Iraqi artist Faisel Laibi Sahi was born in 1947 in the port city of Basra. He was raised in a family devoted to art, so it is little surprise that his eldest brother, Ali, and his younger sister,...

FAISEL LAIBI SAHI, Iraq (1947)

Bio

Written by WAFA ROZ

Iraqi artist Faisel Laibi Sahi was born in 1947 in the port city of Basra. He was raised in a family devoted to art, so it is little surprise that his eldest brother, Ali, and his younger sister, Afifa, both became painters as well. Faisel moved from Basra to Baghdad in 1967 to study at the Institute of Fine Arts, and the capital was a revelation for the young artist. There, he frequented museums, cultural institutions, and national libraries. He studied at the Institute of Fine Arts from 1968-1971, and in 1974, he relocated to Paris. There, Faisel studied painting at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts and art history at the Sorbonne, graduating in 1981. It was also in Paris that Faisel met the love of his life, an Algerian woman named Aisha Khalaf, who later became his wife. In 1984, the couple traveled to Florence, where Faisel was inspired by the Old Masters paintings hanging in storied institutions like the Uffizi Gallery. In 1988, he moved with Aisha to Algeria, where he taught painting and drawing for a short period at the Fine Arts School in Skikda. In 1991, Sahi and his wife moved to London, the city that became their second home.

Sahi’s art is a critical reflection of politics and culture in Iraq. While Faisel matured as a figurative artist outside of Iraq, the Iraqi traditions instilled within him is palpable throughout his oeuvre. His early tutelage was under pioneering modern Iraqi artists such as Faek Hassan, Hafidh El Droubi, and Atta Sabri, and indeed it was Jewad Selim’s philosophy that most impacted Sahi's unique style. Selim advocated the concept of istilham al-turath, or seeking inspiration from heritage; rather than considering modernism an imported, European phenomenon, the philosophy argued for looking at Islamic geometry, Sumerian images, and other elements of Mesopotamian visual culture as sources for abstraction and other forms of artistic innovation. A masterful draughtsman, Sahi amassed an oeuvre of impressive figurative drawings and sensual graphic representations, but his most celebrated works remain the graceful, vibrant paintings that mark the Iraqiness of his culture. Building on the philosophy of Selim and his peers, this work draws inspiration from Mesopotamian mythology, Islamic art, and archaic Arabic literature.

In his early years, Sahi painted realistic portraits of young women, fellow artists, and political figures. He experimented in watercolor on paper and oil on canvas. Sahi also produced some beautiful nudes sketched with charcoal and pastel on paper. In the 90s, he portrayed Arab poets in a fauvist style adopting artificial colors and deconstructed forms. Before he left for Paris, Sahi worked as a journalist and illustrator at the Aleph Baa’ magazine and other Iraqi publications in Baghdad. He was known for his critical writings and daring caricatures, especially in his London based satirical newspaper, Al Mejrasha, published between 1992 and 2002.

Sahi fled Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in 1974 after the authorities took notice of his rebellious stances. Hussein, who ascended to power following the 1968 Ba’athist coup, was only a vice president at the time of the artist’s flight but had become an extremely influential figure as the aging Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr grew increasingly unable to perform his presidential duties. In his work, Sahi condemned the indiscriminate killings of thousands of communists and leftist party rebels that were executed by the National Guard militia under Hussein’s orders. He focused on the torture interrogation chambers of the regime, one of which was located at the former royal palace where King Faisal II was killed. In one of his most poignant paintings, depicting a slaughtered prisoner in Qasr el Akhera, executed in the 1970s with oil on canvas, Sahi shows a prisoner’s corpse lying restless on the floor in a gloomy grey room. In this painting, a spotlight seems to illuminate the blood tarnishing the man’s flesh, evoking European Baroque traditions of dramatic chiaroscuro. The crime scene is announced by the artist as "Qasr El Akhera," “Palace of the End,” or the “Hereafter.”

Sahi’s work enraged Iraqi authorities because, more than anything, it is designed to document history in a way that educates his viewers and agitates for justice. As such, he produced a series of 40 surreal graphic representations, The Face (1989 – 1999), that address suffering, With ink and graphite on paper, Sahi illustrated macabre depictions of contorted human bodies, fraught gestures, shattered heads, and amputated limbs depicting the torture people endured. In these and many other drawings, Sahi reveals his astounding comprehension of human anatomy.

