Written by Arthur Debsi Born in Damascus in 1923, Mahmoud ibn Amin Hammad grew up when Syria had been under the French mandate for three years. He started his education at the Italian School of...

MAHMOUD HAMMAD, Syria (1923 - 1988)

Bio

Written by Arthur Debsi

Born in Damascus in 1923, Mahmoud ibn Amin Hammad grew up when Syria had been under the French mandate for three years. He started his education at the Italian School of Damascus, before enrolling at the Jawdat al-Hashemi secondary school. Hammad showed an early interest, as well as a talent, for art, and was encouraged by his teachers to continue on this path.

Mahmoud Hammad’s education was linked to Italy since the country established a special relationship with Syria as of the 1930s. When Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) took power in Italy in 1922, he wanted to restore the former glory of the Roman Empire, including the territories around the Mediterranean Sea[1]. Fascist Italy also aimed to reinforce its military influence in the region of the Levant against France, which was occupying Syria, and Lebanon back then. During the 1930s, the Italian government demonstrated support for the nationalist movements occurring in Syria, especially through culture. Some Syrian students including Mahmoud Jalal (1911-1975), and Salah Nashif (1914-1971), benefited from a scholarship from Mussolini’s government to study art in Italy[2]. Hammad traveled to Italy in 1939 for the first time, but had to come back to Syria because of the outbreak of the WWII, taking with him memories of the Italian paintings, that he had contemplated.

The period of the 1940s was a significant time, when the cultural, and artistic scene began to develop in Syria. After studying in Europe, the Syrian art students played a key role in this development, starting with the creation of an artists’ community. Back from Italy to Damascus, Mahmoud Hammad became an important figure of the local artistic dynamic. In 1940, he exhibited with some Syrian, and French artists, at the first group exhibition of its kind, held at the Law Institute of Damascus. There, he encountered Nasser Chaura (1920-1992), with whom he established the Atelier Veronese in 1941, in reference to the Italian painter Paolo Veronese (1528-1588). This was an art space, which mainly attracted artists from all around the country, and even from countries like Egypt, and Iraq. Furthermore, it was also a cultural place, where writers, and journalists would gather, and debate. Due to an absence of artistic hubs, the activities occurring at the Atelier Veronese were necessary for Syrian artists to find their artistic orientation, as Hammad remembered: ‘We were disoriented amidst the chaos of experimentation, seeking knowledge through rare art books and magazines and a handful of exhibitions in Damascus (…)’[3].

In 1953, Mahmoud Hammad traveled again to Italy, but this time on a scholarship like his predecessors, and studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome. In the Italian capital city, he followed a quality curriculum, which included painting, medal engraving, printmaking and mural art courses. In parallel, Hammad was exposed to the rich, and important cultural landscape of the country, discovering the artworks of great masters. In 1957, he returned to Syria, and was appointed art teacher in the city of Daraa, in the south-west region. In 1960, he relocated to Damascus, and contributed to the foundation of the first Faculty of Fine Art of Damascus University[4]. In 1965, alongside with Elias Zayat (1935-), and Nasser Chaura (1920-1992), Mahmoud Hammad formed the Damascus Group, also known as ‘Group D’. The artists raised, and encouraged debates on art theories, especially abstraction; while supporting the relationships between the artists. Even if this was for a short duration, the initiatives of the Damascus Group were important, since it compensated for the lack of publications, as well as art critics in the country[5]. In 1967, Hammad received a grant from UNESCO, which enabled him to go back to Europe, where he stayed few months between Rome, and Paris. Back in Syria, he became dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Damascus University until 1980.

The primary stage of Hammad’s career is related to Impressionism, which was actually the first Western art movement to be introduced in Syria, under the Ottoman occupation. At that time, some Syrian soldier-painters were sent to Paris, like Tawfiq Tariq (1875-1945) to complete their studies in art, discovering easel painting[6]. Under the French mandate from 1920 to 1946, many artists such as Maurice Denis (1870-1943), and Jean-Charles Duval (1880-1963) went to Syria, where they took inspiration from the local cities, and landscapes for their paintings. On the other hand, the country had some Syrian artists like Michel Kursheh (1900-1973), who traveled on scholarships to Europe, where they studied easel painting, and Impressionist technique. These cultural exchanges, and contacts between France, and Syria paved the ground of the first artistic activities, and events. In his early paintings from the 1940s, Mahmoud Hammad adopted Impressionism through a series of works illustrating streets, still-lives, and views over the Syrian landscapes. He however chose Realism, when he portrayed ordinary people, either coming from the city, or the countryside. Hammad’s artistic tendencies were also influenced by the artists, who had returned from Italy like the sculptor Mahmoud Jalal (v1911-1975), and Salah al-Nashif (1914-1971). Yet, it was in Italy, where he pursed, and actively improved his work on Impressionism.

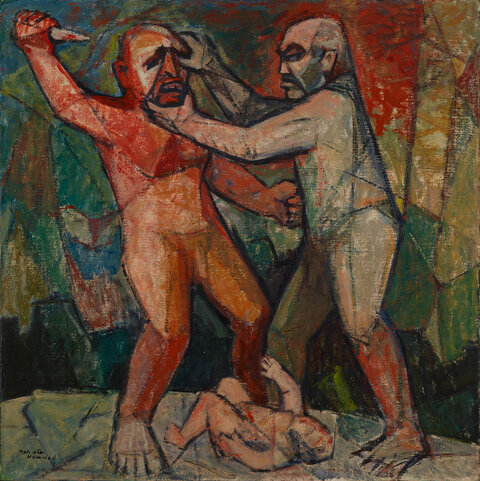

In 1958, the Syrian Ministry of Culture was formed, and gave Mahmoud Hammad the mission to rediscover, promote, and preserve the archeological heritage, and sites of the country[7]. Part of the cultural policies, reviving the past was also a way to celebrate the historical grandeur of Syria. Hammad lived in Daraa at that time, and got interested in the rich archeological heritage of Horan. This region located in Southwestern Syria, has been a historical land for millennia, where several ancient civilizations succeeded. Progressively detaching himself from academic art, Hammad tried to find his artistic language, and took inspiration from these surroundings, in which he was immersed for two years. The shift towards abstraction in his oeuvre, is seen in many of his works such as Cain & Abel (1958), part of the Dalloul Art Foundation’s collection. Here, he illustrated a major episode of the Book of Genesis, in which Cain, the older son of Adam, and Eve, killed his younger brother Abel, out of anger, and jealousy. Following the biblical narrative, Mahmoud Hammad depicted the time of the fight – like a mural painting –, when Cain is about to stab Abel, who tries to subdue him. In accordance with the iconic tradition, Cain, who symbolizes evil, violence, has a darker skin color; whereas Abel, is colored in cool colors, meaning his innocence. The religious subject stems from the classical painting, but the plastic treatment is modern. Hammad effectively employed abstract forms, that he contoured with thick black brushstrokes, seeing the drawing as geometric pieces assembled with each other. Throughout this technique, he also demonstrated his mastery of sculpting, as he gave a sort of sculptural aspect to the characters. The painting could refer to the historical context, which transformed the Arab world. In 1958, the political union between Syria, and Egypt was established as the United Arab Republic, aiming to unify the Arab countries under pan-Arab values. However, the creation of this State provoked many tensions, and internal conflicts between the countries, with the tendency of Egypt to impose its political hegemony. Hammad might have illustrated these tensions, drawing a parallel between the two brothers, and the two brotherly countries.

Mahmoud Hammad is mostly known for his work on abstraction, which he adopted from 1964 to 1988. In late 1964, the Italian painter Guido La Regina (1909-1995) was appointed technical expert on the painting staff at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Damascus University. For three years, La Regina proposed a methodology to the local artists, which was highly related to the international modern art trends, and more specifically to abstract art. Hammad was enthusiastic about this methodology, that he considered to be important for the development of the modern art movement in Syria[8], as well as art education. Indeed, it was primordial for modern Syrian artists – and more generally Arab artists, to free from Western culture, and academism, in which they were conditioned. Abstraction was consequently an approach, which corresponded to their own artistic identity. In this search for authenticity, Mahmoud Hammad decided to exploit the Arabic calligraphy, as a historical specificity to Islamic arts. In the Islamic artistic tradition, the script has a sacred dimension because it is initially considered to be the materialization of the Divine Word, contained in the Quran.

Part of the Dalloul Art Foundation’s collection, a series of paintings executed by Mahmoud Hammad, reveals his experimentation on both abstraction, and Arabic letters, whose the combination is called ‘abstract calligraphy’[9]. In the example entitled Salam Kawlan Min Rab Raheem (1987), from a series of forty-four paintings with the same title; the artist transcribed the 58th verse of the surah Ya Sin from the Quran, which means ‘Peace, a Word from Merciful God’. But though he referred to the Muslim religion, Hammad showed that he was more interested in the shapes of the letters themselves, than the religious statement. Applying a harmonious palette of warm colors, and contrasting the hues; he distorted, and arranged the geometric letters like a construction. As matter of fact, some Arabic letters such as ‘S’, and ‘Q’ are recognizable, but the whole verse is not legible to the viewer. The painting Salam Kawlan Min Rab Raheem (1987) accurately demonstrates how Mahmoud Hammad combined the Islamic artistic culture, with modern art technique. Focusing on the visual effect, he gave the painting a high spiritual dimension, fulfilling the entire composition – like Muslim artists have always done, to ‘fills the void’[10].

In the 20th century, the oeuvre of Mahmoud Hammad is an example of how Syrian art elaborated from an academic style to an innovative plastic language. Connecting his art to the modern art movement, by employing abstract technique; Hammad also stayed true to his Islamic artistic heritage, and its rules. Throughout this approach, the artist imposed Syria as a an active place for experimental art in the Middle East.

Mahmoud Hammad passed away in 1988.

Sources

Arielli, Nir. Fascist Italy and the Middle East, 1933-40. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Ali, Wijdan. Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida, 1997.

Atassi, Mouna, and Samir Sayegh. Contemporary Art in Syria, 1898-1998. Damascus, Syria: Gallery Atassi, 1998.

Eigner, Saeb. Art of the Middle-East, Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran. London, UK: Merell Publishers Limited, 2011.

Forlin, Olivier. “Le Fascisme Et La Méditerranée Arabo-Musulmane Dans Les années 1930.” Cahiers De La Méditerranée, 2018. Accessed December 21, 2020. http://journals.openedition.or... .

Hammad, Lubna. ‘A History of Art Associations in Damascus During the 20th Century: From Emergence Until the First Arab Conference of Fine Arts in Damascus in 1971.’ Translated by Basel Jbaily. Atassi Foundation. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.atassifoundation.com/features/a-history-of-art-associations-in-damascus-during-the-20th-century-from-emergence-until-the-first-arab-conference-of-fine-arts-in-damascus-in-1971.

Leaman, Oliver. Islamic Aesthetics: An Introduction. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2004.

Lenssen, Anneka. 'The Plasticity of the Syrian Avant-Garde, 1964-1970', ARTMargins, 2:2 (June, 2013), Pp. 43-70. © 2013 by ARTMargins and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2013.

Lenssen, Anneka, A. Rogers, Sarah, and Shabout, Nada. Modern Art in the Arab World, Primary Documents. New York, USA: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

Mahmoud Hammad. Accessed December 10, 2020. http://www.mahmoudhammad.com/.

Mikdadi, Salwa, and Donald Kunze. Elias Zayat: Cities and Legends. Milano, Italy: Skira, 2017.

Rasmussen, Jack. (2007). Art From Syria, A Journey through Half a Century of Creativity. [Exhibition Catalogue, ‘Art from Syria, A Journey through Half a Century of Creativity’. Washington D.C., The Katzen Arts Center, June 5th – June 17th 2007]. Washington D.C., USA: The Embassy of Syria - The Katzen Arts Center at The American University Museum, 2007.

Shabout, Nada. Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida, 2015.

Yazeji, Rana, and Reem Al Khateeb. “Compendium Country Profile Cultural Policies in Syria,” 2014. https://www.culturalpolicies.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/syria_full_profile_2014.pdf.

[1] Forlin, Olivier. “Le Fascisme Et La Méditerranée Arabo-Musulmane Dans Les années 1930.” Cahiers De La Méditerranée, 2018. Accessed December 21, 2020. http://journals.openedition.or.... [P.1]

[2] Ali, Wijdan. Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida, 1997. [P.89]

[3] Mahmoud Hammad in 1984 during a cultural seminar ‘Youth and Visual Art’, quoted in Hammad, Lubna. ‘A History of Art Associations in Damascus During the 20th Century: From Emergence Until the First Arab Conference of Fine Arts in Damascus in 1971.’ Translated by Basel Jbaily. Atassi Foundation. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.atassifoundation.com/features/a-history-of-art-associations-in-damascus-during-the-20th-century-from-emergence-until-the-first-arab-conference-of-fine-arts-in-damascus-in-1971.

