues that by arousing emotions through the body, the artist reinforces the viewer’s declarative memory – one’s storage of facts and personally experienced events. In other words, by giving the viewer new experiences, the artist contributes to keeping a specific memory or narrative alive.

The visual input that evokes memory does not necessarily need to be figurative. In fact, there are different ways through which visual signs work. Where figurative representations work through resemblance, abstract signs work through convention. The semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce worked also with a third type of sign, the index. According to Peirce, the meaning of indexes is not explicit, but it relies on previous experiences and acquired knowledge[8]. The meaning of a sign can emerge as a cultural belief relevant to a specific group, such as the cow being a symbol of divine beneficence for Hindus. A sign can also carry meaning that is universally read, like smoke representing fire. A good example of the use of these diverse types of signs in art is the Guernica of Pablo Picasso. The artist created the artwork in response to the tragic events brought by the Spanish Civil War. In the painting, the artist uses the universal sign representing tears to evoke a memory of sadness and desperation. He also uses the image of a woman holding a child, which from a Christian perspective can be understood as the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus.

Developments in Al-Azzawi’s Art

Memory has been a constant in Al-Azzawi's art. During his studies in archeology at the University of Baghdad (1958-1962), Dia Al-Azzawi experimented with a form of drawing that investigated the ancient and folk art of the region, Mesopotamian visual culture[9] in particular. Rather than studying the past as a static dimension, he used the knowledge of the past in an active and critical way to understand the present, and move towards the future[10].

The consolidation of Al-Azzawi´s identity as an artist took place during the cultural efflorescence of the ‘60s, in which artists in different disciplines broke the old forms and engaged in new ways of thinking about art. Together with the artists Ismail Fattah, Rafa Al-Nasiri, Mohammad Muhraddin, Saleh al-Jumaie and Hashim Samarji, Al-Azzawi formulated a manifesto titled Towards the New Vision (1969)[11]. Here, art is described as “the practice to take position”, as “a mental rejection of all that is wrong in the structure of society” and as “a practice of constant creation”[12]. Accordingly, they refused the idea of art as a representation of the world and embraced the concept of art as an imaginative space, not as fantasy but where new possible realities form[13]. This approach needs to be understood not merely as a political activism, but also as a reflection on what it means to be human. Thus, fundamental to the contemporary artist is to recognize the greatness of uniting with other artists through artistic production[14]. By making these arguments, they promoted the formation of an Arab identity[15], rather than an Iraqi identity, which previous art groups like Friends of Art Society, formed in 1941, had pursued. Accordingly, Al-Azzawi expanded his network to include writers and artists from other Arab countries. These relations led him to feel emotionally involved in tragic events that concerned people from other Arab countries or other ethnic groups, such as the Kurds[17].

Al-Azzawi and the other members of the New Vision group felt an affinity towards the Palestinian cause in their effort to form an Arab art. In a very first attempt of showing solidarity with the Palestinian cause and support for the resistance, Al-Azzawi designed a cover for the Iraqi magazine Shi'r, in 1969. It depicted an Iraqi soldier who died while fighting together with the Palestinian resistance[18]. In line with his artistic formation, Al-Azzawi did not limit himself to work with the current struggle of Palestinians, but also made sketches inspired by popular Palestinian texts and folk songs. The further development of the sketches was published in 1972 under the name of A Witness of Our Times. The Journal of a Fida'ee Killed in the Jordan Massacre of 1970. The book connected preliminary ethnographic studies with material related to the struggle, such as resistance songs and military statements[19].

For Al-Azzawi, leaving Iraq in 1975 meant working with memory from a new perspective. In response to the tragic attack on the Palestinian refugee camp of Tel Al-Zaatar, by Christian militias in 1976, Al-Azzawi created a series of prints called The Body's Anthem (1976). Similarly, in this series, Al-Azzawi makes use of poem. Although, in contrast to previous works about Palestinian resistance, The Body´s Anthem aims to create a ‘dramatic build-up’. In fact, the emphasis on the heroic action present in A Witness of Our Times turned in The Body's Anthem to a focus on the suffering of the oppressed[20]. Al-Azzawi asserts that this body of work is an “expression that attempts to create a free memory that persists against oppression”[21] – the image created becomes projected into the future, where the experience of oppression is both visible and surpassed[22]. This concept of persistency resonates with Freedberg´s idea of a memory that lives through the viewer's experiences in the present.

