Effat Naghi was born in 1905 in Alexandria, Egypt, into a well-connected family. Her father, Musa Naghi Bey, was a landlord who worked as the director of customs in Alexandria, and her maternal...

EFFAT NAGHI, Egypt (1905 - 1994)

Bio

Written by WAFA ROZ

Effat Naghi was born in 1905 in Alexandria, Egypt, into a well-connected family. Her father, Musa Naghi Bey, was a landlord who worked as the director of customs in Alexandria, and her maternal grandfather, Rashid Basha Kamal, was a governor of the Red Sea province. Coming from such a family, Effat had access to elite education for a girl of the time and was home-schooled in music, mathematics, and French literature. As a teenager, Effat often accompanied her father to the village of Abu Hummus, where the Naghi family owned a farm, in order to paint pastoral images of the landscape or portraits of village kids she encountered. The artist was nearly fifteen years old when her brother, the acclaimed painter, lawyer, and diplomat Mohamed Naghi, first recognized her talent for painting. When her elder brother was abroad, the young Effat diligently copied his paintings, both as a way of practicing her skills and of trying to impress Mohamed.

Indeed, Mohamed Naghi’s opinion was always of great importance to Effat. Once, Effat reportedly presented her first painted self-portrait to her exhausted brother, who had just arrived home and disregarded her request for his thoughts. Effat was so angry and disappointed that she destroyed the painting. The next day, Mohamed approached his sister in hopes of seeing the painting, which he remarked had caught his interest, but of course, there was no longer any painting to be seen. Though the young artist felt foolish for having ruined her self-portrait, the incident nonetheless helped her build self-confidence as a painter.

In order to help Effat develop her skills, Mohamed hired an artist –a woman, as was appropriate to the customs of the era– to teach her painting at home. Having begun these lessons as a teenager, Effat found personal and professional success later in life, marrying at the age of 40 and beginning her formal art education two years afterward. In 1945, she married the researcher, writer, and painter Saad Al-Khadem, and from 1947 to 1949, she studied sculpture, fresco painting, and decorative arts at Rome’s Accademia Di Belle Arti. Effat outlived both her husband and her brother, carrying on their artistic legacy and promoting the exhibition of their work.

Effat Naghi’s art shares a conceptual current with the work of the two most important male artists in her life. The first generation of fine artists in modern Egypt, to which Mohamed Naghi belonged, agitated for the revival of Egyptian folkloric heritage in the 1920s, responding largely to nationalistic sentiment surrounding Egyptian independence (1922). In the 1950s, as Egyptians grew increasingly fed up with Britain’s continued involvement in their country’s governance, Saad El Khadem undertook extensive studies of the same subject and wrote about it at length. While Effat Naghi’s work also deals with Egyptian visual heritage, it differs from the oeuvres of Mohamed Naghi and Al-Khadem insofar as it defies the limited modes of academic painting privileged in Egypt during the first half of the 20th century.

The younger Naghi’s deviation from traditional academic painting began in Paris in 1949, when she was introduced to the French cubist painter Andre Lhote. As her instructor for nearly a year, he introduced her to cubism and fauvism, which would ultimately have a significant impact on her stylistic use of color, form, and shape. In 1950, Effat hosted Lhote and his wife in Alexandria. Under the French artist’s guidance, Effat drew the pharaonic tombs they had seen together on their visits to the archaeological sites in Luxor and Aswan. During this period, most of Effat’s work drew inspiration from Egypt and its people, depicting countryside landscapes, peasants harvesting or resting in the fields, and village vendors, such as in The Fruit Seller (1952). Paintings such as The Village present distinctly Egyptian subject matter but also reveal the artist’s fauvist influences. Executed with oil on board, The Village is a landscape structured by long, scattered brushstrokes in hues of turquoise, salmon pink, orange, and pale yellow. Though these colors are bright and artificial, the palette is harmonious and brings the distinct figures of peasants, donkeys, and houses together as if to suggest they are all part of the natural landscape.