The cyclical nature of history is a central theme in Sahi’s work, which excels in tackling historical themes in a contemporary context. The War (2016) is an outstanding example. This series of large-scale paintings revisit the ancient, consequential Battle of Karbala as a means of reflecting upon contemporary wars, martyrdom, and the eternal quest for liberty. The Battle of Karbala, fought in Iraq in 680CE, was the site of Imam Husayn ibn ‘Ali’s tragic death at the hands of the mercenaries of Yazid bin Mu'awiya. Though the rift between Shi’a and Sunni Muslims had begun to take shape prior to the battle, the events at Karbala solidified the distinction, and today the event holds particular significance for the Shi’a community. Painted in acrylics on an epic scale, The War reflects on this ancient event with relation to the wars fought by Saddam Hussein against Iran and Kuwait, his massacres of Kurds and Shiites, and the US-led invasion of Iraq.

Though the series is based on depictions of Karbala Sahi created in 1986, the artist chose not to reference the battle directly in order to avoid fueling the Sunni–Shiite conflict in Iraq. Instead, he modified the narrative to address Iraqi wars in general. In a horizontal composition, the painting features two larger-than-life white horses on their backs, clearly having yielded to death. From the right, a third horse comes forth with its head raised, ready for attack. In contrast to its white counterparts, this horse is red, the color of blood and fury; it is mournful and seeks revenge. A group of Greek, Roman, Germanic, and Crusader troops approaches from the left, advancing to attack the people of Mesopotamia. Outnumbered and unprepared, the Mesopotamians face a terrible defeat. A decapitated head and several casualties lay still at the lower register of the painting. The warriors in combat carry spears in all intersecting directions and round shields, adding movement and energy to the picture. Sahi also chose to portray his face at the very far right of the painting, eyes watering with tears as he bears witness to the atrocity.

Similarly, the revolutionary artist calls for justice and freedom in his acrylic on canvas painting Uprising (2016). Inspired by the 1991 Kurdish revolt in Iraq, it echoes Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), a famous interpretation of the contemporaneous July Revolution that toppled Charles X’s reign in France. In the older painting, Delacroix personifies the idea of liberty as a woman emerging dramatically from the fray of battle, bare-breasted and proud as she leads the people over a barricade of fallen soldiers. Sahi’s work also features a woman with visible breasts leading her people through battle, moving forward while a crowd of enraged men and women follow. While Liberty holds the French flag in Delacroix’s painting, a nicely dressed young man, possibly an intellectual, holds a red communist flag behind the bare-breasted woman in Sahi's picture. Furthermore, Sahi’s Liberty is preceded by three allegorical animal figures appropriated from ancient mythology and modern Iraqi art: The defiant lioness in ancient Assyrian palace reliefs, the Sumerian sacred bull, and the horse from Baghdad’s Nasb al-Hurriyah, or Freedom Monument, designed by Jewad Selim and completed in 1961.

Like Uprising, most of Sahi’s work negotiates his understanding of istilham al turath. Even those that depart from the nationalistic theme of revolutionary struggle often include visual markers of Iraqi heritage or breathe new life into archaic literature such as folkloric epics and medieval Arabic poetry through a contemporary visual language. His erotic drawings are no exception. These sensual graphics offered imagery to the love and lust voiced by renowned Arab poets such as Umru’el Quays and Ahmad Shawky. Sahi also probed into the wisdom of sexuality in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, depicting the wild creature Enkidu having sex with the sacred prostitute Shamhat; rather than being considered vulgar, this act, in the epic, was essential to saving Enkidu from a life of savagery and taming him for life in human civilization. While Sahi’s mournful women are rendered in simple parabolic forms, veiled in black and maroon, the women he paints in an erotic light are delightfully stylized, mirthfully exposing their nude bodies. Some are more casual and perhaps cheekier than his Gilgamesh depictions: his cautiously-crafted watercolor and ink drawings, for example, feature voluptuous women with long, wavy black hair, reclining on sofas or posing after a bath while a voyeur peeks in the background. Sahi invented a figurative language devoted to replicating the specific beauty of Iraqi femininity.

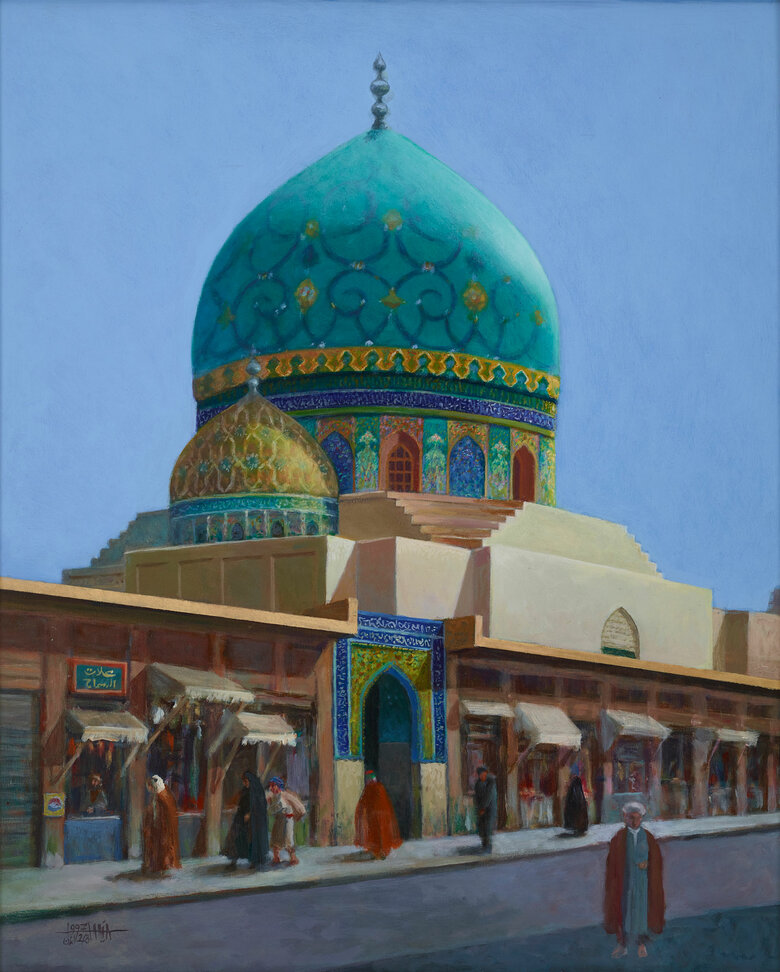

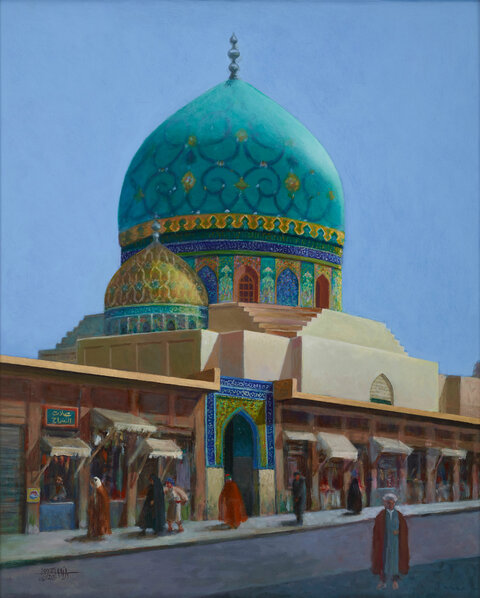

Reflecting on the social life in Iraq, Sahi’s paintings are a combination of reality and fantasy, a waltz between form, aesthetics, and context. Often selecting his subjects from daily life, he produced a collection of charming portrayals in acrylic on canvas that depict recreation and labor. He painted the musician, the tailor, the barber, the fruit seller, and the fisherman. Sahi started his series Baghdad Café in the 80ies and continues to revisit it to date. In the Baghdad Café series, he draws inspiration from Maqamat Al Hariri: a thirteenth-century illustrative manuscript written in Iraq by Al-Hariri of Basra and illustrated by the prominent Baghdadi artist Yahya Bin Mahmud al- Wasiti. Very much like the gracefully adorned Maqamat, the Baghdad Café series presents the café, a communal space, as a platform for social satire. In his latest addition to the series, Baghdad Café (2016), a large- scale painting in acrylic on canvas, Sahi stages key figures that represent different strata of Iraqi society puffing hookahs and chatting together. Religious and military men mingle with the bourgeoisie, the literati, and the working classes, represented by characters like the “shoeshine boy” and the “tea boy.” People engage with various types of print media, some perusing the newspaper while others read The Epic of Gilgamesh or the book of Sahih Al Bukhari, their choice of reading material hinting at both their intellectual prowess and their social pretentions. Sahi's painting evokes Persian or Mughal miniature painting in its absence of the one-point perspective, the unevenness of the three-dimensionality he creates in his figures and furniture. Inspired by Islamic art, Sahi ornaments the lower reflected plane with patterns of colorful geometric tiles.

Each character in Baghdad Café is fashioned in a legible way, with specific costumes and headdresses. Keffiyehs and turbans adorn the heads of religious men, while members of the bourgeoisie each sport a fez, or tarboush, and the sidara designates highly educated individuals or government officials. A lone woman appears in the far right of the horizontal composition, a young child peeking out from behind her chador (a black garment wore by Iranian and Iraqi women). Costume, here, lends social identity and stature to Sahi’s characters, and indeed plays a central part in most of his work.