.jpg)

Memory in We Are Not Seen but Corpses

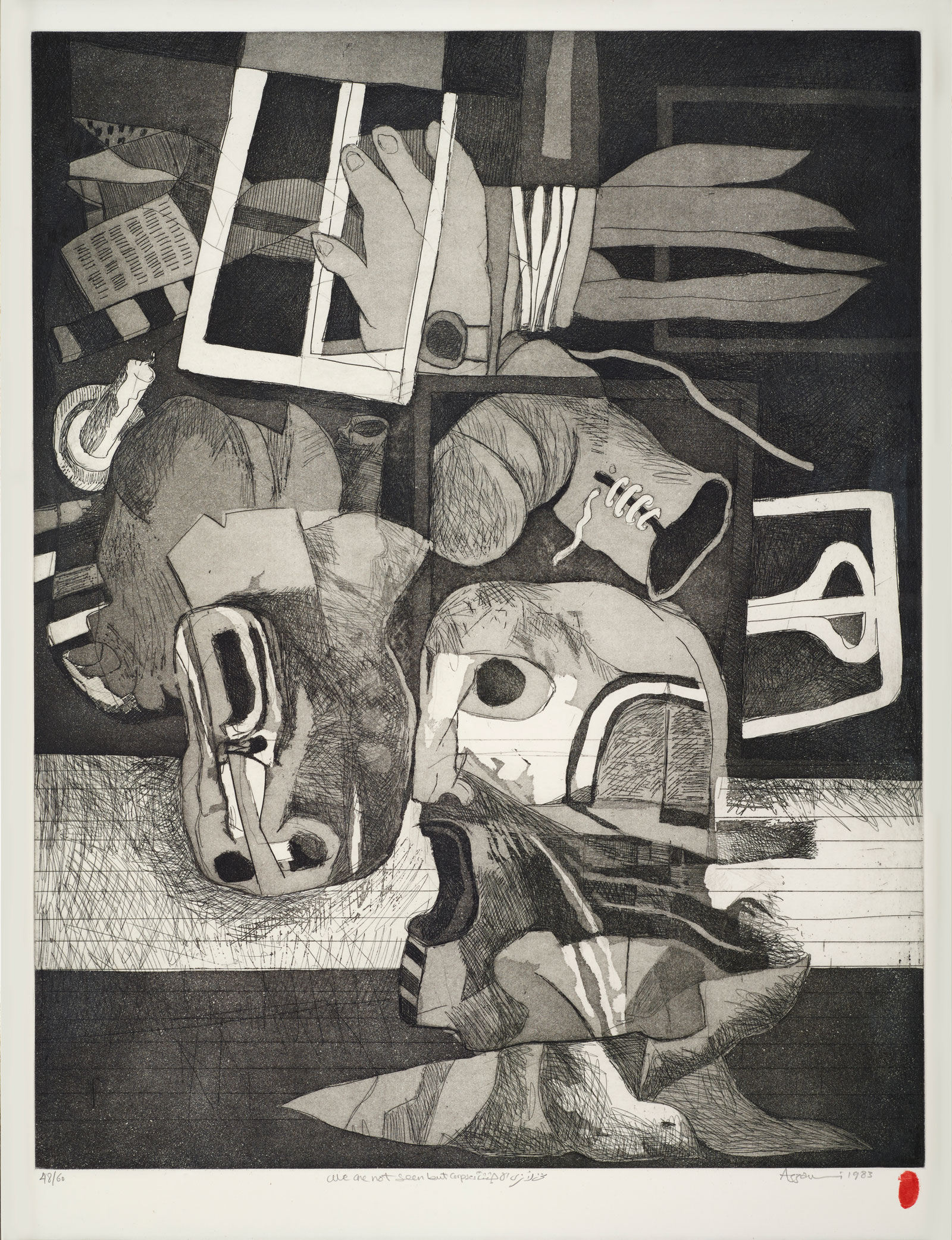

Among the many works of Dia Al-Azzawi, We Are Not Seen but Corpses (1982-83) epitomizes his technique of representing an isolated subject matter that can be understood universally. This work is a series of nine black and white prints made through the techniques of etching and aquatint, part of the Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF) collection in Beirut. The date “9/12” written on some of the prints makes a reference to the massacre of Sabra and Shatila on September 12, 1982[23]. The assemblage of abstract figures[24], that compose the collection, sharply conveys a message of pain, distress, and chaos.