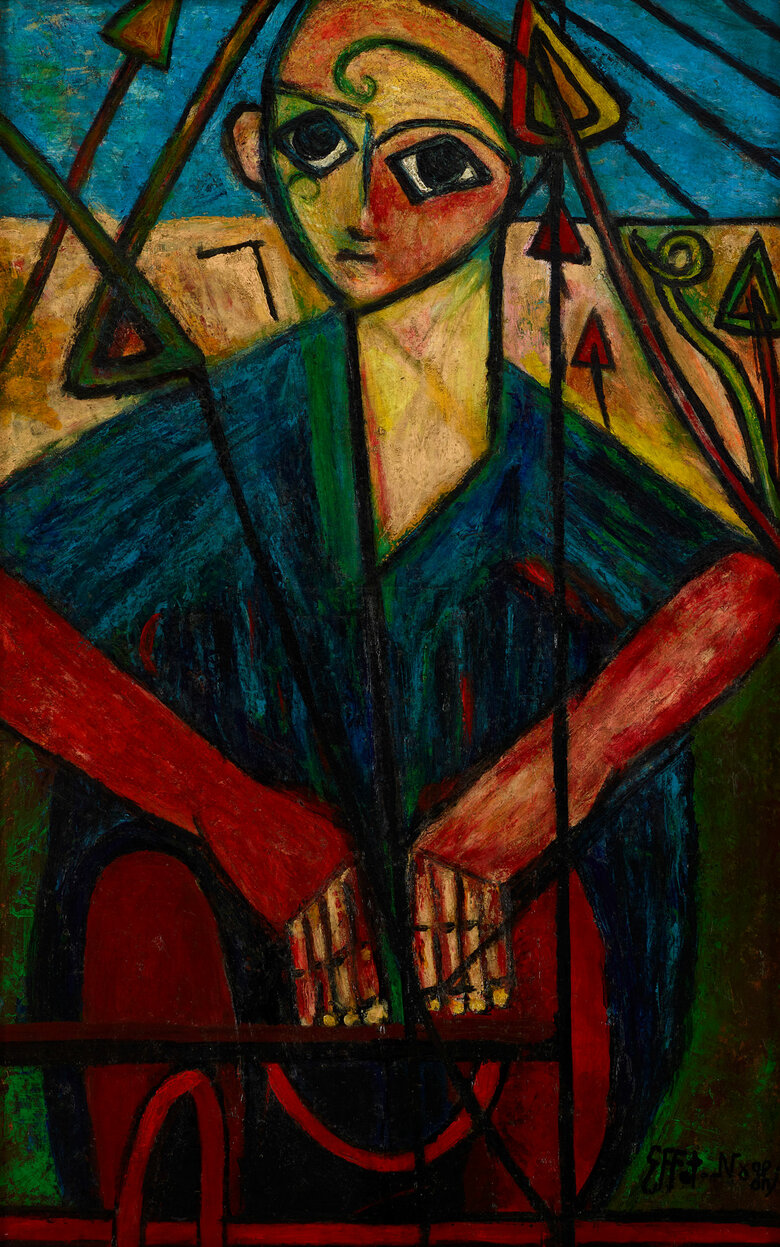

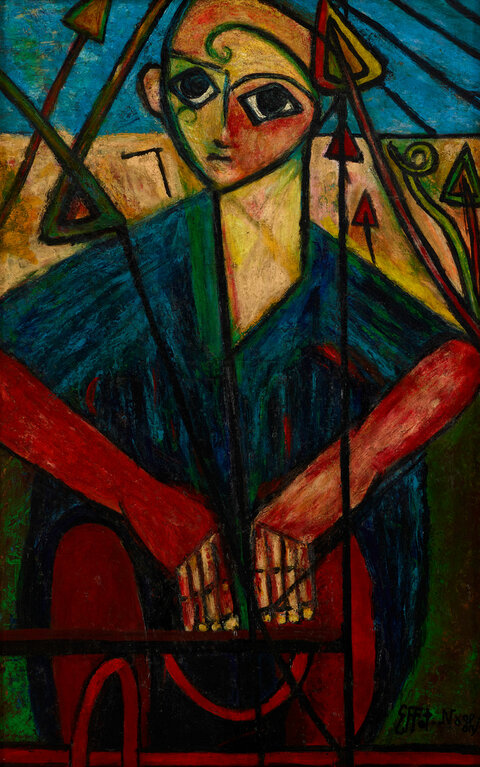

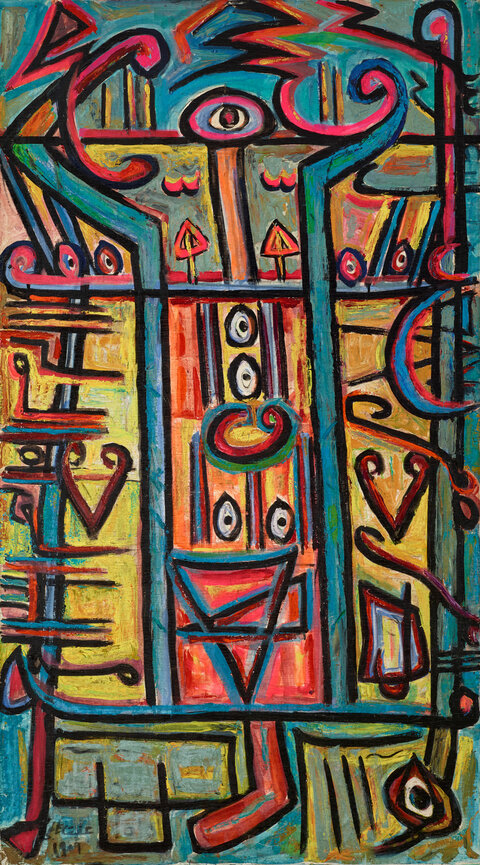

Effat’s work was in conversation with the broader Egyptian art world, which at the time was heavily invested in the links between folklore, ancient Egyptian art, and popular culture. Her husband’s writings, for example, offered a rich background for her visual lexicon, though Effat dedicated a decade of her life to completing her own research. From 1954 to 1964, the artist mined the archives of the Great Cairo Public Library for information on her country’s heritage, delving into ancient Egyptian symbolism and tomb décor, as well as Islamic and Coptic art. For instance, Magic Times (1959) is one in a series of mystic abstract works deploying vibrant colors and emblems marked in bold black lines. The acrylic on board painting includes Arabic calligraphy, linear geometric shapes, arrows, and ten single eyes, evoking mysticism, both ancient and contemporary. In Naghi’s Egypt, the symbol of a human eye evoked the Evil Eye and charms used to protect against it, as it still does throughout the Middle East today. The Eye was also one of the most important symbols of protection, royalty, and health in ancient Egypt, where mummies were usually decorated and imprinted with what was known as the Eye of Horus.

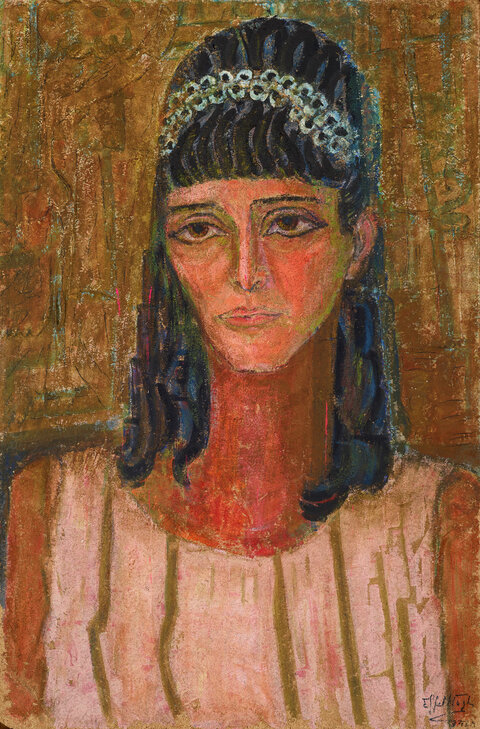

An untitled portrait from 1962 also evokes the art of ancient mummies. Executed with ink and paint on chipboard, the bust portrait shows an aristocratic lady dressed in pink with an ornate band on her hair. The portrait resembles Effat with her slender face, black eyes, long nose, and straight black hair. The work evokes Fayum portraits, a name given to a type of panel portrait originating in the late 1st century BCE or the early 1st century CE in the Fayum basin in Egypt. Created during the Imperial Roman occupation of Egypt, they were done in a naturalistic style heavily influenced by Greco-Roman aesthetic standards and attached to the mummies of the upper class in order to preserve their identities in death.

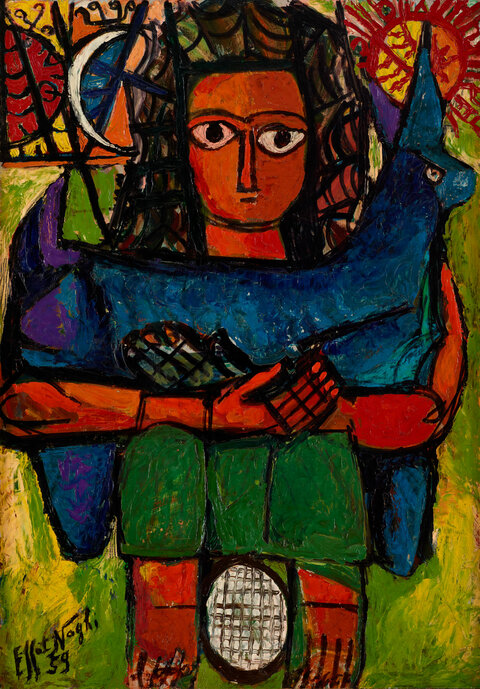

Effat Naghi’s apparent interest in death, mysticism, and spirituality evolved throughout the 1950s, as is seen in The Shepherdess and the Stars (1959). Executed in oil paint on board in simplified forms and artificial colors, the painting features a shepherdess holding a lamb –a symbol of sacrifice in all three Abrahamic religions. In the context of the artist’s oeuvre, the painting could be interpreted as depicting Christian themes; the lamb is a universal symbol for Christ among Christians, and some traditions consider Mary the “Guardian” or “Shepherdess” of the “Divine Shepherd.” The spiritual overtones of the work come through in its animated fauvist style and vivid color palette. The lamb is blue, and its woolen coat conveyed in heavy, textured brushstrokes. Mary’s body and face are contoured in black and saturated with thick layers of red paint, while her outfit is painted in green. Her wide, bright oval eyes transfix the viewer, whose gaze is drawn to her large, black pupils. A crown-like halo surrounds her head, behind which a sun and a crescent shine in opposite corners. In this and many other paintings, Effat abandons the conventional linear perspective of Western academic painting, manipulating elements of color and shape instead to suggest, but not imitate, the effect of depth. The flatness of the figures, as well as the black contouring and large eyes, evoke Egyptian Coptic art.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Effat freed herself from the conventional mediums of most of her contemporaries and produced her most creative and celebrated works. She and her husband were ardent collectors, and she drew inspiration from the items they bought during their travels to Luxor and Sinai. Archaeological relics, Greco-Roman terracotta, Coptic dolls, talismans, traditional Egyptian robes, crocodile leather, and semi-precious stones all found new life as symbolic figurative elements in Effat’s work. She used them to create collages and three-dimensional assemblages in a uniquely intuitive style, influenced by the “primitive” simplicity of ancient art. Placing “Coptic dolls” –small, human-shaped toys or fertility amulets made from bones– into the center of ornately carved wooden backgrounds, Effat transformed centuries-old figurines into modern icons. She was also enthralled by astrology during this period, as is seen in works such as Sagittarius (1961), and Taurus (1972), sometimes incorporating plaster and cutouts of Arabic texts in her abstracted astrological shapes. In Icon of the Nile,1991, the skin of a crocodile cut in the form of an anthropomorphic crocodile once again becomes the Egyptian god of strength and power, Sobek.

