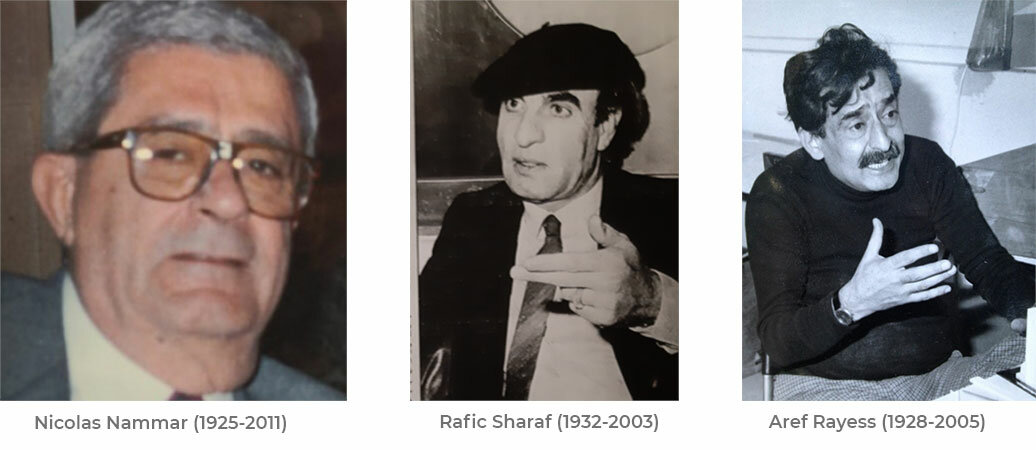

The first generation of visual art educators were key to the development of the Institute of Fine Arts at the first and only public university in Lebanon, the Lebanese University (UL). This group, most of which was composed of ALBA graduates, included Nicolas Nammar, Jean Khalife, Shafic Abboud, Yvette Ashkar, Nadia Saikali, Mounir Eido, Halim Jurdak, Rafic Sharaf, and Hussein Madi. Non-ALBA graduates included Rashid Wehbe who studied in Cairo; as well as self-taught artists Elie Kanaan and Aref Rayess, both of which were trained in Paris. All of those artists later became Lebanon’s most celebrated modernists.

Painter and cultural activist Nicolas Nammar was a leading and founding member of the UL Institute of Fine Arts. He held the dean's position from 1968 till 1973. He remained a professor from 1965 until his retirement in 1988. Painter and sculptor Aref Rayess, also an influential and founding member, taught at the institute from 1966 until 1980. Painters Rachid Wehbe, Jean Khalife, Elie Kanaan, Nadia Saikali, and Rafic Sharaf joined the institute at its inception. Khalife taught at the institute until his untimely death in 1978. Kanaan and Saikali taught till 1974. Sharaf directed the institute from 1982 till 1988. Painter Yvette Ashkar taught at the institute from 1966 till 1988, while painter Shafic Abboud, based in Paris, offered periodic summer courses from 1968 till 1975. Hussein Madi, a Painter, and sculptor came at a later stage and taught at the institute from 1972 till 1987. Halim Jurdak, specializing in engraving, started the first printing studio at the institute, and Mounir Eido introduced courses in modern abstract sculpture.

Intuitive Pedagogical Approach1

Most artists mentioned above were trained at the École des Beaux-Arts or La Grande Chaumière in Paris. They were exposed to the European art scene and frequented the studios of many modern artists. Several artists experienced the rigorous practice at the Beaux-Arts, which was based on the classical arts of ancient Greece and Rome, and the free learning at La Grande Chaumière, where both professional and amateur students could train at will. Most were inspired by the mentorship of modern European artists like André Lhote, Fernand Leger, and Jacques Villon. As such, they became equipped with a mélange of pedagogical approaches and methods.

Those artists-educators were practicing artists and proficient in one or more fine arts areas such as painting, drawing, sculpture, printing, or graphic design. They had an adequate understanding of European art history; however, they scarcely emphasized analytical art theory. Instead, they mainly focused on studio practice in their teachings.

It is worth noting that during that period artists found their way into teaching intuitively. Visual art teachers did not have to complete a teaching diploma, which would have been complementary to their art education. Visual arts tutors abided by the conventional curriculum set by the dean of the institute and a counseling committee. The curriculum included studio courses introducing students to the procedure and materials of different drawing and painting media and their various applications and techniques. Typically, a medical doctor would give anatomy lessons to acquaint students with human morphology; a civil engineer or an architect would teach linear perspective and technical drawing courses. The program also included courses on aesthetics, modeling, and sculpture, while copperplate engraving and printing techniques were part of the elective courses. If students needed theoretical information in the field of art, they had to conduct research in the university’s library.

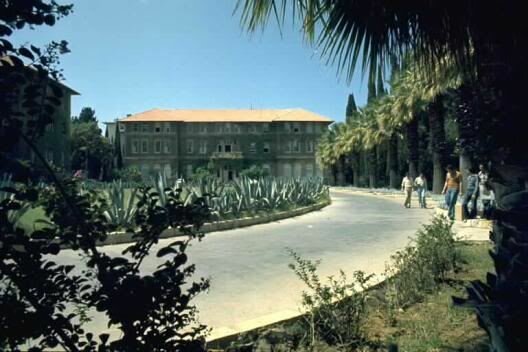

Abstraction was in vogue at the period. However, teachers did not impose any specific style of practice. Instead, educators reserved the choice of style, theme, and subject matter to students. Generally, tutors at the UL Institute of Fine Arts advocated travel and encouraged students to draw and paint en Plein air. For instance, second-year students were often accompanied to the American University of Beirut (AUB) to draw and paint its beautiful campus landscape(fig.1). Students of the final fourth year were granted a two-week trip to Europe, usually one week to Paris and another to London, where they would explore the art world firsthand.

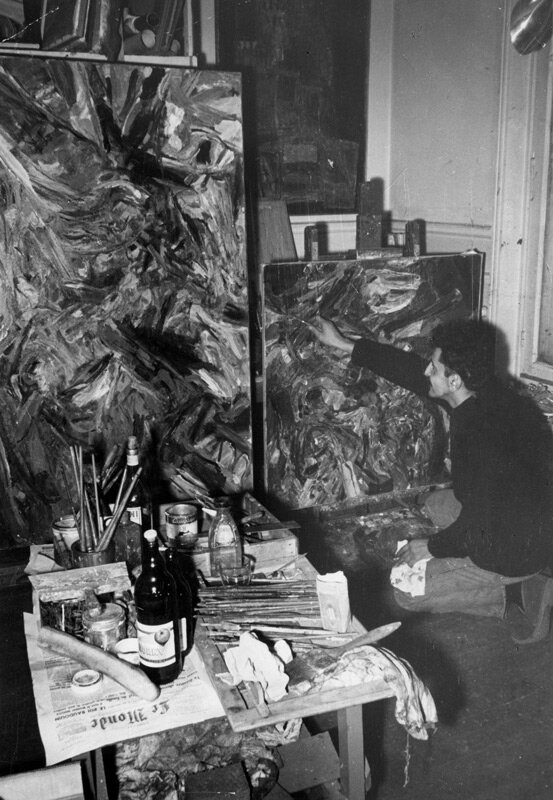

In a recent interview at the Dalloul Art Foundation, artist Fawzi Baalbaki and graduate of the UL institute, recalled that, “although the institute had no specific didactic policy, artists were passionate about teaching; they taught the way they saw best.” Baalbaki said, “Rachid Wehbe (fig.2) taught us drawing with charcoal. Aref Rayess instructed us on creating a painting's structural composition, and Rafic Sharaf taught us color theory and painting. Shafic Abboud (fig.3&4), the most skilled of all, gave courses on the physical and chemical properties of color and demonstrated the preparation of pigments at the lab.” With assertion, Baalbaki continued, “The management was strict and vigilant, and the institute was one to be proud of before the unfortunate Lebanese civil war erupted.” He expressed that “during the war, the institute was divided into two branches: one in the UNESCO area and the other in Furn El Chebbak and became politicized and lead by the militias.”

Similarly, in a telecom interview, artist Mohammad Rawas, a graduate of the UL Institute of Fine Arts, stressed the lack of a defined pedagogical strategy at the institute. In his own words, he explained, “Artists promoted the quality and merits of their artistic style and temperament. This applies to all the teachers I had studied with at the institute.” With a critical tone, Rawas proceeded, “It is their ‘aura’ that took over the class and affirmed their presence." He continued, “Aref Rayess was charismatic, sarcastic, and funny, while Rafic Sharaf was harsh” When asked about Jean Khalife, Rawas replied, “He was decent, shrewd, and calm. The one thing I certainly grasped from Khalife was the boldness in applying brush strokes and spontaneity.” Rawas added, "We were aware of each teacher’s style; we attended most of their exhibitions.”

Rawas expressed his astonishment when he first saw Rafic Sharaf’s ‘Antar and Abla’ series comprising oriental paintings inspired by mythological narratives. Most of those paintings depict the invincible Arabian hero Antar riding a horse(fig.5), and at times having his beloved Abla next to him adorned in a traditional Abaya. This fantasized theme helped Sharaf overcome his distress following the 1967 Arab defeat. Rawas realized that Sharaf’s works were different than his earlier melancholic depictions of migrating birds and solo trees in deserts. This is one example of how he learned the variable styles and themes of his art tutors.

Reminiscing Beirut's heydays, Rawas concluded, “Those were the golden days in the early 1970s; there were so many shows to attend and activities happening in a city buzzing with cultural events.” Speaking about the inspiring cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity in Lebanon and the institute back then, Rawas declared, “We never asked about one's religion or one's background; the environment was so enriching and inspiring.” Indeed, students at the institute came from different regions of Lebanon.

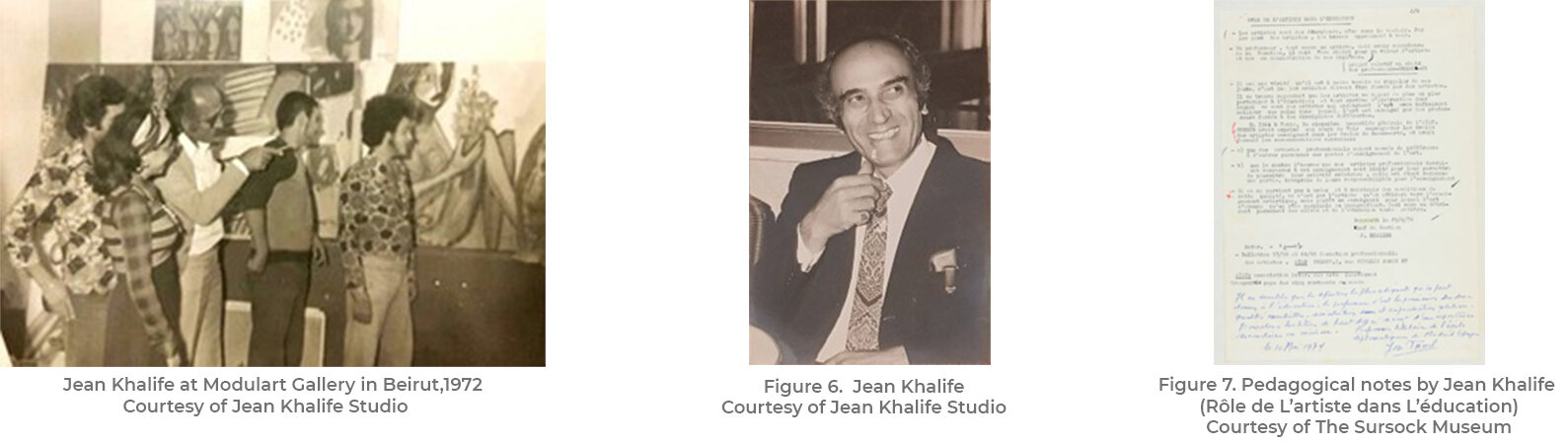

‘Les Memoires’ de Jean Khalife (1925-1978)

Defining an artist-educator, the late Jean Khalife (fig.6&7) wrote, “Artists are educators by nature, even if unaware of this fact. Through the eyes of an artist, the spectator learns to see. An educator is like an artist […] he must be chosen for his artistic vocation and not his academic achievements. I believe that artists must be trained by artists […] Any educational system in which artists teach art will be certainly better than one in which art is taught by professors trained in different disciplines.”2 On mentorship, Khalife noted, “I believe I am not entitled to forge what the student wants to express. I do not interfere except as a last resort and when asked. I can teach him a specific technique, but the expression belongs only to the pupil.”

“The goal of our teaching,” he continued, “is to guide the student of fine arts towards acquiring knowledge and techniques while stimulating the students' creative spirit. To preserve our beliefs and dogmas, we serve as exemplars and guides to ensure open-mindedness and in-depth knowledge for the pupil. We encourage the student to carry out extensive research now and in his future profession as a painter or sculptor.”

Finally, reflecting on the role of art, Khalife stated, “I am for the universality of art. What matters to me is the artist’s outlook on the world. Art has to touch the whole of humanity. The pioneering artist is not a product of heritage, but rather its creator”.

Comments on Fine Arts Education in Lebanon: Part 2