[4] In collaboration with the Faculty of Fine Arts in Alexandria, the Higher Institute of Fine Arts in Damascus was founded in 1960, prior to become the Faculty of Fine Arts, three years later.

[5] Mikdadi, Salwa, and Donald Kunze. Elias Zayat: Cities and Legends. Milano, Italy: Skira, 2017. [P.12]

[6] Ali, Wijdan. Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida, 1997. [P.87]

[7] Yazeji, Rana, and Reem Al Khateeb. “Compendium Country Profile Cultural Policies in Syria,” 2014. https://www.culturalpolicies.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/syria_full_profile_2014.pdf. [P.16]

[8] Lenssen, Anneka. “Anneka Lenssen, 'The Plasticity of the Syrian Avant-Garde, 1964-1970', ARTMargins, 2:2 (June, 2013), Pp. 43-70. © 2013 by ARTMargins and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.,” 2013. (Online) [P.53]

[9] Ali, Wijdan. Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida, 1997. [P.170]

[10] Abdelkedir Khatibi, and Mohammed Sijelmassi quoted in Leaman, Oliver. Islamic Aesthetics: An Introduction. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2004. [P.45]

CV

Selected Solo Exhibitions

1953

Fine Arts Association, Damascus, Syria

Selected Group Exhibitions

2023

UNTITLED Abstractions, Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

2022

New Acquisitions 2010–2022, Koroska Gallery of Fine Arts, Slovenj Gradec, Slovenia

2021

Leads & Artistic Cues from the Arab World, Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

2020

Gallery for Peace, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Koroška, Gallery Slovenj Gradec, Slovenia

2018

A Century in Flux, Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Night was Paper and we were Ink, Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2017

Modern Art from the Middle East, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, United States of America

2016

Hurufiyya: Art & Identity, Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Alexandria, Egypt

The Short Century, Sharjah Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2014

Sky Over the East, Emirates Palace, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Works on Paper: Hikayat, Green Art Gallery, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

2013

Between Desert and Sea, A Selection from the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, Pera Museum, Istanbul, Turkey

1966

Exposition de Peinture Syrienne Contemporaine, Musée Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock, Beirut, Lebanon

1952

The 3rd exhibition of Fine Arts, National Museum of Damascus, Damascus, Syria

1951

Club Al Saad, Aleppo, Syria

1950

The 1st exhibition of Fine Arts, National Museum of Damascus, Damascus, Syria

1939

The Halls of the Law Institute, Damascus, Syria

Honors and Awards

1989

Syrian First Class Order of Merit

1977

Syrian Highest Medal of Merit in Arts and Literature

1975

Knight Commander Award

1950

First Prize

Affiliations and Membership

1965

The Damascus Group

1940

Syrian Art Association

Atelier Veronese

Collections

Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

The Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

The British Museum, London, United Kingdom

The Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, Amman, Jordan

The National Museum of Damascus, Damascus, Syria

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

Press

Mahmoud Hammad - Artists - The Jalanbo Collection A Private Collection of Modern & Contemporary Art from the Middle East_Press.pdf

وكالة أنباء الإمارات - Barjeel Art Foundation masterpiece on loan SharjahMahmoudHammad_ Museum of Islamic Civilisation.pdf

محمود حمّاد..الفنان الذي منح الحرف العـربي البطولة المطلقة في اللوحة - البيان.pdf

استعادة الفنان السوري محمود حماد … رائد الحروفية وضابط إيقاعها.pdf

GAG_Works+on+Paper_Hikayat_Press+Release+Green+Gallery_Page_1.pdf

ناقد ورسام تشكيلي يسرق لوحات محمود حماد من الجامعة ليشتري بيتاً الجمل بما حمل نضع أخبار العى aljaml.com.pdf

محمود حماد رسام الكلمات التي تشف عن زوالها بقلم-فاروق يوسف.pdf

محمود حماد...موسيقا لونية إنسانية.pdf

eSyria.pdf

محمود حمّاد..الفنان الذي منح الحرف العـربي البطولة المطلقة في اللوحة.pdf

الباحثون السوريون - تجريدٌ سوريّ.. الفنان محمود حماد.pdf

MAHMOUD HAMMAD Artwork

Become a Member

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Welcome to the Dalloul Art Foundation

Thank you for joining our community

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies