Born in 1925 in Samawah, Shaker Hassan Al Said is an Iraqi artist who remains renowned for his fundamental role in helping Iraq's modern art to take its first step and to develop. In 1948, he...

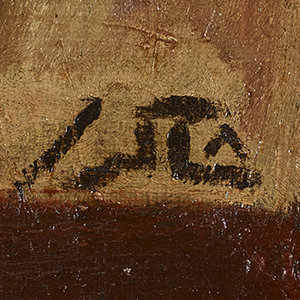

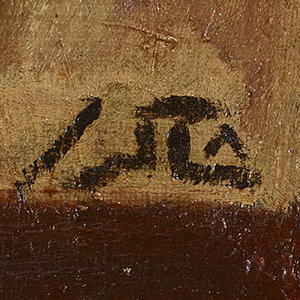

SHAKER HASSAN AL SAID, Iraq (1925 - 2004)

Bio

Written by ARTHUR DEBSI

Born in 1925 in Samawah, Shaker Hassan Al Said is an Iraqi artist who remains renowned for his fundamental role in helping Iraq's modern art to take its first step and to develop. In 1948, he enrolled in Baghdad's Higher Institute of Teachers, where he graduated with a degree in social sciences that he started to teach at Malak Secondary School until 1954. However, he also studied painting and art history at the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad between 1949 and 1954 before completing his education in Paris at the Académie Julian, the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs and the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts under the French painter Raymond Legueult (1898-1971) benefiting from a government scholarship from 1955 to 1959. Upon his return to Bagdad, he held many positions in prestigious institutions starting from 1970 to 1980 when he taught art history at the Institute of Fine Arts before being appointed head of the Department of Aesthetics Studies at the Ministry of Culture and Information from 1980 to 1983. Afterward, he created the symposium of Aesthetic Discourse at the Saddam Art Center in 1994 while being part of the National Committee League of Art Critics, the Iraqi Artists Syndicate, the Society of Iraqi Plastic Artists as well as the Iraqi Teachers' Syndicate. In the Middle-East, he worked as a teacher of painting and art history at the Institute of Art Education in Saudi Arabia from 1968 to 1969. He was a counselor at the Abdul Hameed Shuman Foundation in Amman, Jordan in 1992.

Back to the late 1940s, and while he was still a student, Shaker Hassan Al Said met with Jewad Selim (1919-1961) when the latter was giving a lecture at the Higher Institute of Teachers. Later on, Al Said contributed to the formation of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, of which Jewad Selim was a founding member. proclaimed its manifesto in 1951. The group announced its formation in 1951 through a bold cultural manifesto, declaring its fidelity to the concept of ‘istilham al-turath.’ This phrase, meaning “the inspiration of heritage” in Arabic, was shorthand for the group’s belief that Mesopotamian and Islamic cultural heritage–rather than European fine art– must be the basis for modern art in Iraq. This was only natural, the group argued, because the principles of abstraction, simplicity, and geometry that seemed “new” to Europeans had permeated Arab visual culture since before the arrival of Islam.