Even outside of his paintings, clothing has a special place in the artist’s heart. At his wedding, Sahi wore a silky off-white abaya and a sidara – the pointy hat, sometimes known as the Faisalyia after King Faisal I of Iraq. To this day, whenever Sahi feels down, he puts on his wedding costume, symbolic of the Iraqi golden age, to elevate his mood.

Eloquent and moving, Sahi’s paintings are created in an idealized style. They are neat and elegant, with a taste for decorative affluence and vibrant color. His figures are meticulously rendered in subtle, soft effects of paint applied carefully with a thin fine brush, a treatment characteristic of the high renaissance art Sahi admired in Florence. It is worth noting that Sahi adopted an archetypal male figure throughout his oeuvre. This bold male with flawless facial features is reminiscent of Sumerian figurines, or perhaps represents the artist himself as a gatekeeper of history. His work is also known for its emotive use of color; in his tragic works, Sahi’s characters are somberly toned but are brightly fashioned in those with a happier, more lighthearted theme.

An artist with an eye for detail and a talent for balancing whimsy and sobriety, Faisel Laibi Sahi combines the past and present in his compositions with impeccable painterly skill. He and his wife live and work in London to date.

Sources

Laibi Sahi, Faisel, and Haytham Fathallah. Faisel Laibi Sahi Soul Searching. Amman, Jordan: Al-Adib Publishing House,2009.

Daniel, Kavitha S. “Lasting Impression.” Uae – Gulf News, Gulf News, 25 July 2019, https://gulfnews.com/uae/lasting-impression-1.345408.

“Faisal Laibi Sahi. A Century in Flux, Barjeel Art Foundation.” Universes in Universe - Worlds of Art, https://universes.art/en/specials/barjeel-art-foundation/a-century-in-flux/photos/faisal-laibi-sahi.

“Faisal Laibi Sahi. A Century in Flux, Barjeel Art Foundation.” Universes in Universe - Worlds of Art, https://universes.art/en/specials/barjeel-art-foundation/a-century-in-flux/photos/faisal-laibi-sahi.

“Iraq s Past Speaks to the Present.” PDF Free Download, https://docplayer.net/31907916-Iraq-s-past-speaks-to-the-present.html.

Journal, Nazar. “Cultural Continuity in Modern Iraqi Painting between 1950-1980.” Academia.edu - Share Research, https://www.academia.edu/34988694/Cultural_Continuity_in_Modern_Iraqi_Painting_between_1950-1980.

Masarwah, Nader. “The Maqama as a Literary Genre.” Journal of Language and Literature, vol. 5, no. 1, 2014, pp. 28–32., doi:10.7813/jll.2014/5-1/5.

“Modernism and Iraq: Introduction.” Modernism and Iraq | Introduction, http://www.columbia.edu/cu/wallach/exhibitions/Modernism-and-Iraq/introduction.html.

Pakzad, Zahra, and Mahboube Panahi. “Social Criticism in Hariri’s Maqamat with a Focus on Al-Wasiti’s Miniature Paintings.” Asian Social Science, vol. 12, no. 12, 2016, p. 82., doi:10.5539/ass. v12n12p82.

Schroth, Mary Angela. Longing for Eternity: One Century of Modern and Contemporary Iraqi Art from the Hussain Ali Harba Family Collection. Skira, 2013.

Tejel, Jordi, et al. Writing the Modern History of Iraq Historiographical and Political Challenges. World Scientific Publishing, 2015.

"The Recessionistas." Faisel Laibi: The Recessionistas, http://www.therecessionists.co.uk/middle-eastern/faisel-laibi.

YouTube, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KvoA-ks_XOw&feature=emb_logo.

YouTube, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L7AQITjHFcs

YouTube, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQw3KPimPSE

CV

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2023

Faisel Laibi Sahi: I’m Migrant, Bermondsey Project Space, London, United Kingdom

2021

Faisel Laibi Sahi: Iraqi Chronicles: Six Decades of Art, Al markhiya Gallery, The Fire Station, Doha, Qatar

2017

Fantasy of the Forbidden, Art Space Hamra, Beirut, Lebanon

2015

Agony and Recreation, Meem Gallery, Dubai, UAE

2007

Constantine Between Light and Dark, Hall of Constantine city theatre, Constantine, Algeria

Homage to The One Who Gave Me Life and Love, AL Mada 5th Festival, Arbil, Iraq

Memories and Mirrors from Iraq, Old Market Hall, La Rochelle, France

2006

Sadness and Dreams, Gallery Emeraude, Annaba, Algeria

2004

The Baghdad Cafe, Memories of My Youth, Rona Gallery, London, UK

2003

You Are My Country – Iraq, Oriental Art Museum, Oslo, Norway

2002

Forty Years of Painting, Cultural Foundation, Abu Dhabi, UAE

2001

Lovers’ Tales, Notre Alle Gallery, Postdam, Germany, London, UK

1999

Oh My Country Oh Mesopotamia, Sculptures, Kufa Gallery, London, UK

1998

Arabian Nights, Multi Cultures Gallery, Postdam, Germany

1997

Badr Albudoor wa Qamar Al-Zaman (Lovers' Tales), Gallery 47, London, UK

1992

Apocalypse of March, Gallery 4, London, UK

1991

Once Upon a Time (Kan Yama Kan), Kufa Gallery, London, UK

1987

Impressions, Palace of Culture, Annaba, Algeria

1986

Arabesque, Velca Gallery, Rome, Italy

1985

Love and War, Galleria Leonardo da Vinci, Rome, Italy

1984

Forbidden Fruit, Alef Gallery, Milan, Italy

1972

Women and the Poet, inspired by Qifa Nabki poem by Imru’ Al Qais

1966

Studies, Cultural Directorate Gallery, Basra, Iraq

Selected Group Exhibitions

2023

Parallel Histories, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2021

Memory Sews Together Events That Hadn’t Previously Met, Sharjah Art Museum, United Arab Emirates

Leads and Artistic Cues From the Arab World, Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

2018

A Century in Flux: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, UAE

2017

Mathaf Collection, Summary, Part 2, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar

2016

The Short Century, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, UAE

2013

Family Exhibition, Boushahri Gallery, Salmiya, Kuwait

2011

Caravan, Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE

2010

Iraq: Two Faces, Albareh Art Gallery, Adliya, Manama, Bahrain

2009

Modernism and Iraq, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York City, NY

2008

Iraqi Artists in Exile, Station Museum, Houston, TX, USA

2006

Contemporary Arab Representations. The Iraqi Equation, Bildmuseet, Umea Sweden; and Fundacion Antoni Tapies, Barcelona, Spain

2005

Contemporary Arab Representations. The Iraqi Equation, Kunst Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany

Memberships

International Journalists Union

Iraqi Artists Society

Iraqi Journalists Union

French Artist Union

Iraqi Intellectuals League abroad

Iraqi Artists Society in the UK

Collections

Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE

Ibrahimi Iraqi Art Collection, Amman, Baghdad, Paris

Iraq Memory Foundation, Baghdad, Iraq

Louvre Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), Beirut, Lebanon

Press

Lasting impression GulfNews.com.pdf

أعمال الفنان فيصل لعيبي مذاقات لذيذة من الشرق إلى الغرب.pdf

«مقهى بغدادي» في لندن للرسام العراقي فيصل لعيبي,.pdf

Exhibitions - Meem Gallery.pdf

Caravan art exhibition looks back with heart - The National.pdf

Iraqi Association.pdf

فيصل لعيبي يريق دمع الألوان في موكب حزين.pdf

معرض الفنان التشكيلي العراقي فيصل لعيبي.pdf

Al Arab p17.pdf

فيصل لعيبي _ ناظم رمزي .pdf

الواقع بلغة التعبير في أعمال التشكيلي فيصل صاحي صور من الحياة اليومية.pdf

IraqiArt.com - المنتدى العراقي في لندن يستضيف الفنان فيصل لعيبي.pdf

تلك المدينة.. الفيصلية .. إلى أخي فيصل لعيبي صاحي _ جاسم العايف.pdf

Longing To Return_Newsweek.pdf

Faisal LaibiSahi_IraqArtNews_Press.pdf

London art auction showcases diversity of Mideast talent Arab News.pdf

طباعة - فيصل لعيبي_ أرسم محلّيتي.pdf

تشكيليات فيصل لعيبي صاحي_ البحث عن الذات-الأخبار - رابطة المرأة العراقية.pdf

FAISEL LAIBI SAHI Artwork

Become a Member

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies

Welcome to the Dalloul Art Foundation

Thank you for joining our community

If you have entered your email to become a member of the Dalloul Art Foundation, please click the button below to confirm your email and agree to our Terms, Cookie & Privacy policies.

We value your privacy, see how

Become a Member

Get updates from DAF

Follow Artists

Save your favourite Artworks

Share your perspectives on Artworks

Be part of our community

It's Free!

We value your privacy

TermsCookiesPrivacy Policies