I have my own view, and an extra blade of grass.

Mine is the moon at the ends of speech,

and the blessings of birds,

and an immortal olive tree…

Mahmoud Darwish, Ana min Hunak[1]

The latter verses, from the famous poem Ana min Hunak (I am from there) by Palestinian poet and author Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008), express a strong feeling of nostalgia. They share with the reader a distant memory of what used to be the author’s homeland, Palestine. Darwish’s personal story of being forced to leave his village, in Western Galilee, for Lebanon in 1948, is one of more than 750,000 people[2]. When the state of Israel was established in the region that year – launching the first Arab-Israeli war – the local Arab population was expelled from their land. The extent of violence of this historical event was so great that it was called “al nakba” (catastrophe) by Syrian historian Constantin Zureiq (1909-2000). People were forced to settle in the neighboring countries, sparking a massive wave of immigration into Lebanon and Jordan.

It was then that Palestinians knew they had to fight for their rights, in the hope of retrieving their home one day. Yet, the fight has not only manifested through the language of weapons, but also the emotional power of words and visual art. In fact, an important, rebellious movement quickly emerged, gathering intellectual figures from the diaspora and the Palestinian territories (West Bank and the Gaza Strip). In their own way, they were denouncing the injustice and the tragedy, of which they were victims. Writer Samih al Qasim (1939-2014) wrote an impressive corpus of poems, through which he imposed a nationalist genre. Similarly, Edward Said (1935-2003) qualified the Zionist movement as a European modelled ‘colonial project’ in his book The Question of Palestine (1979). Naturally, this movement reached the cultural and artistic circles. A significant part of modern and contemporary Palestinian artists, like Mustafa El Hallaj (1938-2002) and Abdulhay Musallam Zarara (1933-2020) to name a few, never hid their solid political commitment in their artworks. They used powerful iconography, combining multiple motifs like the dove or the cactus (sabra), which symbolize freedom and resistance.

Armed conflicts and religious tensions between Palestine and Israel never stopped. They continued to affect the geo-political history of the Middle East in the 20th

century. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the Palestinian rebellion goes beyond the claim of getting a territory back. It is certainly a considerable effort to prevent the disappearance of the Palestinian identity. It is even a great challenge since it is conducted by a population mostly in exile. Hence, in parallel to the uncountable massacres of populations, how is it possible to resist the annihilation of a culture, a history, and a tradition? Art and literature turned into a mobilization tool, used to perpetrate a narrative that has been in permanent danger of being neglected.

Al Nakba, the ‘Year Zero’

Palestine is a land with thousands of years of history. It is a place where numerous civilizations succeeded one another. However, it seems that the year of al nakba in 1948 is the most memorable one. It was stamped as ‘year zero’, as though the past had completely disappeared. Al nakba effectively marked the beginning of a pivotal chapter in the regional and global history, when the Arab Palestinian natives suddenly lost everything. This included material and human loss, as depicted in the heartbreaking painting Here Sat My Father (1957) (fig.1). In addition to the violation of human rights, the Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury highlighted this idea of loss: “They lost their land which was confiscated by the newborn Israeli state. (…) They lost their cities. (…) They lost their Palestinian name”[3].

The word ‘al nakba’ implies a traumatic experience, to which every Palestinian, young and old, could relate to directly or indirectly. Only a small number could find a better place to reside in, while the others were left to start everything from scratch. This was especially the case for those who found themselves in the overpopulated refugee camps. Their majority were forced into the latter circumstance as the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) registered an evolution of 80,000 refugees in the camps in Beirut, from 1948 to 1970[4]. Thus, the trauma had been seared in the collective memory of Palestinian people through generations.

Nonetheless, in the artistic community, this trauma is inked to the personalities of the practitioners. Abed Abdi (1942-), Amer Shomali (1981-), and Abdul Rahman Katanani (1983-) all lived in refugee camps. This significantly shaped the visual language of the artists, as well as their careers – sometimes associated to politics. Among the most relevant examples, the prominent figure Ismail Shammout (1930-2006), turned his entire practice into a political oeuvre, once saying: “De 1950 à 1970, ce furent des tableaux représentant une certaine évolution. C’était une idée sur la cause palestinienne exprimée par un artiste, ainsi que l’évolution de cet artiste à travers la cause palestinienne” [5].

It is important to highlight that this traumatic phenomenon not only deprived the Arab Palestinian natives from their land, but also from their history and the identity to which they were affiliated[6]. Consequently, in response to the colonial politics driven by Israel, it was urgent to the Palestinian community to mobilize in order to warn the international opinion about the ongoing situation, and, by extension, not to sink into oblivion.

The ‘Homeland in Exile’

As author Edward Said (1935-2003) highlighted in the article “Permission to Narrate” (1984), one of the difficulties in establishing the history of the Arab Palestinian natives is the dispersal of the population. The majority of imminent Palestinian artistic and intellectual figures in the 20th century, who highly contributed in developing this narrative, were young when they immigrated to another country. Often enough, they eventually spent most of their lives abroad, sometimes going from place to place. This was the case with artist and author Ghassan Kanafani (1936-1972), who lived in Damascus, Kuwait, and Beirut.

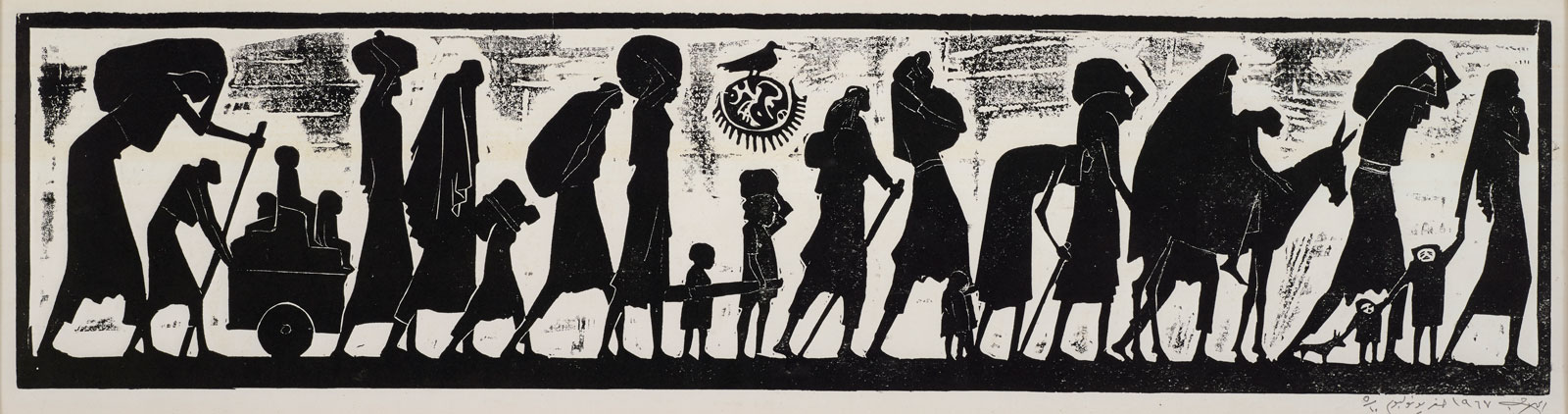

Needless to say, the theme of exile is one of the main characteristics of modern Palestinian prose, poetry, and art. Perhaps, it is out of a necessity to externalize their thoughts and feelings, that the authors and artists gave rise to such a production. It reflected the difficulty of leaving the homeland, and the sentiment of up-rootedness. In a way, they were the first archivists of their own history, like in the work Untitled by Mustafa El Hallaj (1938-2002) (fig. 2) painted in the year of the Six-Day War, which again provoked an important wave of migration.

Figure 2 Mustafa El Hallaj, Untitled, 1967, woodcut print on paper, edition 5/10, 18.5 x 70.5 cm.The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art

Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

However, all these years of wandering never let them forget about their roots in Palestine. On the contrary, the exile exacerbated their sense of patriotism. This even pushed them to take part in Palestinian activism. “It [world Zionism] stole the flag and changed it, stole the name and changed it, stole our place in the United Nations, falsified maps, encyclopedias, and dictionaries, and stole Palestinian popular culture and displayed it by Israeli. Yet it could not steal the living Palestinian consciousness, whose production has lived on in poetry, literature, and the arts as a historical archive growing out of this land”[7].

Resistance would then mix with artistic creation, as evidenced by the poetic writings of Tawfiq Ziad (1929-1994). In the 1960s, the concept of sumud, meaning ‘steadfastness’, became an ideology. It developed in Palestinian political strategy, as well as in cultural and artistic circles, against the Israeli settlement. However, the resistance to military occupation required the establishment of formal and official structures to protect the people and coordinate the fight.

The Palestinian resistance federated and reinforced the entire community, which was spread all over the world. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO, Munazzamat al-Tahrir al-Filistiniyyah) was founded in 1964 in Jerusalem. Many artists and intellectuals joined the organization. Among them were Ghassan Kanafani (1936-1972), Majed Abu Sharar (1936-1981) and Kamal Nasser (1924-1973). Five years later, Ismail Shammout (1930-2006) established the Union of Palestinian Artists (Itihad ‘Aam lil-Fannanin al-Tashikliyyin al-Falistiniyyin) in Beirut, being the Secretary General until 1984. Although essentially different, those examples of initiatives were thought to give Palestinian people an official, and quite stable, representation wherever they were residing. Even though they were deprived from an actual limited territory, a form of national awareness emerged from these organizations.

The Attachment to the Land

The question arises as to how the Palestinians could enforce their rights over a land, in which the politics Israel undertook a vast settlement program. The latter is especially justified by the Zionist ideology, which claims a national home for Jewish people in the region of Canaan. This claim is based on the attachment to the Holy Land, where Jerusalem occupies an important place in Judaism. Consequently, there is a clear intention to uproot the Palestinian people, visible in the symbolic of the olive tree.

As a source of livelihood, the exploitation of olive has always been part of the daily life in Palestine (fig.3), where the groves are mainly located in the occupied West Bank. As the conflict was intensifying, the olive tree turned into an emblem of resistance in the Palestinian collective awareness. On the Israeli side, this became a target for its conquest of territories, leading to a huge campaign of uprooting of olive trees[8].

Figure 3 Palestinian women crushing olives,1900- 1920.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division,

LC -DIG-matpc-01258, G.Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection.

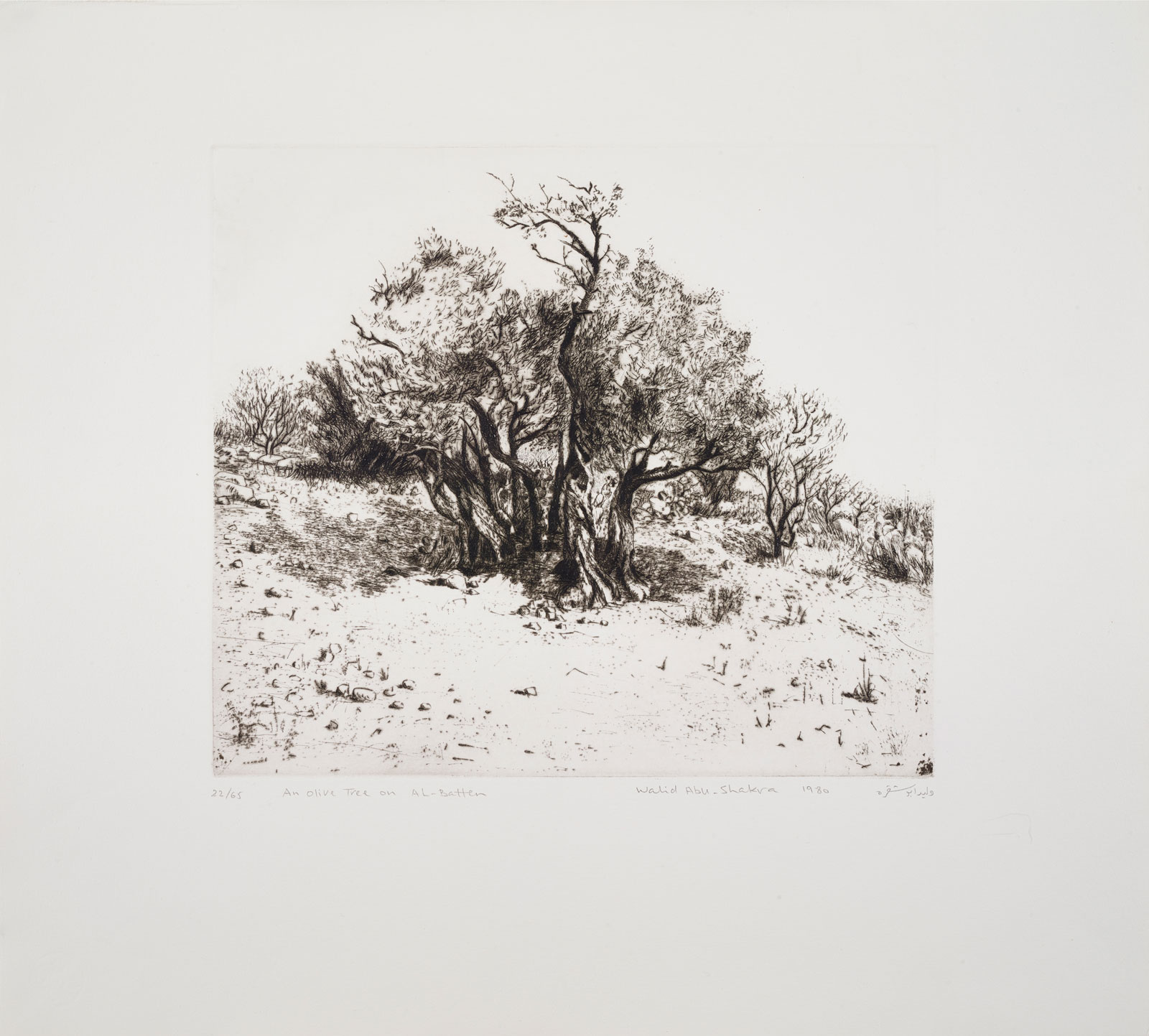

Embodying the nationhood, the olive tree is etched in the Palestinian collective memory: ‘Palestinians often express their bond with the land by depicting the ‘fruits of the earth’. The olive tree in particular – with its gnarled roots and ‘tormented’ stem (…)[9]. It is the metaphor of a deep rooting on the soil, that some poets like Mahmoud Awad Abbas and Assaad al Assaad, celebrated. It goes without saying that it was also integrated in the artistic creation. Being used as a visual emblem, especially in the oeuvre of Walid Abu Shakra (1946-2019) fig.4), the olive tree translates the ideology of sumud. While Palestinian people were living with no country, the olive tree links them to their homeland.

Figure 4 Walid Abu Shakra, Olive Tree on al-Baten,

1980, drypoint engraving, edition 22/75, 34.5 x 39 cm.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

On November, 15th 1988, the Republic of Algeria officially recognized the state of Palestine. Nevertheless, the hope of the Palestinians to regain their native land remains slim. Faced with the rising of the state of Israel, they bravely continued resistance actions. Yet, the crisis, which is still ongoing, goes beyond the armed conflict. Most importantly, it reflects the intention of the Palestinian population, weather in the occupied territory, or from the diaspora, to preserve the collective memory, which has to remain.

Edited by Elsie Labban

Comments on Safeguarding the Palestinian Collective Memory