The printmaking techniques of etching and aquatint play a pivotal role in creating memory, allowing Al-Azzawi to materialize his thoughts. Etching consists of scratching the wax layer on a metal plate, that will afterwards be placed in an acid bath. Furthermore, the longer the metal plate is left in the acid, the deeper the incision will be. Consequently, the more ink can be held in the carved lines, the darker the print on paper will be[25]. The soft surface of the waxed metal plate allows the hand of the artist to move freely[26]. Etching can therefore be seen as the perfect means through which Al-Azzawi can best express his ideas.

For Al-Azzawi, the line is a very important element because of its capacity to convey what the imagination brings without relying on other elements[27]. The ways the lines are engraved (e.g. if they were drawn slowly or quickly, tracing a drawing or by freehand) create a connection between the artist's experience in making the piece. The connection also extends to the viewer's experience of the produced image. For instance, in figure 2, the two elements that resemble human faces are brought to life by overlapped lines of different thickness and directions. The hysterical character of this chiaroscuro[28] can make the viewer feel the artist’s hand moving on the metal plate with rage. Furthermore, the particularity of creating lines by etching is that they are not merely drawn, but become ‘alive’ through the chemical reaction of the acid that bubbles and eats the metal. Accordingly, the vicinity and the depth given to these lines in figure 2 can be seen as an expression of how the pain penetrates the human body.

