Egyptian artist Mahmoud Said was born into Alexandrian high society in 1897 and grew up with the privileges and constraints of a young aristocrat. His father, Mohamed Said Pasha (1863-1928), served...

MAHMOUD SAID, Egypt (1897 - 1964)

Bio

Written by ARTHUR DEBSI

Egyptian artist Mahmoud Said was born into Alexandrian high society in 1897 and grew up with the privileges and constraints of a young aristocrat. His father, Mohamed Said Pasha (1863-1928), served as Egypt’s Prime Minister from 1910 and 1914, during which time Mahmoud Said received a high-quality education at the most prestigious schools of the country. At the same time, he was privately tutored in foreign languages, music, and the visual arts. In these private art classes, he demonstrated a talent for drawing, and subsequently studied under the tutelage of the Italian painter Amelia Daforno Casonato (1878-1969) and attended the atelier of Arturo Zanieri (1870-1955). He was unable to continue his education at the School of Fine Arts; however, as his upper-class, politically influential family expected him to choose a career more appropriate to their social stratum. Consequently, he graduated from Cairo’s French Law School in 1919.

Though he had acquiesced to his family’s educational demands, Said continued to study art, spending each summer from 1919 to 1921 in Europe. He attended several summer programs in Paris, including free workshops at the untraditional Académie de La Grande Chaumière, and pursued his training at the Académie Julian. During these stays, he took advantage of the opportunity to explore the art of other European countries, visiting museums, historical monuments, and churches in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Italy. He was especially impressed by the technical mastery of artists of the Venetian Renaissance, such as Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516) and Vittore Carpaccio (1465-1520), and the rich, somber color palette used by the 15th century Netherlandish painters dubbed the “Flemish Primitives.” Back in Egypt, the artist relegated painting to a hobby in order to focus on his legal career. He was appointed judge at the Mixed Courts of Mansoura in 1927 and then in Alexandria in 1929. In 1947, he decided to change careers and dedicate the rest of his life to professional artmaking.

The art of Mahmoud Said defies quick definition, shaped by a multifaceted combination of artistic sources and experiences that impacted his personal and professional life. Born and bred amongst Cairo’s political elite, Said found himself torn between the expectations of his high social position and his strong desire to create, and this inner struggle haunted him throughout his early career. His work of the 1920s reflects an attempt to merge his love of art with his social milieu, depicting the cultured, cosmopolitan society of Alexandria’s upper crust through oil portraits of himself, his peers, and his family. The reputable characters of these canvases sport neat haircuts, elegant clothes, and precious jewels that all recall European, rather than Egyptian, fashion trends, bearing witness to the Western-facing ethos of wealthy Alexandrians during the first half of the twentieth century. The artist often portrayed them posing in interiors decorated with paintings and beautiful furniture, indicating their high social standing and privileged lifestyle. Sitting formally, even rigidly, on their chairs, these people – who were mostly the commissioners – embody the Westernized upper class that the British protectorate sought to cultivate in Egypt, providing a window onto colonial culture.

As Said’s artistic practice matured, he ventured away from his own surroundings and began to paint portraits of poor and working-class people. Specifically, he focused on the figure of the fallaha, or female peasant-farmer, which he considered to be the incarnation of pure beauty. He was not alone in this fixation; as Egyptian and Arab nationalism crescendoed over the first half of the twentieth century, artists began to look for symbols of an “authentic Egyptianness.” Much of this “authenticity” was found in images from ancient Egypt, an interest for which was fueled by a growing number of European archaeological expeditions in Egypt’s pyramids –most notably the 1922 excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings by the archeologist Howard Carter (1874-1939). The ancient remains of the advanced Egyptian civilization fascinated artists and intellectuals, who discovered an aesthetic spirit that was neither Islamic nor Arab but distinctly Egyptian.

A 1938 portrait entitled Fille à l’Imprimé, or “Girl in a Printed Dress”, shows an interesting interpretation of authentic Egyptian identity. The painting shows a dark-skinned woman, outfitted in a floral dress and a black veil, apparently taking a rest in the countryside. The woman leans her elbow against a large terra cotta jar and rests her head in her hand, staring towards the bottom right-hand corner of the painting as though lost in contemplation or averting her gaze from the viewer. In the background, dark clouds gather over the river, where a woman in a traditional abaya and a long veil is fetching some water. The portrait, titled Fallaha au Voile Noir before the artist changed its name, is not a typical image of a fallaha at all. She wears a modern, Western-style dress and earrings, and even her veil sits high on her head and leaves her neck exposed; indeed, a viewer could easily misdate the painting at first glance, thinking it depicts a woman in the latter half of the twentieth century. Where, in most Egyptian modern art, the fallaha represents a timeless Egypt uncorrupted by colonialism, Said’s choice of subject shows a more modern incarnation of ancient roots.

However modernized, the painting nevertheless shows explicit references to the Egyptian past. Defying the classical norms of European culture, his stylized portrait reflects the aesthetic standards of Amarna art, notably the bas-reliefs produced under the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaton in the 14th

century BC. A pointed chin, a flat nose, full lips, large hands, and heavy-lidded, kohl-lined eyes are all features of Said’s portrait that adhere to Amarna style conceptions of beauty. Furthermore, his sitter’s dark complexion and facial features suggest her Nubian ancestry, which is significant in the context of Said’s oeuvre. The Egyptian ruling class, including Said’s family, were mainly of Turkish or Circassian origin during this period, and his earlier portraits accordingly show people with lighter skin and facial features more akin to Europeans than to Africans. In highlighting the African roots of a subject in conversation with Amarna stylistic choices, Said suggests that Nubians are also heir to the heritage of ancient Egypt, and perhaps even represent it more “authentically” than the Westernized upper class.

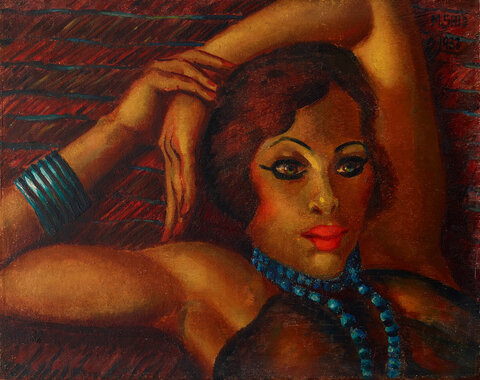

The rich oeuvre of Mahmoud Said includes an important portion of female nudes, realized from live models in a small apartment he kept specifically for the purpose. Due to his social standing, he could not receive these models in his rooftop atelier, located as it was in the home he shared with his wife and daughter. He thus kept a garçonnière in a different building, where he could execute nude paintings without scandalizing his community.

The class differences evident in Said’s portraiture also shaped the artist’s methods. The women who posed for Said’s paintings were probably prostitutes, and Said represents them in ways that differ starkly from his paintings of their aristocratic contemporaries. In nudes such as L’Endormie, or The Dreamer, completed in 1933, women appear in dynamic, relaxed poses, appearing unashamed by their exposed bodies. The works emphasize the erotic overtones of the subject matter by amplifying certain anatomical qualities, using light to intensify the curves of breasts, waists, and hips. Said’s use of light makes his subjects nearly glow, inviting the viewer to appreciate these somewhat voyeuristic images.

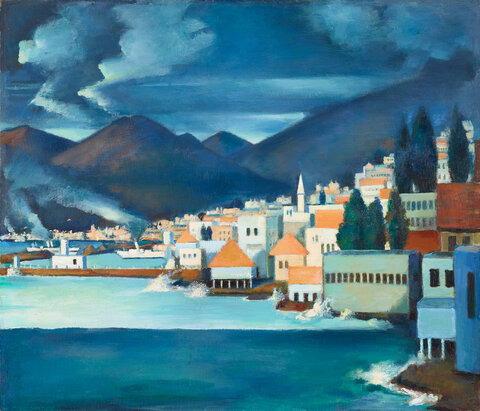

As the artist grew old, he found he could no longer sustain his career in law. The “While working in the courts I always had the sense that I was bound with shackles,” the artist observed later in life. “I wanted so much to escape from these shackles into the free world.”[1] Escape he did: in 1947, he retired from his position as a judge and began painting full-time. Although he had undeniably mastered conventional techniques, he progressively took stylistic liberties, especially in his images of landscapes in Egypt and throughout the Mediterranean. He celebrated the Nile, perfectly rendering the coastal atmosphere of the cities like Alexandria or Alamein. Like many members of the upper class, Said fled the heat of the Egyptian summer and stayed in a secondary home in Lebanon, where the small country’s remarkable topographical diversity in regions such as Mount Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley became a source of inspiration for twenty works.

Mahmoud Said questioned the principle of building a rationally structured scenery, called in Arabic Intizam al-Manzar, highly appreciated by the colonialist public. In other words, his natural scenes maintained their realistic structure. However, he surpassed the accurate representation in the treatment of some of his painting’s elements by inserting a breath of imagination and originality. Hence, he explored the duality of portraying the reality of what he observed and constructing the composition according to his own sensitivity. Painted in 1954, Le Port de Beyrouth is an example of those works where he established a specific aesthetics and technique. He used the traditional aerial perspective, which consists of creating depth with color gradation. Nevertheless, he arranged complementary colors such as orange and green and superimposed them to render the effect of his aerial perspective. Besides, he stylized the motifs of the architecture elements or the environment by reducing them to simple – nearly abstracted – forms where the light designs the diagonals and the straight lines. These recurrent manipulations of colors and almost abstract forms directed Said’s sceneries to appear idealized, reaching by that a mystical dimension: they are serene, imperturbable as if they are unaffected by the passing of time. These subtle maneuvers were the first step for Said towards a modern post-colonial style of painting: he began here to blur the visual codes for the public of his time.

As the Egyptian writer and poet Ahmed Rassem (1895-1958) has asserted, the Alexandrian painter was more interested in exploring the properties of light than he was in producing stereotyped views of the pyramids or folkloric images from the Cairo souk. In his work, Said aimed to evoke the spiritual dimension of cultural heritage by imbuing his scenes with a luminous glow. “What I’m looking for is radiance rather than light,” the artist explained in 1927. “What I want is internal light, not surface light.”[2] His paintings attest to his fascination with the reflection of the light on Egyptian landscapes, as well as the intensity of the color such light produced. This can be observed in Le Bain des Chevaux à Rosette (1950), in which two naked men bathe their horses in a river next to the northern port city of Rosetta while villagers embark on the central sailboat. Here, the artist captures this exact moment when the rain stops and the first beams of the sun pierce the clouds, creating a soft, silvery light that contrasts the blue cobalt of the sky and the water with the white on the sails as well as the skin of the animals. The sea itself seems like a source of light, as its waves absorb and reflect it in endless variations.

Mahmoud Said created a harmonious world that stretched conventional paradigms of representation to their limits and imbued standard depictions with magic, a practice that confused the audience of that time and marked the transition from a colonial to a post-colonial art-making. A witness to the political upheaval of his time, he subtly revived the representational traditions of ancient Egypt and wove them into modern portraits, suggesting the immortal, eternal glory of the land.

Mahmoud Said died in 1964, survived by a prolific and innovative oeuvre.

[1] Interview of Mahmoud Said by Mostafa Suef reported in Didier-Hess, Valerie, and Hussam Rashwan.Mahmoud Said, Catalogue Raisonné, Volume 1, Paintings. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2015. [P.654]

[2] Mahmoud Said, letter to Pierre-Beppi Martin, 1927 translated from French in Didier-Hess, Valerie, and Hussam Rashwan. Mahmoud Said, Catalogue Raisonné. Volume 2, Drawings. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2015.[P.133]

Sources

Abaza, Mona, and Sherwet Shafei. Twentieth-Century Egyptian Art: the Private Collection of Sherwet Shafei. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press, 2011.

Bardaouil, Sam, and Fellrath, Till. Art Et Liberté, Rupture, Guerre Et Surréalisme En Égypte (1938-1948),[Exhibition Catalogue, ‘Art Et Liberté, Rupture, Guerre Et Surréalisme En Égypte (1938-1948)’. Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, October 19th 2016 – January 16th 2017]. Paris, France: Skira, 2016.

Didier-Hess, Valerie, and Hussam Rashwan. Mahmoud Said, Catalogue Raisonné. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2015.

Eigner, Saeb. Art of the Middle-East, Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran. London, UK: Merell Publishers Limited, 2011.

Gershoni, Israel. “The Evolution of National Culture in Modern Egypt: Intellectual Formation and Social Diffusion, 1892-1945.” In Poetics Today 13, no. 2 (1992): 325. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1772536?seq=1.

Karnouk, Liliane. Modern Egyptian Art, 1920-2003. Cairo, New York, Egypt, USA: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005.

Lenssen, Anneka, A. Rogers, Sarah, and Shabout, Nada. Modern Art in the Arab World, Primary Documents. New York, USA: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

Radwan, Nadia. “Between Diana and Isis: Egypt’s ‘Renaissance’ and the Neo-Pharaonic Style (1920s‒1930s).” in Perrin, Emmanuel (Dir.), Dialogues artistiques avec les passes de l’Égypte: une perspective transnationale et transmédiale, Paris, InVisu (CNRS-INHA), 2017. Dialogues Artistiques Avec Les Passés De L'Égypte, 2017. https://books.openedition.org/inha/7194#text.

Samah, Selim. “The New Pharaonism: Nationalist Thought and the Egyptian Village Novel, 1967-1977.” in the Arab Studies Institute, vol.8/9, n°2 (2000). https://www.jstor.org/journal/arabstudij.

Zhao, Zhenxiao. “The Time Period and Artistic Style of Amarna Art.” in American Journal of Art and Design. Science Publishing Group, December 30, 2016. http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/journal/paperinfo?journalid=106&doi=10.11648/j.ajad.20160101.11.

Seggerman, Alexandra Dika. Mahmoud Said. Accessed December 12, 2019. http://www.encyclopedia.mathaf.org.qa/en/bios/Pages/Mahmoud-Said.aspx.

about Mahmoud Saïd. Accessed December 12, 2019. http://www.mahmoud-said.com/aboutMS.html.

CV

Selected Solo Exhibitions

1991

Mahmoud Said Museum, Alexandria, Egypt

1982

Mahmoud Said, Embassy of the Arab Republic of Egypt, Tel Aviv, Occupied Palestine

1964

Retrospective exhibition of the works of the award-winning painter Mahmoud Saïd 1897-1964 (On the occasion of the Twelfth Anniversary of the Revolution), Musée des Beaux-Arts and Cultural Centre, Alexandria, Egypt

1960

Retrospective exhibition of the works of the award-winning painter Mahmoud Saïd (On the occasion of the Eighth Anniversary of the Revolution), Museum of Fine Arts and Cultural Center, Alexandria, Egypt

1951

Retrospective des oeuvres de Mahmoud Said, 1921-1951, Grand Palace of the Royal Society of Agriculture, Guézireh, Egypt

1942

First retrospective exhibition of Mahmoud Saïd, Atelier d’Alexandrie, Alexandria, Egypt

1918

Exhibits for the first time at the Salon de la Municipalité, Alexandria, Egypt

Selected Group Exhibitions

2024

Arab Presences: Modern Art And Decolonisation: Paris 1908-1988, Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France

2023

Beirut And The Golden Sixties: A Manifesto Of Fragility, Mathaf, Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920-1960, Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University Harlem, New York, USA

2022

The Egyptian Art in the Twenties of the Last Century, Centre des Arts, Aisha Fahmy Palace, Cairo, Egypt

Manifesto of Fragility: Beirut and The Golden Sixties, Lyon Museum of Contemporary Art, Lyon, France

2021

The Nude: Sexuality, Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

2018

Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948), Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom

2017

Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948), Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany

Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948), Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain

100 Chefs-d’oeuvre de l’art moderne et contemporain arabe, La Collection Barjeel, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, France

2016

Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948), Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

2015

The Barjeel Foundation: Debating Modernism, Whitechapel, London, United Kingdom

2014

Sky Over the East: Works from the Collection of Barjeel Art Foundation International Museum Day 2014, Emirates Palace, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

2012

A Century of Egyptian Art, Al-Ahram Arts Centre, Cairo, Egypt

Le Corps découvert, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, France

2010

Opening the Doors: Collecting Middle Eastern Art, Emirates Palace, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

AC&C Art Fund Collection, SOD-IC Sales Centre, Cairo, Egypt

2002

Egyptian Pioneer Artists (Inaugural Exhibition), Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Alexandria, Egypt

c.1966 L’Exposition des Artistes Alexandrins en Espagne, Musée des Beaux-Arts and Centre Culturel, Alexandria, Egypt

1952

The 26th Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy

1950

The 25th Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy

1949

Égypte-France, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Pavilon Marsan, Paris, France

Six Egyptian Artists: Mahmoud Said, Mohammed Naghi, Mohammed Hassen, Youssef Kamel, Sanad Basta, Dora Khayatt, The British Institute, Cairo, Egypt

1948

The 24th Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy

Peintres des Pays Arabes, Palais UNESCO, Beirut, Lebanon

Exposition de l’Atelier, Alexandria, Egypt

1947

International Exhibition for Fine Contemporary Art, Guézireh Exhibition Grounds, Cairo, Egypt

1945

XXVème Salon du Caire, Guézireh Grand Palace of the Royal Society of Agriculture, Cairo, Egypt

1942

Troisième Exposition de l’Art indépendant, Hôtel Continental, Cairo, Egypt

1940

XXème Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

Première Exposition de l’Art Indépendant, Nile Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

1939

XIXème Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

Exposition des Oeuvres destinées au Musée de Suez, Museum of Modern Art, Cairo, Egypt

1938

The 21st Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy

XVIIème

Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

1937

Exposition international des arts et techniques dans la vie moderne, The Egyptian Pavilion, Paris, France

Studio Guild, New York, United States of America

1936

XVIème Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

Architectural League (Grille Room), New York, United States of America

1935

XVème Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

1934

XIVème Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

1933

XIIIème Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

1932

XIIème Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

Salon de Peinture d’Alexandrie, Palais Zogheb, Alexandria, Egypt

1931

Le Salon d’Alexandrie, Palais Zogheb, Alexandria, Egypt

XIème

Salon du Caire, Palais Tigrane, Cairo, Egypt

1929

Salon de La Chimère, Cairo, Egypt

Salon du Caire, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Cairo, Egypt

1928

Salon des Amis de l’Art, Palais Tigrane, Cairo, Egypt

1927

Premier Salon de La Chimère, Roger Breval’s studio, Cairo, Egypt

1925

Exhibition with Mohamed Naghi, Roger Bréval & Charles Boeglin, Roger Breval's studio, Cairo, Egypt

Awards and Honors

1960

The State Appreciation Award in Arts, from President Nasser, Egypt

Collections

Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

Mahmoud Said Museum, Alexandria, Egypt

The Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

The Museum of Modern Egyptian Art, Cairo, Egypt

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

Press

لوحات استثنائية للفنان المصري محمود سعيد في كريستيز بدبي

sputniknews.com, Arabic, 2018

هو أحد الرواد الذين وضعوا أسس الفن التشكيلي

Al-hakawati.net, Arabic, 2019

Exhibition in the memory of painter Mahmoud Said

Nayera Yasser

Daily News Egypt, English, 2018

Mahmoud Said: An Artist that Revolutionized Modern Egyptian Art

Lamiz.com, English, 2017

The first international encyclopaedia exclusively focused on the works of the pioneering Arab artist, Egyptian painter Mahmoud Said (1897-1964)

Mohamed Salmawy

weekly.ahram.org.eg, English, 2017

Chronicling the life and work of Egyptian artist Mahmoud Said

Thenational.ae, English, 2017

Sotheby's to Sell Group of Important Paintings by Mahmoud Said

Artdaily.com, English, 2017

Sotheby’s London will be auctioning off Mahmoud Saïd’s Portrait de Madame Batanouni Bey, 1923, for bids beginning at £150 000

en.vogue.me, English, 2017

Understanding the art of Mahmoud Said

alarabiya.net, English, 2017

Safarkhan gallery remembers Egypt's iconic painter Mahmoud Said

Ahram.org.eg, English, 2018

The permanent revolution_ From Cairo to Paris with the Egyptian surrealists MadaMasr.pdf

Exhibitions

MAHMOUD SAID Artwork

Become a Member

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Welcome to the Dalloul Art Foundation

Thank you for joining our community

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

-Front.jpg)

-Front.jpg)