As a matter of debate, the historical and cultural situation of Lebanon has always been attached to the idea of a bridge between two worlds: that of the West and the East, i.e. the Arab world. Many factors contributed to the construction of this narrative, which was founded on the question of civilization affiliation. The sense of belonging of the population varied particularly between Phoenician and Arab affiliations. Moreover, the religious aspect was as important to take into consideration, and correlated with the notion of identity. This perception was decried by Lebanese writer Amin Maalouf: "Séparer l’Église de l’État ne suffit plus, tout aussi important serait de séparer le religieux de l’identitaire" 1.

In the study at hand, it seems that explaining the specificity of Lebanese modernity should go hand in hand with a comparison of what was happening in the rest of the Arab countries. In its modern history, Lebanon somehow showed a disconnection – but not a detachment – with the other. Lebanese specificity seems to stem from the consensual position that the country has always tended to respect in its external and internal affairs. Politics, art, and culture highly reflect the search for the Lebanese identity as the issue of determining it was discussed: "Manquant généralement d’esprit de continuité, passant d’une période transitoire à une autre, sans souci d’expression totale et de maturité, son identité artistique [celle de l’artiste libanais] comme l’identité de son pays est difficile à déterminer"2.

Every Arab modernity distinguishes itself and interconnects with one another through its respective art. Yet, the Lebanese modernity has a somewhat relative status justified by a “sentiment particulariste”[3]. For instance, art practice was integrated quite late in the Lebanese public education system as the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA) opened in 1937, in Beirut 4. The need to form a young generation of artists did not seem to be part of the colonial process under the French mandate (1920-1943), as had been the case in some North African countries. Compared to Iraqi and Egyptian, the Lebanese students began their formal training in Europe. Such people included César Gemayel (1898-1958) and Moustafa Farroukh (1901-1957) during their studies in the 1920s. When they came back to Lebanon, they introduced the European artistic style as seen in Portrait of a Woman from the South (Fatima) (1940) by Farroukh (fig. 1).

Figure 1 Moustafa Farroukh, Portrait of a Woman from

the South (Fatima), 1940. Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 42 cm.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

Even till today, Lebanon continues to face an identity crisis with the difficulty to find an asserted national consciousness. In addition to a richness it possessed, the multi-confessional Lebanese society is also a source of divergence between the different communities, as the outbreak of the Civil War in 1975 demonstrated. Breaking off social cohesion, the 15-year conflict proved the complexity of defining what it means to be ‘Lebanese’.

Cultivating Originality

Particularly known to be an Arab nationalist figure, Syrian art historian Afif Bahnassi (1928-2017) argued that having educated Lebanese students in Europe was a way to acculturate and keep them distant from their Arab roots 5.

The counter-argument is that Lebanon had always maintained a positive and long-term connection with the Western world. Furthermore, the European presence in the country was not fundamentally viewed by Lebanese people as an oppressive power. On the contrary, Western culture and especially the French one, was well integrated by a large part of the population completely unaffiliated with the Arab culture. There is no doubt that the historical and influential establishment of the Christian community – which cannot be defined as a minority religion – participated in this integration 6.

In the arts, many practices could exemplify how this specific outlook towards Western culture took shape. Examples would be figurative painting inherited from the Christian iconography tradition, and the production of nude paintings as well. In the 1920s and 1930s, Lebanese art students from the first generation were open to the latter genre they discovered when in Europe. Consequently, the early production of nudes was not only limited to sketches, but was also adopted as a form of art of itself in Lebanon as seen in the painting Nude in Repose (fig.2) (non-dated) by César Gemayel (1898-1958). The depiction and the exhibition of painted naked bodies were also slightly more accepted by the audience than in other Arab countries. The teaching of human anatomy was provided through the use of fully dressed models in Iraq, while in Egypt, the question of sexuality was progressively passing through the collimator of the growing Islamist wave.

Figure 2 César Gemayel, Nude in Repose, non-dated, oil on canvas, 46 x 64 cm.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

Another originality of the Lebanese artistic modernity, which should be highlighted, is the development of the movement itself. Lebanese artist Helen Khal (1923-2009) claimed: "L’artiste libanais aime être individualiste et ne croit pas à la mentalité régionaliste (iqlimi)" 7. In comparison with other artistic initiatives in the 1950s and 1960s in the Arab world – the Group of Baghdad for Modern Art (Jama’at Baghdad lil-Fann al-Hadith) in 1951 and the École de Casablanca in Morocco in 1961 – modern art in Lebanon did not emerge from a national dominant trend.

Indeed, some artists federated with each other, as was done in the Association Libanaise des Artistes, Peintres et Sculpteurs (Lebanese Association of Artists, Painters and Sculptors, LAAPS) founded in 1957. However, the local art movements, including orientalism, abstraction, and expressionism, were experimented through separate initiatives by the artists.

Lebanon, between the Western Bloc and the Arab Neighborhood

In the late 1950s, the ideology of Pan-Arabism vividly spread throughout countries including Egypt, Syria, and Iraq. Through many alliances, these latter countries demonstrated a level of hostility towards the Western bloc. For its part, Lebanon adopted a more neutral position, especially under the mandate of President Fouad Chehab (1902-1964), who preferred to temper the relationship with both Arab states and the Western countries. In his vision, Chehab effectively favored discussion with the different political forces – Lebanese and foreign – to preserve national unity. On one hand, he could rely on the support of the United States; on the other hand, he insured the territorial integrity of Lebanon while meeting with Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970) in 1959.

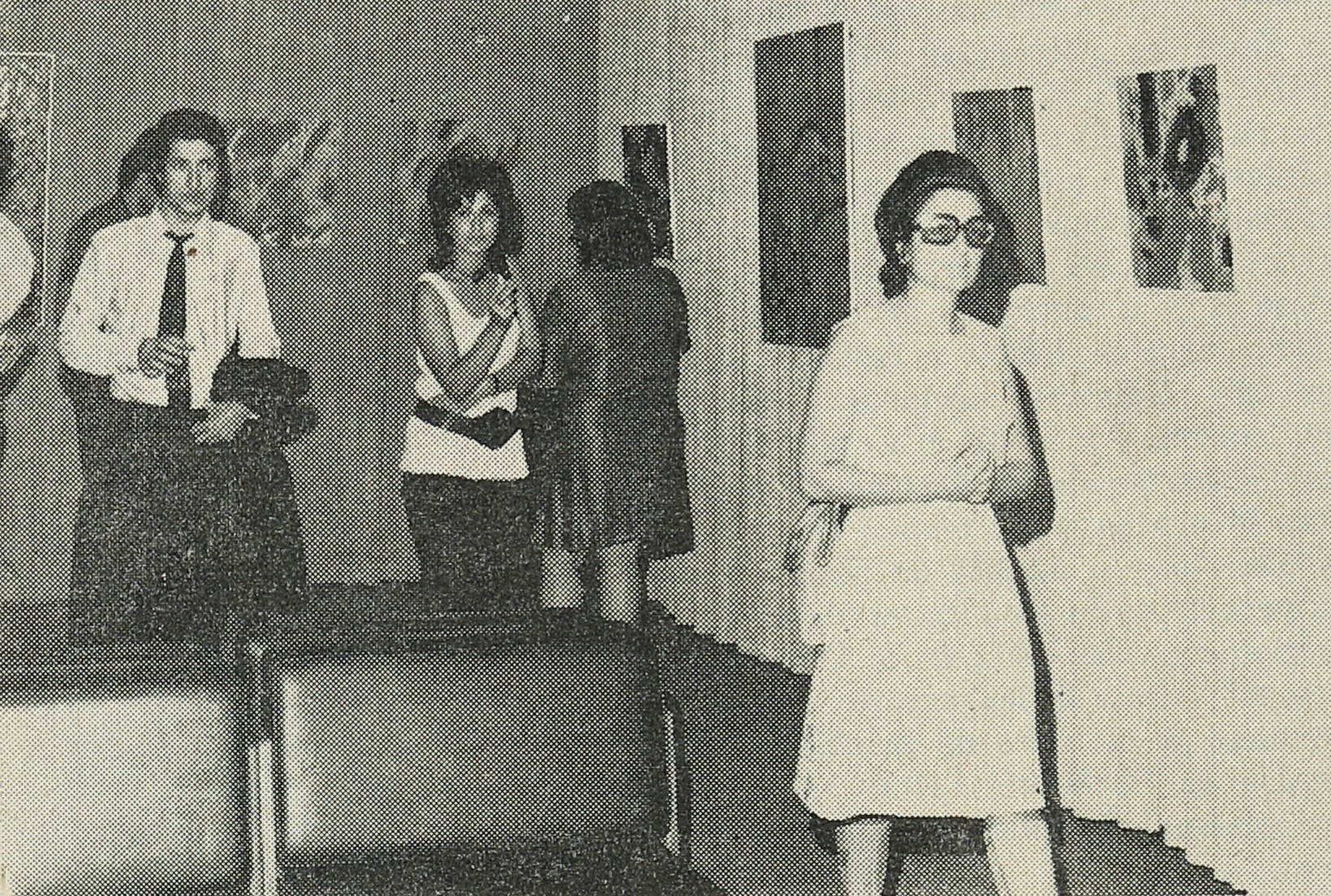

When considering historical context, the question of whether Lebanon were a terrain of soft powers arises. During the Cold War, the efforts by Chehab and his predecessors to keep a neutral policy were observable across the cultural and artistic scenes in Lebanon. For example, as part of the program of the United States Information Services (USIA), the John F. Kennedy American Center opened in Beirut in 1953 8. The center reflected the vibrant and attractive energy of the Lebanese capital city, organizing multiple exhibitions like the solo show for Lebanese artist Jean Khalifé (1925-1978) in 1971 (fig.3).

Figure 3 Opening of the solo exhibition of Jean Khalifé, John F.Kennedy American

Center, Beirut, Lebanon. La Revue du Liban, 25.09.1971. Sursock Museum archives.

Nevertheless, there is no denying that Lebanon was isolated from the Arab neighborhood. During the 1960s, Beirut was actually a major cultural hub in the Arab world. There, ideas about the Palestinian cause, communism, and Arabism were circulated and debated, especially through the publications of new journals like Mawaqif, between 1968 and 1998. Poets, journalists, musicians, and intellectuals such as Syrian Adonis (1930-) and Iraqi Saadi Youssef (1934-2021), formed an important community and stimulated this whole dynamic. Lebanese artist Samir Sayegh (1945-) recounts these times saying: “Beirut was the center of Arab modernity (…). It was also the capital of self-criticism and re-thinking history, religious affiliation, and political rule” 9.

From all the Arab countries, artists like Iraqi Shaker Hassan al-Saïd (1925-2004), Dia al-Azzawi (1939-), Moroccan Mohamed Melehi (1936-2020), and Egyptian Hamed Abdalla (1917-1985) found a place of free expression in Beirut. Sometimes, the city gave more international exposure to some of the newcomers. In 1966 and 1967, the Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock museum held successive exhibitions on Syrian and Iraqi contemporary art. Additionally, Lebanon was one of the first countries to integrate the General Union of Arab Plastic Artists (al-Hay’a li-Ittihad al-Fannanin al-Tashkiliyyin al- ‘Arab) in 1971 with painter Wajih Nahlé (1932-2017) appointed as Public Relations Secretary. As such, Lebanon marked its specificity through its capacity of enriching itself with various cultural contributions.

The Lebanese Abstraction: Eastern or Arab?

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Arabization (al-ta’rib) of the arts and culture reached Lebanon. Once again, the question of affiliation to the Arab identity was posed. In his book entitled Plastic Art in the Arab World (Al-Fann al-Tashikili fi al-Watan al-‘Arabi, 1885-1985) published in 1986, Iraqi critic Shawkat al Ruba’i (1940-) categorically declared that modern Lebanese art was more detached from the search for local heritage (al-turath) which was being highly promoted in some other Arab countries 10. However, this statement should be nuanced as many Lebanese artists worked on Arab-Islamic artistic tradition – namely abstraction – including painters Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017) and Mounir Najem (1933-1989).

Nonetheless, it should be said that the regional phenomenon of Arabization (al-ta’rib) developed in Lebanon, without taking a nationalist direction or aesthetic contrary to neighboring Syria and Iraq. For instance, the modern use of Arab-Islamic calligraphy (hourufiyah) was not connected with the symbolism of a purely Arab art characteristic. Thus, the hourufiyah was not a stylistic and conceptual approach which guided Lebanese artists in their work. To describe the experimentation on abstraction by these artists, the term ‘Eastern’ appears to be more adequate than ‘Arab’. Moreover, there was no intention of showing more legitimacy in the practice of abstraction as Lebanese painter Adel Saghir (1930-) asserted: “We are not trying to compare Western art and Eastern art and determine which is truer. That is not our intention. Likewise, we do not deny the West its own spirituality. Rather we differ in terms of our perspective” 11.

Instead of creating a plastic language focusing on cultural references and responding to the aspiration of a nationalistic program, Lebanese artists like Yvette Achkar (1928-) and Shafic Abboud (1926-2004), conceived the Eastern essence of their identity. They did so by paying more attention to the formal work (choice of colors and technical processes). Since there was no indication of a Lebanese impression, sometimes, the artworks like Suite et Fin (1977) (fig.4) by Abboud, could be visually compared to Western art. Due to the fact that the modern Lebanese movement was integrated in the international grid of avant-garde movements, these artworks effectively offered an international dimension.

Figure 4 Shafic Abboud, Suite et Fin,

1977, oil on paper mounted on wood panel,

70 x 55 cm. The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul

Art Foundation,Beirut, Lebanon.

Anchored at the meeting point between the Western world and a new strengthened Arab pole, Lebanon aimed to sustain harmony in the challenging modern times following its independence in 1943. Without strictly taking any side, the Land of the Cedars adapted itself within the regional and global context. Because it is still in disagreement on the official History of the country, every Lebanese has participated in the elaboration of the national narrative, making the Lebanese identity particular but also complex across the Arab world.

Edited by Elsie Labban

Comments on The Enigma of the Lebanese Individuality