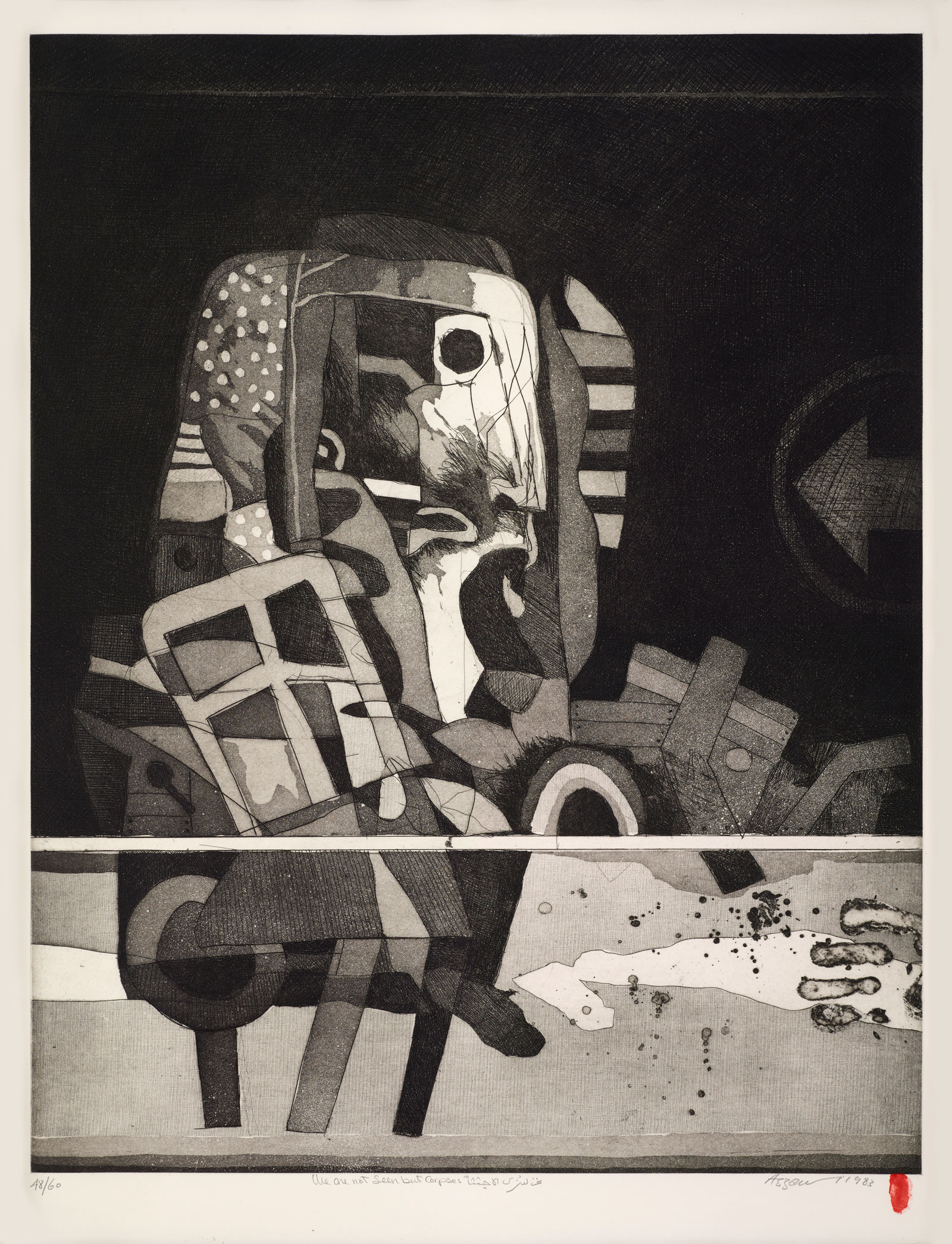

In comparison to the etching, the technique of aquatint shows another type of materiality. The process consists of covering the metal plate with a porous acid resistant resin. The acid, eating around the grains, creates a soft effect similar to watercolors. As in etching, the longer the exposed surface stays in the acid, the darker it will turn. Thus, by gradually covering parts of the plate, the artist can create a distinctive scale of grey[29]. This technique is much more time-consuming than etching, and the movements of the artist's hand do not appear as clearly in the final result.

The slow nature of aquatint stays in contrast with the chaotic nature of Al-Azzawi's images. In figure 3, the main image shows human resemblance. The different zones of grey, through which it is composed, create the effect of a person carrying an indistinguishable number of objects. By choosing not to present the ‘objects’ as identifiable, he leaves the grey surfaces with the task of catching the viewer's attention. In fact, the degradation in tonalities, ranging from dark black to different shades of grey, expresses an overwhelming and chaotic sensation. The scene can be connected to the action of escaping with one's belongings, constituting a person's life and identity.

Different types of visual signs are also used to evoke a memory of violence. In accordance with the ideology of the New Vision manifesto, Al-Azzawi uses signs that evoke universal meanings. Therefore, rather than an accusation towards the Christian militia that committed the massacre, he attempts to convey pain that every viewer can relate to. Because the human mind has collected pictures of what a human body looks like, having a few elements in an artwork is sufficient to evoke the memory of a human appearance. Consequently, the elements that resemble the human body, like the two figures with open mouths and big empty eyes, in figure 2, can emotionally arouse the viewer through a mirroring process. Because the same sign can have more than one function, the open mouths in figure 2 produce meaning also through indexicality. The open mouths, in fact, recall the memory of emitting a loud sound, which can in turn awaken a sense of fear in the viewer.

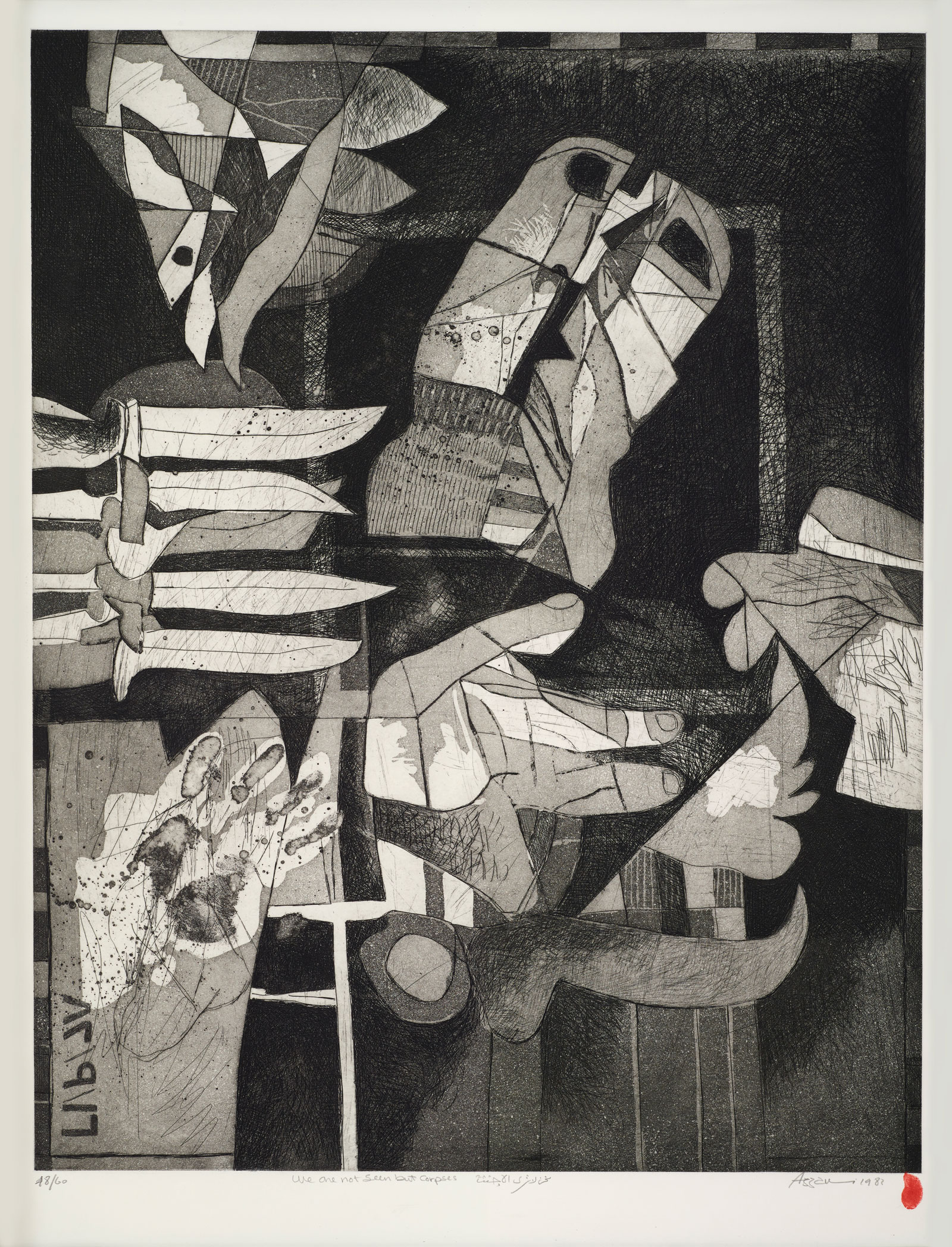

Meaning can also be produced through the collaboration between signs. In figure 4, there are four figures in the center left of the printed image that resemble knives. Close to the points of the knives is a figure that resembles a human head. Because of its inclination towards the right side of the picture, it gives a sensation of falling. The representation of knives, together with the figure of the head, creates a powerful index of violence on the human body. More specifically, the representation of a knife functions as an index for the experience of cutting. The face composed by geometrical forms and divided by thick black lines can evoke a sensation of being decomposed. Without a direct visual interference between these elements, Al-Azzawi manages to convey the sensation of being cut.

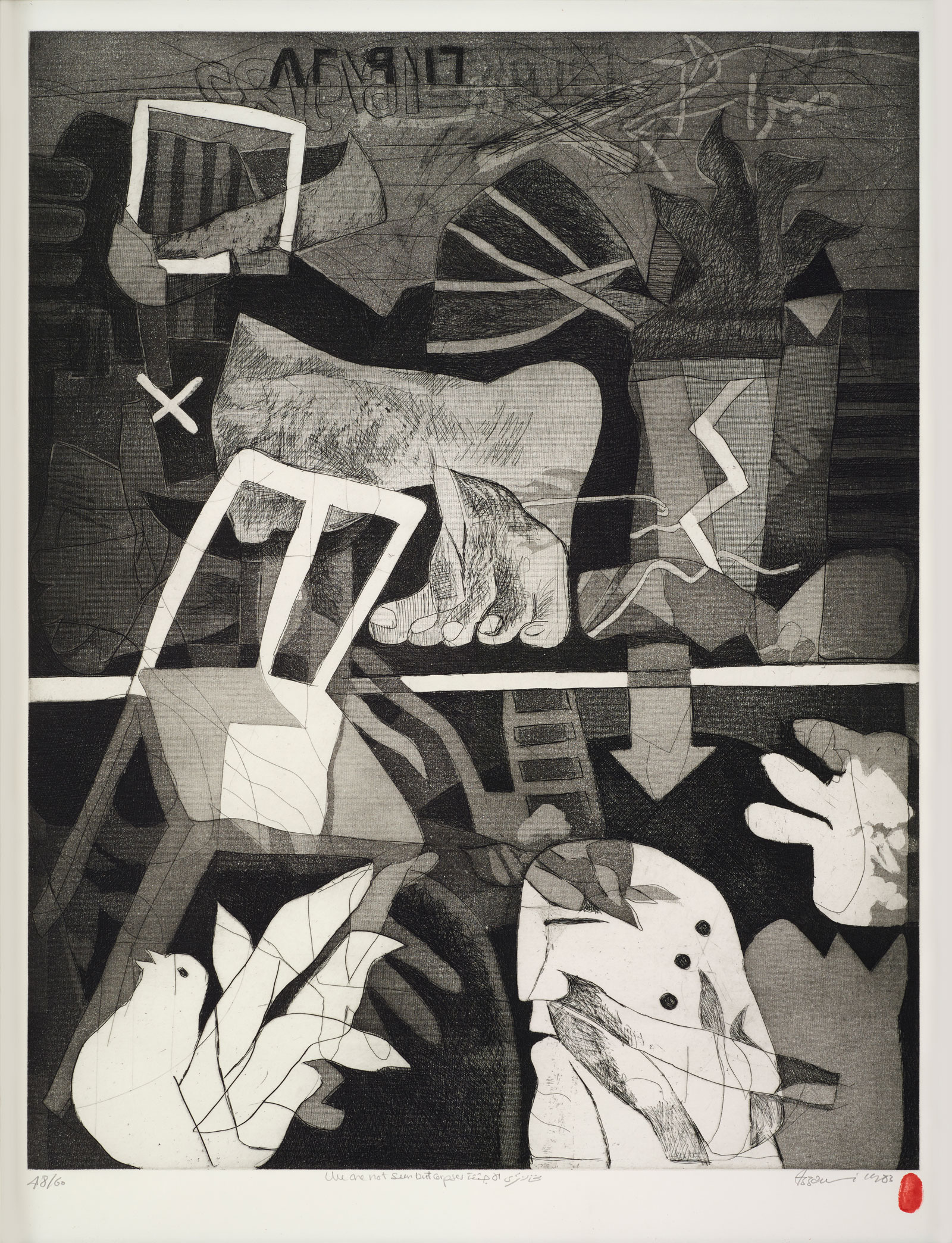

Al-Azzawi´s idea, that art has to criticize society and produce new possibilities, comes to clear expression in figure 5. In the upper part of the printed image, elements like the wavy forms that recall the image of fire, or the representation of a foot detached from the rest of the human body, express Al-Azzawi´s indignation and refusal of violence against civilians. Contrastingly, in the lower part of the printed image, a figure resembling a dove and a figure resembling a human face convey a sort of calmness. A symbol is the type of sign that carries meaning by convention. Originally a Christian symbol of peace, the dove has become quite widespread through extensive use in Picassian art. In the second symbol, the figure of the face, differs from the faces in figure 2, having its eyes and the mouth closed. Again, through a mirroring process and indexicality, the depiction of the face can produce a memory of physical relaxation and inner peace. Furthermore, the indicator arrow, that originates in the upper part of the picture and points down, might signify the idea of moving towards a future where the experience of oppression is surpassed but the memory still lives.

Al-Azzawi, with We Are Not Seen but Corpses, has offered an immense contribution to the memory of the Palestinians. When printed materials are transformed into printed images, experiences can be transformed into tangible, tactile traces of memory, experienced through art objects (Barthes, 2000). Through the material process of scratching and leaving the acid to eat the metal, Al-Azzawi express his rage and refusal of violence against civilians. Consequently, the materialization of the indignation at the atrocities committed against the Palestinians is a way to keep the memory present and accessible.

The memory of the massacre of Sabra and Shatila is meant to live through the viewer's physical responses that Al-Azzawi tries to stimulate through an accurate choice of signs. Though their experiences, the viewers contribute to creating a memory that persists against oppression. Through his use of both universal and cultural symbols, Al-Azzawi was able to relay a personal message to a universal audience. By choosing a visual language that speaks to every human, he brings the Palestinian oppression from being a Palestinian problem to being a human problem. In this way, the memory of the Palestinian struggle lives beyond its own socio-cultural boundaries.

Content Tracking by Wafa Roz

Edited by Elsie Labban

Comments on Dia Al-Azzawi We Are Not Seen but Corpses: Engraving Memory