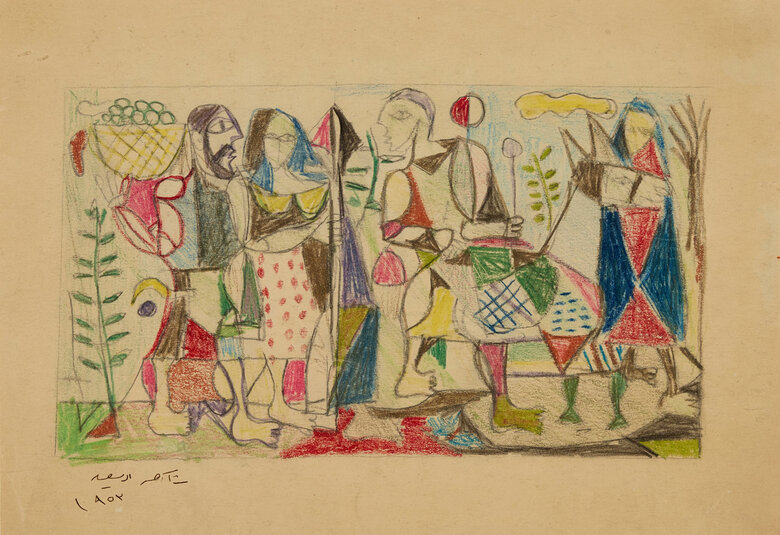

From the 1950s to the mid-1960s, the artistic program of the Baghdad Group heavily informed Al-Said’s early oeuvre, as is seen in an untitled work on paper from 1952, part of DAF collection The pastel drawing depicts an agrarian scene in which four Iraqis, two men and two women, walk alongside one another. One man carries a basket of fruit while the other walks his horse, accompanied by two women –presumably their wives– in traditional clothing, including blue veils that cover their heads. The greenery of the rural environment suggests that the figures are peasants carrying out their daily tasks. The pastel drawing utilizes simple lines, rendering its subjects in simplified geometrical forms with vibrant, pure colors. The work is in keeping with the principles of the Baghdad group in form as well as in content; resolutely modern in appearance, it nevertheless draws from Iraqi source material and subject matter. In arranging the drawing on a frieze, aligning the people with each other in a depthless composition, Al-Said evokes the palace reliefs of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911 to 609 BC). His figures generally reference Sumerian votive statuary, with wide almond-shaped eyes, square shoulders and small, pointed noses. The man on the left, depicted in profile with a beard and a staff, is highly reminiscent of the male archetype in the Assyrian imagery. The horse is also an omnipresent element in ancient Mesopotamian iconography, representing strength and virility as a noble animal that enabled successful military conquests. The artist combines these elements in a nationalistic image of contemporary peasants in order to show his subjects as the direct descendants of these ancient civilizations, “authentic” Iraqis who have perpetuated their ancestral agriculture and local lifestyle through thousands of centuries. The artist was fascinated by the folk culture and legends of Iraq like the tale of Arabian Nights and used to research this theme.

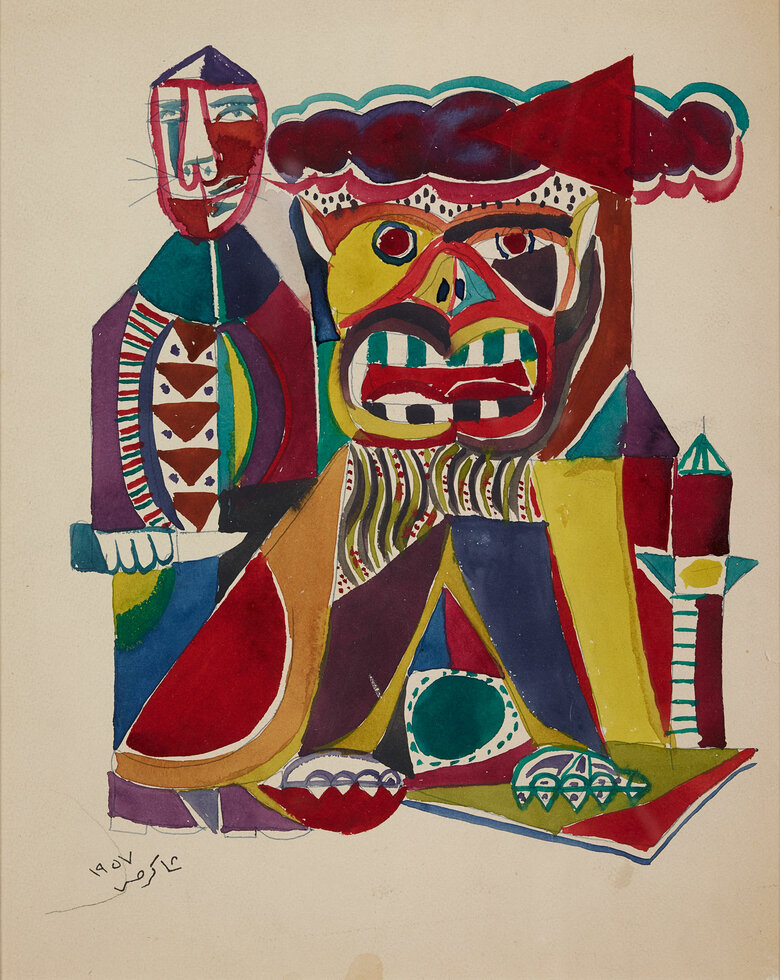

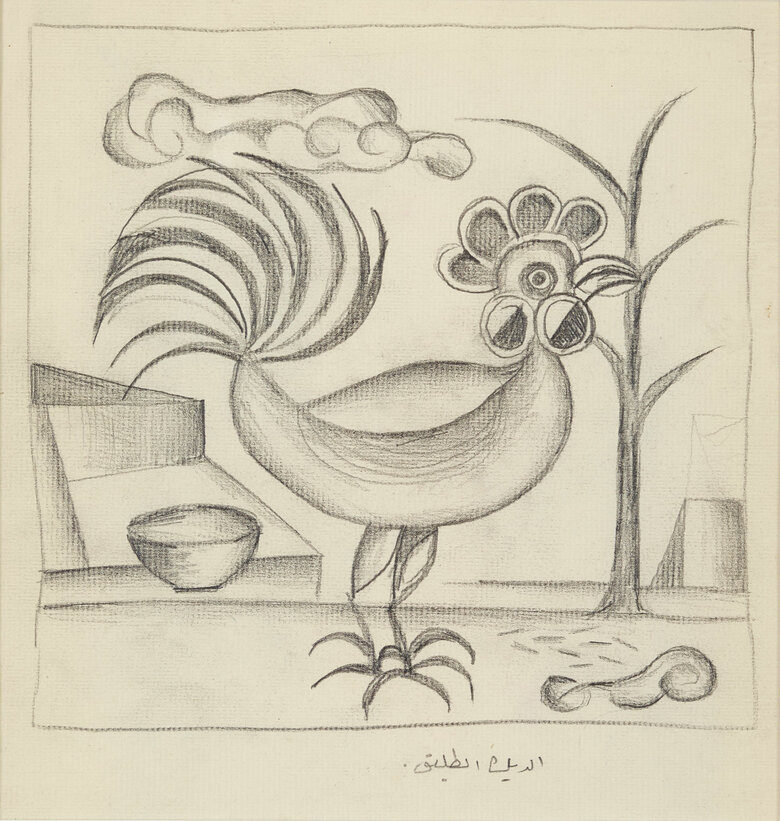

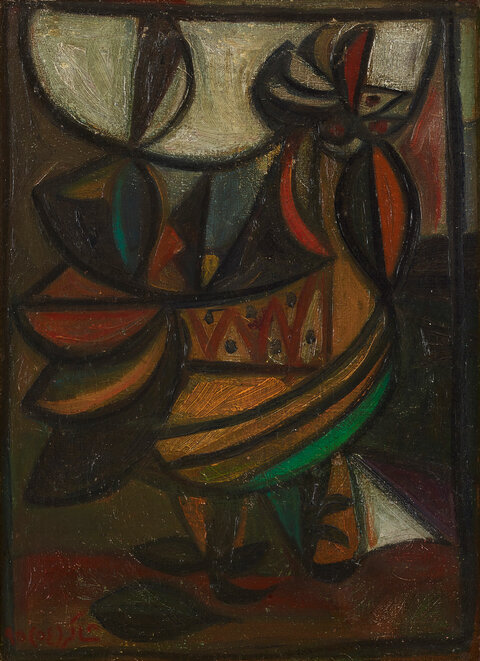

Al Said also drew his inspiration from the Iraqi crafts like pottery, woolen rugs or blankets called Izar known to be made as wedding gifts in the southern regions of Iraq. Since the ancient Mesopotamia, the handmade embroideries show ornamental elements that Shaker Hassan Al Said would incorporate in his subjects through a modern treatment. In his work Cockerel executed in 1954, he painted a rooster that fills up the board from top to bottom. Once again, he employed the shape of crescents and triangles by repetition that he associated with each other to create an enigmatic representation of the gallinacean. The warm color tones of red, yellow, and orange recall the colors of the Izar patterns, and the opposing triangle motif with dots that cover its plumage is also a motif typical of this artisanal production. The rooster is a recurrent subject in the earlier works of the artist, signifying the farm life, sustenance, and the coming of the light. Besides, it symbolizes in Islam the idea of protection as Abu Hurairah (601-676) reported in the hadith collections of Sahih al-Bukhari completed in the 9th century: 'The Prophet said: 'when you hear the crowing of the roosters then ask Allah of his bounty, for verily they have seen an angel.' Through a symbolic painting, Shaker Hassan Al Said linked cultural, religious, and local references creating an artistic identity that the Iraqi public would be able to understand and to appropriate as their own plastic language.

Following the 14 July Revolution of 1958, many political and military actions in Iraq tensed and dragged the country into an unstable situation, starting with the uprising of Mosul – leading to a massacre – in 1959 and the coup of the Baath party in 1963. The painter was personally affected by these events and was subject to profound anxiety to the extent that he was diagnosed with depression. The second phase of Shaker Hassan Al Said corresponded to this phase of isolation when he dived into the tradition of Sufism and philosophical theories from the western culture, such as the existentialist treatises of Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) or Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). In 1966, taking the opposite direction from Jewad Selim, he wrote the Contemplative Manifesto (Al-Bayan Al-Ta'amuli), where he defined contemplative art as a 'testament to the beauty and majesty of the universe.' A spiritual definition deeply marked by Sufi thought and indicating that the work of art aim to attend perfection, an existing truth through which the Creator is exposed.

Shaker Hassan Al Said kept on developing his research until 1971 when he founded the theory of 'One Dimension,' which is a philosophy, technique, and style seeking for eternity, al-azal. Without a beginning or an end, the work of art is infinite and result from human expression. The act of painting itself becomes more central than the subject of a painting as it materializes the choices of the artist. Thus, the artist specifically chose the notion of Hurufiyah in his oeuvre; in other words, the importance of experimenting with the Arabic letter in the search for heritage as a significant art form in the Arab-Islamic civilization. In 1985, he realized The Number 30, which is indicative of his investigations on the letter intended as a form itself and not an alphabetical sign, inviting the viewer to the contemplation. In a free manner, he combined diverse elements, which are letters and numbers, without conveying a proper narrative sense. The Latin letters' A' and 'B' written in blue interact with the number '30' written in Arabic in white, in the middle of the composition. However, he reconnected with the science of al-jafr from the Islamic period when the Sufi mathematician Ahmad al-Buni (died in 1225) indicated: 'Letters express qualities of materials and numbers reveal secrets they contain.' Deeply nurtured by the Islamic thought, he explored the curving and straight lines as an endless series of points, meaning the infinity of the surface, which is a full part of the artwork. Thus, the letters turn into a path which heads the spectators to the Unity and the Infinity of God.

In this painting, the rough appearance of the panel and the earthy tones remind a damaged wall on which he partially applied color gradation as if he barely touched the support and gave a spray paint rendering to the whole by leaving the drippings. This support became a space that Shaker Hassan Al Said exploited for his experimental process directing him to play on the visible and invisible. He consequently established the conception of 'istilham al-sahnah al-jiradiyah' or 'seeking inspiration from or integrating the wall in art.' The wall is the limit between the front and the behind, which is shown by the cracks on it. The painter traced the letters by digging them, and some parts of the painting seemed to be scratched. The cracks emphasize the reliefs and even generate movements from the folds, making the surface living. These characteristics transport the viewer into a mystical journey and a contemplative experience.

The versatile profile of Shaker Hassan Al Said as a painter, teacher, writer, and critic, enriched the elaboration of Modern Iraqi art by proposing intellectual reasoning as well as spiritual. Instead of reinterpreting Islamic aesthetics, he preferred to reinterpret it as a contemporary language and highlighted the philosophical force of the representations. He subverted the traditional vision in order 'to perceive the meaning of art as contemplation, not as creation' as mentioned in his manifesto.

Shaker Hassan Al Said passed away in 2004 in Baghdad.

Sources

Ahmed, Modhir, Charles Pocock, and ʻAzzāwī Diyāʼ. Art in Iraq Today. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2011.

Al-Said, Shakir Hassan. “Aspects of the Modern Arab School of Art” in Gilgamesh: A Journal of Modern Iraqi Artists, n°3, Bagdad, 1989.

Eigner, Saeb. Art of the Middle-East, Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran. London, UK: Merell Publishers Limited, 2011.

Jabrā Jabrā Ibrāhīm. The Grass Roots of Iraqi Art. St. Helier, Jersey, C.I., UK: Wasit Graphic and Publishing Limited, 1983.

Lenssen, Anneka, A. Rogers, Sarah, and Shabout, Nada. Modern Art in the Arab World, Primary Documents. New York, USA: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

Naji, Ahmed. Under the Palm Trees: Modern Iraqi Art with Mohamed Makiya and Jewad Selim. New York, USA: Rizzoli International Publications Inc., 2019.

Pocock, Charles, and M. Shabout, Nada. Modern Iraqi Art: A Collection, [Exhibition catalogue, ‘Modern Iraqi Art: A Collection’, Dubai, Meem Gallery, May 13th 2013 – July 10th 2013]. Dubai, UAE: Meem Gallery, 2013.

Schroth, Mary Angela. Longing for Eternity, On century of Modern and Contemporary Iraqi Art, From the Hussain Ali Harba Family Collection. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2013.

Shabout, Nada. Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida, 2015.

Shabout, Nada. ‘Shaker Hassan Al Said, Time and Space in the Work of the Iraqi Artist: A Journey towards the One-Dimension.’ in Nafas Art Magazine. Accessed January 13, 2020. https://universes.art/en/nafas/articles/2008/shakir-hassan-al-said.

CV

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2020

Shakir Hassan Al Said, Meem Gallery, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

2017

Shakir Hassan Al Said: The Wall, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

2003

Bissan Gallery, Doha, Qatar

Dar al-Anda, Amman, Jordan

Retrospective, Athar Gallery, Baghdad, Iraq

1999

1990s works of art, Athar Gallery, Baghdad, Iraq

1998

Doubles and Allusions, Al Riwaq Art Space, Manama, Bahrain

Doubles and Allusions, Arts Gallery, Tunis, Tunisia

1997

French Cultural Centre, Baghdad, Iraq

1996

Double and One Dimension paintings, French Cultural Centre, Baghdad, Iraq

50x70 Gallery, Beirut, Lebanon

1994

Honorary Exhibition, Saddam Art Center, Baghdad, Iraq

1992

Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, Amman, Jordan

1980

Iraqi Cultural Centre, Beirut, Lebanon

1979

An exhibition with Naja Al-Mahdawi, Iraqi Cultural Centre, Beirut, Lebanon

1978

Sultan Gallery, Kuwait

1974

Reflective Visions, The National Museum of Modern Art, Baghdad, Iraq

1966

Reflections and Ascensions, The National Museum of Modern Art, Baghdad, Iraq

1961

Institute of Fine arts Gallery, Baghdad, Iraq

1954

Institute of Fine Arts Gallery, Baghdad, Iraq

Selected Group Exhibitions

2025

All Manner of Experiments: Legacies of the Baghdad Group for Modern Art, CCS Bard, Annandale-On-Hudson, United States of America

2024

Arab Presences: Modern Art And Decolonisation: Paris 1908-1988, Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France

2023

The Future Of Traditions, Writing Pictures Contemporary Art From The Middle East, The Brunei Gallery, SOAS, Bloomsbury, London, UK

UNTITLED Abstractions, Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

Parallel Histories, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2022

Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s, The Block Museum, Evanston, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Memory Sews Together Events That Hadn’t Previously Met, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2021

Leads & Artistic Cues from the Arab World, Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

2020

Modern Masters, Meem Gallery, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950-1980, Grey Art Museum, New York, USA

2019

A Century in Flux, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2018

Revolution generations, Mathaf, Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

Modern Masters. Iraqi works from the modernist era, Meem Gallery, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

2017

La Biennale di Venezia - Venice Biennale 2017, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy

Modern Art from the Middle East, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, USA

Between Two Rounds of Fire, the Exile of the Sea, Katzen Art Center, American University Museum, United states of America

Chefs-D’œuvre de L’art Moderne et Contemporain Arabe, Institut du monde Arabe, Paris, France

2016

Hurufiyya: Art & Identity, Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Alexandria, Egypt

The Sea Suspended, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran, Iran

The Short Century, Sharjah Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2015

Exhibition 555, Garage Gallery, the Fire Station, Doha, Qatar

2014

Sky Over The East, Emirates Palace, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Tarīqah, Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2013

RE: Orient, Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2012

Caravan, Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2010

Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

2006

Word into Art, Artists of the Modern Middle East, The British Museum, London, The United-Kingdom

2003

The 6th Sharjah Biennial, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

1997

Environment, Surrounding and Ecology in Iraqi Art, Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, Amman, Jordan

1996

The Fifth One Dimension Group exhibition, Abaad Gallery, Amman, Jordan

1994

The Forth One Dimension Group exhibition, Abaad Gallery, Amman, Jordan

1988

Intimacy of Signs, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, France

1986

The 6th New Delhi Triennial, New Delhi, India

1979

The 15th Sao Paulo Biennial, Sao Paulo, Brazil

1977

Arab Art Exhibition, Iraqi Cultural Centre, London, United Kingdom

1976

The 36th Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy

1975

Festival International de la Peinture, Cagnes-sur-Mer, France

1971

Participated in the first and subsequent exhibitions of the One Dimension Group, The National Museum of Modern Art, Baghdad, Iraq

1951

Participated in the first and subsequent exhibitions of the Baghdad Group for Modern Art, Museum of Ancient Costumes, Baghdad, Iraq

Awards and Honours

1986

Saddam Prize for Arts, Baghdad, Iraq

First Prize of the International Festival, Baghdad, Iraq

1981

First Prize of the International Festival, Baghdad, Iraq

1975

National Appreciation Prize, Cagnes-sur-Mer, France

Collections

Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

British Museum, London, United Kingdom

National Museum of Modern Art, Baghdad, Iraq

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

Documents

Shakir Hassan Al Said (1925-2004) Un peintre en quête d’absolu

Mario Choueiry

Centre culturel du livre, French, 2019

Press

Iraqi artist Shakir Hassan Al Said was a genius who taught me how to balance art and life

Myrna ayad

thenationalnews.com, English, 2020

Videos

SHAKER HASSAN AL SAID Artwork

Become a Member

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Welcome to the Dalloul Art Foundation

Thank you for joining our community

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies