A significant number of countries constitutive of the Arab world are located in the northern region of Africa, spanning from Morocco to Sudan. These countries have always been the crossroad of both Western and Eastern worlds, where various ancient civilizations developed and merged with one another. Such is the case with Nubia and Egypt. Hence, African countries have consistently maintained close ties with Arab countries especially through commercial exchanges and political alliances. While Pan-Arabism was spreading across the MENA region, Pan-Africanism, a movement developed in the first part of the 20th century, also impacted the political dynamic of some Arab countries like Egypt, Algeria, and Libya.

In the context of the Cold War, these North African countries joined the rest of the African population in their fight against colonialism, serving as a strong support. However, how did this kind of coalition develop? What were the values on which the solidarity between Arabs and Africans based? It goes without saying that African continental cultures have contributed to the elaboration of the Arab culture in North Africa. More than cultural bridges, there was also sometimes the blending of cultures.

Sub-Saharan Africa and its traditions vividly attracted modern Arab artists. Some of them were originally from there. Such artists included Tahia Halim (1919-2003) who was born in Dongola, Sudan, and reconnected with the region and its people she never stopped portraying. This is visible in Three Nubians (non-dated) (fig.1). Yet, it was not just people that were portrayed by the aforementioned artists. Most of the time, the African territories truly fascinated some people who had gone on initiatory trips, like Egyptian painter Mohamed Naghi (1888-1956). He travelled to Abyssinia, formerly Ethiopia, in March 1930, on an artistic mission with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Later on, Moroccan painter Farid Belkahia (1934-2014) travelled to many sub-Saharan countries (Senegal, Niger, Mali) in the 1960s and showed a particular interest in the funeral ceremonies of some tribes1.

Figure 1 Tahia Halim, Three Nubians, non-dated.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

Additionally, to the claimed historical affiliation, the Arab countries considered that African neighboring nations shared the same difficulties and should consequently take the same path. When the Suez Canal Company was nationalized on July 26th 1956, Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970) showed that he was able to defy the Western Bloc. The nationalization effectively took a wider dimension as it somehow symbolized the victory of a country from what was defined back then as the ‘Third World’. Consequently, this encouraged African people to keep fighting against colonial European powers.

The African-Grounded Arabness

Initiated by Ghanaian Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972), the first All-African Peoples Conference (AAPC) took place in Accra, in April 1958. The initial action of AAPC took a step further connecting to the foundation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), in May 1963, in Addis Ababa. Indeed, the right of independence for each African country and the freedom of its populations were the main demands on the table. At that time, the position and the support of the Arab nations in the political environment on the African continent is important to recall. Newly independent Egypt, Sudan, Morocco, Libya, and Tunisia significantly participated in the AAPC. Later on, the following two conferences were held in Tunis in 1960, and Cairo in 1961. The involvement of the Arab nations and leaders for the African cause was such that Algerian President Houari Boumedienne (1932-1978) even served as the first president of OAU.

More than just a demonstration of solidarity, the Arab countries were uniting with their African counterparts around a ‘personnalité africaine distinctive’2, as labeled at the AAPC. This sociocultural specificity then expressed a feeling of belonging to the African identity, of which some Arab populations were convinced. However, this feeling is based not only on the historical-geographic factor, but also on the religious and linguistic ones. As a matter of fact, the number of Muslims was estimated to 242,544,000 people in Sub-Saharan Africa in 20103. Moreover, Arabic is considered the second official language in some countries like Chad and Somalia.

In North Africa, the Arab populations were aware of the contribution of local African cultures to their own. Some people even went as far as to relate to it, such as Moroccan artist Farid Belkahia (1934-2014) did. He stated: “D’abord je suis africain. Je suis de l’Afrique blanche, si l’on peut ainsi diviser l’Afrique, mais tous ceux qui voient mon travail croient que je suis originaire de l’Afrique noire. (…) Je n’oublie pas, en tant que Marocain et Africain, toute la culture des caravanes, tout l’échange intense que le Maroc avait avec l’Afrique” 4. Moreover, celebrating this cultural enrichment consequently sheds light on the specificity of North African cultural identities, as distinct from Middle Eastern cultures for example.

While Iraqi people were reclaiming their Mesopotamian roots, some people were affirming their attachment to African ancestries. This affirmation sometimes coincided with the construction of a national narrative in Arab countries, like Sudan (balad al sudaan, ‘the country of the blacks’). Although the strategy of Arabization and Islamization was intensely conducted after the country’s independence in 1956, the African origins of Sudanese people was always celebrated. Some intellectuals and writers including Ali El-Makk (1937-1992) and Salah Ahmed Ibrahim (1933-1993) highlighted in their works the complex identity crisis present in Sudan. In parallel, artists from the first generation embraced and exploited this complexity, as Ahmed Shibrain (1931-) and Ibrahim El Salahi (1930-) did. Salahi dedicated a significant part of his oeuvre taking inspiration from African arts and aesthetics. The painter worked on the combination of Arab-Islamic traditional practice, such as calligraphy with African masks portrayed in Allah and the Wall of Confrontation (fig.5). Salahi insisted on this rich interbreeding which corresponded to the Sudanese identity.

Figure 2 Ibrahim El Salahi, Allah and the Wall of Confrontation,

1962, oil on enamel on massonite, 46 x 54 cm.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

The Nubian Experience

The approach to African populations and cultures is specific to each Arab country. Located in the shared border between Egypt and Sudan, the region of Nubia would nourish the imagination of many researchers, archeologists, as well as artists for a long time. It was somehow viewed as a lost paradise, an untouched world where time seemed to be suspended (fig.3). The local people were perpetuating their ancestral traditions, without being disturbed by the stirrings of modern development.

.jpg)

Figure 3 Léon & Lévy (active c.1860's-1910), Le temple de Geif

ou Deir et village Nubien, 185-, Ken and Jenny Jacobson

Orientalist Photography Collection,Getty Research Institute.

Author Nadia Radwan reminds that the earliest artistic representations of Nubian people by Egyptian artists reflected a sort of anthropological approach. In fact, these artists followed a colonial point of view nurtured by European Egypt-based artists like Amy Nimr (1898-1974) and Guillaume Laplagne (1870-1927)5. Yet, this approach progressively evolved, and Nubian people stimulated fascination visible in the works of painters from the generation of al-Ruwwad (The Pioneers). In their search for Egyptian authenticity, Ragheb Ayad (1892-1982), Mohamed Naghi (1888-1956) and Mahmoud Said (1897-1964) to name a few, found inspiration in the daily life of Nubian people. The history of Nubia dates back to the earliest times of African civilizations and has consequently always been connected to ancient Egyptian History. Hence, the above-mentioned artists reinforced the connection and perhaps the civilizational continuity linking Egyptian and Nubian people.

Nubia also sparked a vivid interest among Egyptian painters, when the region was going through a critical time in the 1960s. As the construction of the Aswan High Dam began during that year, the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia was founded in coordination with UNESCO, in order to save artefacts and relocate temples6. Egyptian Minister of Culture Tharwat Okasha (1921-2012) organized a visit of 20 artists and architects to Nubia before the High Dam lake started flooding the Nile valley in 1963. This flooding resulted in the displacement of thousands of people. The salvage of the historical heritage was important to the Egyptian minister and the Sudanese government, but artists including Tahia Halim (1919-2003) and Effat Naghi (1905-1994) did not have much interest in the actual antiquities. They showed a bigger interest in visiting the villages that they depicted, as Seif Wanly (1906-1979) had done in Untitled (1950s) (fig.4).

Figure 4 Seif Wanly, Untitled, 1950s, oil on panel, 47.5 x 67.5 cm.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

Africanism: the Arab and African Unity

In the end of the 1950s, the majority of African countries was still under European colonial control, while the newly independent Arab countries were processing the political change in establishing republican regimes. Defending Pan-Arabism, some Arab leaders simultaneously imposed themselves as strong figures of Pan-Africanism. So did first Algerian president Ahmed Ben Bella (1916-2012) and Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970). The Egyptian president declared in his essay Egypt’s Liberation: The Philosophy of the Revolution (Falsafat al-thawra) published in 1954: “Pouvons-nous ignorer la présence d’un continent africain où nous a placé le destin? (…) Il est certain que les Africains continueront de tourner leurs regards vers nous [Égyptiens], qui sommes les sentinelles placées à la porte septentrionale du continent, vers nous qui constituons un lien entre le continent et le monde extérieur"7. Although a concrete intervention of Arab leaders in the African internal policies could not be undertaken – some tensions could even be noted – the two ideologies of Pan-Arabism and Pan-Africanism coincided on certain points, hence forming a new regional political force.

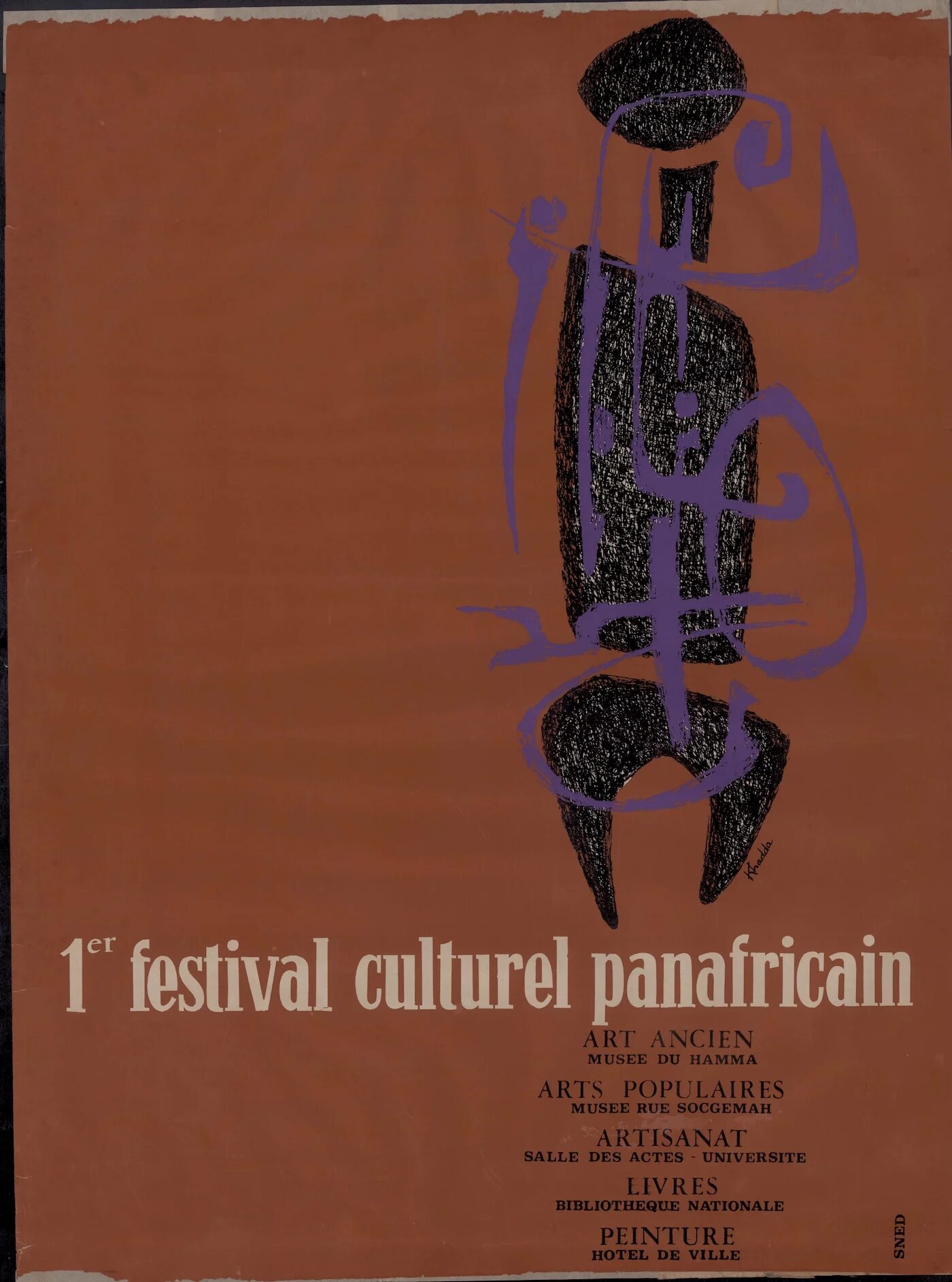

Compared to Pan-Arabism, which is based on ethnic and linguistic affiliation, the ideology of Pan-Africanism was initially conceived through the sense of solidarity among the African peoples, including those from the diaspora8. This unity was visible in the arts and culture, especially during the first edition of the Festival Panafricain (Pan-African Festival) (fig. 5) from July 21st to August 1st 1969 in Algiers. Organized by the Algerian Ministry of Information and the OAU, the festival was aimed to celebrate the greatness of African traditions and culture, gathering artists and intellectuals around the meaning of Africanity.

Figure 5 Mohammed Khadda, Poster for the

1er Festival Culturel Panafricain, Algiers,

1969, 78 x 58 cm.

Furthermore, the event could also be analyzed on a political level. Is not surprising that it took place in Algeria as the country was the symbol of the resistance against imperialism after eight years of war with France. This showed the world the strength of the continent, as Algerian President Houari Boumediene (1932-1978) stated in his speech for the inauguration of the festival: “Il [Festival culturel panafricain] entreprend, par là-même également, une étape nouvelle dans la lutte conséquente contre toute forme de domination”9.

Modernity in the Arab world has particularly been studied within the historical and cultural relationships with the West. These relationships have been the key to understanding the development of political, social, and cultural changes in the MENA region. Nonetheless, the bridges between the Arab and African countries are as equally strong and have even contributed to the regional political strategies in countries like Egypt and Libya. By reinforcing their long-term common history, the African and Arab worlds highlights, again, the complexity to define an identity according to geographic factors.

Edited by Elsie Labban

Comments on Pan-Africanism: Two Worlds, One Continent