In the early 20th century, Egyptian female artists used their work as part of the feminist movement. Such advocacy coincided with the anti-colonial and nationalist movements of the era. This spirit was amplified by the 1952 Egyptian revolution, in which Egyptian soldiers overturned the authoritarian royal regime, banished the British colonization of Egypt, and established a nationalized republic. Consequently, political activists, who wished to effect reform in Egypt, criticized and aimed to dissolve the power structure that resulted in unjust living conditions for the working class and peasants. Those power structures included the aristocracy's monopoly of agricultural land, low wages, the deteriorating infrastructure in rural areas, and more.

In the spirit of reforming Egyptian society, feminists sought to address women’s rights.1They aimed for living conditions that did not restrict women's potential as human beings. Among the influential voices that fought for reform were those who used their art. The role of art in the feminist movement can be seen through the works of Inji Efflatoun (1924-1989) and Gazbia Sirry (1925-2021). In their paintings of popular-class and peasant women, Sirry and Efflatoun provided socio-political statements that acknowledged these women as Egyptian characters with a role to play in society’s reform. Simultaneously, there paintings criticized the unjust conditions that shaped women’s lives at the time.

Depicting a Marginalized Role

Understanding the roots of social conventions that restricted women's lives make us appreciate Efflatoun and Sirry's desire to address the unjust conditions. While the feminist movement in Egypt started in the late 19th century, little public presence of women continued well into the 1940s and 50s.2That was when the two artists started to become more involved in political activism and create art.

Traditionally, women performed domestic duties privately, and this work was marginalized compared to men's more public and socially celebrated role in civic and private-sector employment. 3Many restrictive social traditions limited women's ability to be present in the public sphere and exercise their citizenry rights. For instance, the social custom of veiling women's faces – from Jewish, Christian, and Muslim backgrounds – isolated women from the public sphere.4These restrictive traditions left a lasting shadow and continued to be debated by feminists until the 1952 revolution in Egypt. In the wake of the revolution, feminists strongly argued for women's rights to make political decisions, perform different jobs that would typically be assigned to men, and dismantle the social stigma of divorce. As such, in the times of Efflatoun and Sirry, Egyptian society could undoubtedly benefit from artworks that highlighted feminist issues.

Liberating the Role of Women: Mothers and Leaders

Efflatoun and Sirry’s ardent will to fight for women’s rights was perhaps inspired from childhood, as both grew up in households where maternal figures acted as leaders. Efflatoun's mother was divorced and had to earn an independent living to support her two daughters.5Early on, Efflatoun became aware of the injustices that confronted women. Her mother faced the stigma of divorce, and as a retaliation for her insistence on leaving her husband, he denied her, Efflatoun, and Gulperi (Efflatoun’s sister) the lawful alimony to survive. Similar to the rebellious character of Efflatoun’s mother, Sirry’s mother encouraged her to pursue a degree in painting at a time when it was the norm for women to join the faculty of home management in preparation for a traditional role as housewives. Sirry’s mother hid from the family that her daughter was enrolled at the Higher Institute of Fine Art for Female Teachers in Cairo.6 Again, Sirry became aware of the limited freedoms allowed to women from a young age. After the death of Sirry’s father, her mother could not live alone due to the social stigma of a single woman living alone. Therefore, Sirry's mother and her two daughters moved to their divorced grandmother’s home in el-Hilmiya al-Qadima. Needless to say, both Efflatoun and Sirry were neither raised in a traditional home nor by conventional women.

Indeed, Efflatoun and Sirry's past paved the way for their future careers as pioneers in feminist art expression. By addressing the inequalities among the social classes in Egypt, the artists sought a role that exemplified women’s potential impact in society. Efflatoun and Sirry honed their painting skills and investigated the injustices in their community. From the age of fifteen, Efflatoun’s private tutor was Kamel el-Telmissany (1915-1972), one of the representatives of the Egyptian surrealist collective art et Liberté. El-Telmissany introduced her to Marxism and the struggles of Egyptian peasants. Furthermore, Efflatoun joined the Egyptian Communist Party (ISKRA), where she was active in the Jamaliyah district, one of the popular-class districts in Cairo.7

Similarly, young Sirry was mentored by her two uncles, who were talented at painting, and shared company with artists such as Ahmed Sabry (1889-1955). Early in her artistic career, Sirry was mentored by renowned Egyptian artists such as Mahmoud Said (1897-1964) and Ragheb Ayad (1882-1982). Shortly after the Egyptian Modern Art Group (1946) was formed, Sirry joined. She became an active participant in art events and discussions that articulated the artists' visions for social reform. In this circle, she identified with the idea that the language of art could eloquently express nationalist political concerns.8 She also engaged in discussions that increased her awareness of the pressing social and political situation.

Yet, it was Efflatoun and Sirry’s visits to rural Egypt and neighborhoods of the working class that exposed them firsthand to the real struggles. During separate trips to the rural towns of Nubia and other regions in the south of Egypt, they discovered a side of Egypt they had not been familiar with.9 Both artists bore testimony to the challenging living conditions caused by years of neglect. But, in Efflatoun's words, these experiences were the "best school."10

Sirry and Efflatoun’s involvement in political life came at a cost. The goals and ideas of activists like them disagreed with the Nasserist regime's policy. In the late 1950s, the Nasserist regime made a series of arrests of leftist activists and intellectuals, among whom was Efflatoun. As a result, Efflatoun was in prison for four years from 1959-1963. Sirry was also arrested for couple of days in 1959, and her husband, Adel Thabet, was detained for three years. During these dire times, Efflatoun produced paintings expressing the cruelty of life behind bars, as seen in Efflatoun's Portrait of a Prisoner (Fig. 1).

Representing the Collective Experience of Women

Sirry and Efflatoun's involvement in political life provided them with political and social edification. This was then translated into their paintings of female citizens. Each of the artists represented women in their own unique way. While Efflatoun's paintings publicly acknowledged that women deserve citizenry rights, Sirry's recognized women as fully capable of taking on active societal roles. To create representations of popular Egyptian class and peasant women was to integrate them into the culture in such a way that they vocalized their struggles.11

Sirry's earlier paintings recognized women from the popular class as citizens in the post-1952 republic and acknowledged women's domestic or marginalized role in society. Daily domestic chores are just as crucial as professional pursuits, which were commonly attributed to men. Nonetheless, women raising children to become new and productive members of society were not given the deserved social recognition. Sirry represented popular-class women performing daily domestic activities such as mending or tailoring clothes, caring for children and cooking. In some of these portrayals, Sirry paid special attention to the emotion that accompanied the actions. She highlighted affection and devotion in the women’s facial expressions and captured their maternal affection towards their children. The paintings proclaimed that women, in fact, had been performing a commendable and underappreciated role as housewives.12

Furthermore, Sirry’s paintings affirmed women’s roles in the future of the New Republic. This was a state the Egyptian people, including Sirry, hoped the Nasserist regime would build.13 In its vision for a revitalized society, the revolution welcomed women's right to labor to contribute to the extensive efforts needed to progress in different fields.14 Sirry’s artwork captured the essence of this new perspective.15 The bold and feminine decorative motifs, such as flowers, and the shades of colors, that ranged from soft to bold, used in the depiction of clothing also amplified the tenderness of maternal care and the strength of women as fundamental to society's power. This is tangible in her painting L’institutrice, 1954 (Fig. 2). It depicts a female teacher in elaborate clothing, caring for her female students and receiving a flower from one of them. The gifting of the flower, which occupies the center of the painting, symbolizes hope for a reformed society. As a working woman, the teacher refers to women’s roles in post-1952 Egypt. The representation of young girls as students asserts women's rights to receive an education. Sirry's paintings argued for a new way of seeing and knowing women.

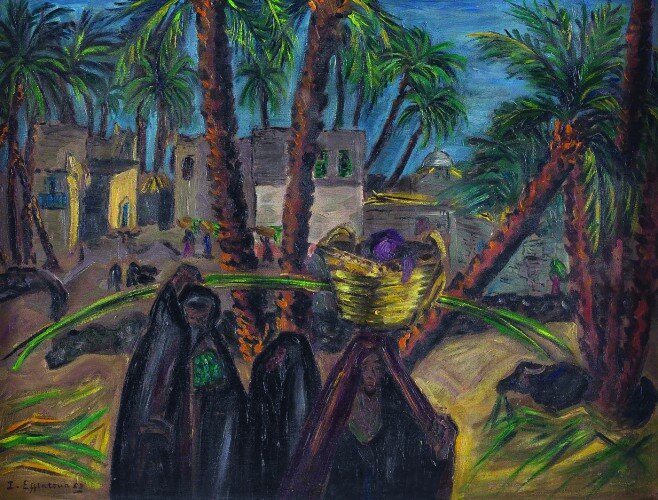

Efflatoun had a similar vision of female recognition depicted in her artwork. In the 1950s, she created paintings of working-class women, including peasants, to critique the challenging living conditions that denied them a dignified life. For instance, Farm, 1953 (Ezba) (Fig. 3) depicts a suffering countryside. At the front center, there are three women, one of whom skillfully carries a large basket on her head. There is a sense of arduous physical labor rendered through the emphasis on the large size of the basket juxtaposing the smaller size of the woman’s head. Also, Efflatoun highlighted the struggles of the working class in general and emphasized physical movement to express the labor-intensive nature of the work as in Construction Workers, 1950 (Fig.4).

These socio-political statements are further illustrated in Efflatoun’s Collecting Luffas, 1966 (Fig.5). The element of authentic culture is tangible through her depiction of female farmers. They are each adorned with a unique flowery jalabiya – a traditional dress with long sleeves. Efflatoun portrays a faithful picture of the rural Egyptian harvesting season. The painting is amassed with golden yellow piles of cornstalks left aside post-harvest. Atop the piles sit colorful women, painted with rounded shapes, representing their back-breaking laborious work while celebrating their femininity. Women in rural areas did not have a means of improving their lives since social restrictions did not allow them to receive an education. Efflatoun's empathy towards the female societal struggle can be strongly felt in her attention to detail.

Painting the Under-Represented Culture of Non-Elite Women

Undoubtedly, Efflatoun and Sirry’s paintings are an affirmation of non-elite women as Egyptian characters.16 Most members of the aristocratic class adopted a way of life that was more similar to European than Egyptian culture. Therefore, the artists used symbols from authentic Egyptian culture to create a representation of women that is both feminist and decolonized.17 This authentic culture came from rural and popular-class areas, which were not influenced by European colonial cultures, and did not have economic advantages.

In Efflatoun’s Collecting Luffas (Fig. 5), authentic culture is tangible through the women’s traditional attire, their veiled heads, and the dark crimson land being toiled. Sirry, on the other hand, had a more colorful approach; she developed an eloquent expression by representing women in their diverse, popular-class clothing. Her female figures were portrayed in modest domestic interiors, creating "mosaic-like" renditions of life scenes, described as "ornamentation" and "decorative realism."18Sirry also used color and a contrast of size to highlight the marginalized role of women in the upbringing of a new society. The colors in L’instructrice (Fig. 2) are warm to express the female teacher's affection towards the young girls. Sirry uses a juxtaposition of size to further elevate the emotion being reflected while simultaneously praising the efforts of a selfless working and nurturing woman. The scale of the female teacher exceeds that of her students. This could be seen as an allegorical reflection of the substantial role women play in the upbringing of society.

Efflatoun and Sirry defied the rules of their elitist social class and the traditions that restricted women's lives while seeking to deliver an urgent message in their time. Today, Sirry's women are unveiled from traditional social restrictions and the shadow of lack of recognition. Efflatoun's renditions of the unjust working conditions of past women are immortalized on canvas. Both depictions have enabled an object-oriented narration of Egyptian and Arab history. In terms of legacy, Efflatoun and Sirry have offered art that is an integral part of Egyptian cultural memory while serving as transnational role models for generations of women to follow.

Edited by Elsie Labban

Comments on Women Seeing Women