In a politically charged Egypt, Naghi’s art was considered inoffensive and meditative. Though she was not involved in any political activism, she was instinctively critical. In 1964, the Ministry of Culture commissioned her, amongst other artists, to reflect on the progress of the Aswan High Dam construction. While some artists addressed the submergence of important archaeological sites, the hazardous labor, and the devastating resettlement of thousands of Egyptian and Nubian peasants, Effat focused on the structural aspect of the project. She created a series of graphic paintings in black and white acrylic on board, including The High Dam (1966), and Les Formes Mécaniques (1966). Her work mimicked technical construction drawings, with densely sketched lines forming an evocative image of scaffoldings, cranes, concrete pillars, and vaults. Effat effaced human presence in her works, and in so doing, accentuated the inhumane aspect of this historical event. She emphasized the destructive nature of an otherwise glorified industrialized project.

Effat was a uniquely creative figure of her time, finding myriad ways to celebrate the richness of Egyptian heritage through art. Following her death in 1994, her house and workshop in the Alexandrian neighborhood of Moharram Bey were tragically demolished. However, as stipulated in her will, The Ministry of Culture converted Effat and Saad El Khadem’s house in Cairo’s Zeytoun district into an art museum dedicated to the couple’s memory.

Sources

Asante, Molefi Kete. Culture and Customs of Egypt. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Dne. “PIONEERS: Saad El-Khadem and Effat Nagy Museum: Recharge Your Inspiration.” Daily News Egypt, 9 Nov. 2012, https://ww.dailynewssegypt.com/2011/01/21/pioneers-saad-el-khadem-and-effat-nagy-museum-recharge-your-inspiration/.

“Effat Naghi.” 1 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy, https://www.artsy.net/artist/effat-naghi.

“Effat Naghi - The High Dam.” Barjeel Art Foundation, 14 July 2018, https://www.barjeelartfoundation.org/collection/effat-naghi-the-high-dam/.

“Effat Nagy and Saad Al-Khadem Museum متحف عفت ناجي و سعد الخادم, 12 شارع الكريم - سراى القبة - الزيتون _ 12, Al-Karim St., Saray Al-Qoubba, Zaytoun District, Cairo., Cairo (2019).” , 12 _ , Al-Karim St., Saray Al-Qoubba, Zaytoun District, Cairo., Cairo (2019), https://www.gluseum.com/EG/Cairo/472040769476043/Effat-Nagy-and-Saad-al-Khadem-Museum-متحف-عفت-ناجي-و-سعد-الخادم.

Introduction to the Coptic Art, http://copticartstudio.com/Intro.htm.

Kane, Patrick M. The Politics of Art in Modern Egypt: Aesthetics, Ideology and Nation-Building. I. B. Tauris, 2013.

Karnouk, Liliane. Modern Egyptian Art: 1910-2003. American University in Cairo Press, 2005.

Metmuseum.org, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/egma/hd_egma.htm.

“Modern Art from the Middle East: Yale University Art Gallery.” Modern Art from the Middle East | Yale University Art Gallery, 24 Feb. 2017, https://artgallery.yale.edu/press-release/modern-art-middle-east.

“My Bonhams.” Bonhams, https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/25686/lot/3/.

Naghi, Effat. “Al Ashkal Al Mechanichiya Bil Sad Al Aali Les Formes Mecaniques by EffatNaghi.” Al Ashkal Al Mechanichiya Bil Sad Al Aali Les Formes Mecaniques by Effat Naghi on Artnet, Quittenbaum Kunstauktionen GmbH, 1 Jan. 1966, http://www.artnet.com/artists/effat-naghi/al-ashkal-al-mechanichiya-bil-sad-al-aali-les-Sx4Dx_fVAtjBkHnpm89lqw2.

Naghi, Effat. “Bayaet Al Fakiha The Fruit Seller by EffatNaghi.” Bayaet Al Fakiha The Fruit Seller by Effat Naghi on Artnet, Christie's South Kensington, 1 Jan. 1970, http://www.artnet.com/artists/effat-naghi/bayaet-al-fakiha-the-fruit-seller-4RT_B5Hx_Vh2VxZgZCHxPA2.

“Primitive Art in Egypt: Capart, Jean, 1877- : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, [Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company] London, H. Grevel & Co., 1 Jan. 1970, https://archive.org/details/primitiveartin00capa.

Qassemi, — Sultan Sooud Al, et al. “The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art.” The Century Foundation, 3 June 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/politics-egyptian-fine-art/.

Radwan, and Nadia. “Between Diana and Isis: Egypt's 'Renaissance' and the Neo-Pharaonic Style (1920s-1930s).” BORIS, InVisu (CNRS-INHA), 1 Jan. 1970, https://boris.unibe.ch/80256/.

Saadedin, Magda, and Gihane Zaki. “Museums and More: Where to Find Egyptian Modern Art.” Rawi Magazine, https://rawi-magazine.com/articles/museums_and_more/.

“Women Artists in Modern Egyptian Art Presented at Green Art Gallery.” Wide walls, https://www.widewalls.ch/female-artists-modern-egyptian-art-green-art-gallery/.

“المؤثرات التى انعكست على الفنانة ..عفت ناجى . فكرياً و فني ., http://redashehata.blogspot.com/2011/03/blog-post_2125.html.

“‘غاليري ضي’... يحتفي بالفنانة الرائدة عفت ناجيأط, https://aawsat.com/print/995041.

A recorded video interview between Effat Naghi and Essmat Dawestashi at DAF.

Art works at DAF.

CV

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2017

Effat Naghi, Dai Gallery, Cairo, Egypt, The exhibition included signing the book ‘Effat Daw’ El Shark’ or ‘Effat, Light of the East’ written about her life by artist and critic Shawky Ezzat

1999

Mashrabia Gallery, Egypt

1992

Fifty Years of Creation by Effat, A-Qandeel Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

1990

Zad Al-Remal Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

1987

Mashrabiah Gallery, Egypt

1981

Al-Horreya Cultural Palace, Alexandria, Egypt

1979

The American Cultural Centre, Cairo, Egypt

1978

Goethe German Institute, Cairo, Egypt

1976

The French Cultural Centre, Alexandria, Egypt

1975

Tiena Gallery, Switzerland

1971

Golden Circle Gallery, Switzerland

1969-

1972

Rome, Italy

1965

Akhenaton Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

1962

Florencia Gallery, Rome, Italy

1961

Art of All Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

1959

Hilton Hotel, Cairo, Egypt

1957

Museum of Fine Arts, Alexandria, Egypt

1956

Association of Fine Arts Lovers, Cairo, Egypt

1953

Alexandria Atelier, Alexandria, Egypt

1952

Alaa Dien gallery, Egypt

1948

Alexandria Atelier, Alexandria, Egypt

Selected Group Exhibitions

2025

Women's Agency in Arab Art: Kinship, Education, and Political Activism, Lebanese American University, Beirut, Lebanon

2024

Arab Presences: Modern Art And Decolonisation: Paris 1908-1988, Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France

The Collector´s Eye XI, Ubuntu Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

2023

Crossroads: A Collector’s Tale, Picasso Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

2021

The Collector’s Eye VIII, Ubuntu Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

Leads & Artistic Cues from the Arab World, Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon

2019

The Collector’s Eye VI, Ubuntu Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

Selection, Zamalek Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt

2017

Modernist Women of Egypt, Green Gallery, Alserkal Avenue, Dubai, UAE

Modern art from the Middle East, Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut, USA

1964

Journey of The High Dam and Nubia, Cairo, Egypt

Modern Art in Egypt, Cairo, Egypt

1959

Landscapes Competition, Cairo Gallery, Egypt

Collections

The Mohamed Naghi Museum, Giza, Egypt

The Effat Naghi and Saad el-Khadem Museum, Zeytoun, Cairo, Egypt

Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

Press

Exhibition Celebrates Egyptian, Iraqi, Lebanese, and Syrian Modern Art.pdf

Masterpieces from Egyptian artists - Daily News Egypt.pdf

EffatNaghi_Al Bawaba News.pdf

أجواء مصرية لتكريم الفنانين عفت ناجي وسعد الخادم في رحاب متحفيهما - بوابة الأسبوع.pdf

Masress _ PIONEERS_ Saad El-Khadem and Effat Nagy Museum_ Recharge your inspiration.pdf

Al Ahram_Article - Zamalek Art Gallery, Contemporary Art in Egypt.pdf

«غاليري ضي»... يحتفي بالفنانة الرائدة عفت ناجي.pdf

Modernist_Women_of_Egypt_Press_Release.pdf

EffatNaghi_LaylalKahira.pdf

Article - Zamalek Art Gallery, Contemporary Art in Egypt.pdf

Al-Ahram Weekly Special Mindful of the masters.pdf

Modernist Women of Egypt — Anna Seaman.pdf

بوابة الأهرام.pdf

مصرس _ الفنانة عفت ناجي وتراثها عند عصمت داوستاشي.pdf

EffatNaghi_Modern Art From The Middle East Cuts Through The Noise_New Haven Independent_Press.pdf

Effat Naghi_BarjeelArtFoundation_Books & Boots_Press.pdf

Women, art and the nation. History of the exhibitions of two Egyptian women artists, from the 1950s to the present day_ Inji Efflatoun and Gazbia Sirry — AWARE Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions.pdf

Renowned Egyptian artists Mohammed and Effat Naghi’s works to be auctioned in Paris.pdf

Modern Art from the Middle East Yale University Art Gallery.pdf

In Chronological Disorder - Mandy Merzaban.pdf

Made_in_the_Arab_World_-_From_Memory_to.pdf

Al-Ahram Weekly Special Mindful of the masters.pdf

Renowned Egyptian artists Mohammed and Effat Naghi’s works to be auctioned in Paris.pdf

7november1956 Guggenheim copy.pdf

PIONEERS_ Saad El-Khadem and Effat Nagy Museum_ Recharge your inspiration - Daily News Egypt.pdf

بورتريه_ عفت ناجي.. الرائدة التشكيلية الموسيقية.pdf

EffatNaghi_Museum_Mobtada.pdf

Women Artists in Modern Egyptian Art Presented at Green Art Gallery Widewalls.pdf

عفت ناجي.. ماذا تعرف عن إحدى رموز مصر في الفن التشكيلي؟ - منصة كلمتنا.pdf

The Activism of Arab Women Artists - CCAS.pdf

متحف عفت ناجى وسعد الخادم.. إيقاع التراث الممتد _ مبتدا.pdf

متحف عفت ناجى وسعد الخادم.. إيقاع التراث الممتد.pdf

1Dreamers and Rebels_ The Artists of the Mid-Twentieth Century Rawi Magazine.pdf

1The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art By Sultan Saoud El qassimi .pdf

1EffatNaghi_The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art_Press.pdf

1r-Dreamers and Rebels_ The Artists of the Mid-Twentieth Century Rawi Magazine.pdf

Art D’Egypte reaches the international arena once again with Effat, Mohamed Naghi’s artworks - EgyptToday.pdf

Egypt’s Artistic Siblings_ Exploring Effat and Mohamed Naghi’s Works _ Egyptian Streets.pdf

EFFAT NAGHI Artwork

Become a Member

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Welcome to the Dalloul Art Foundation

Thank you for joining our community

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies