During the 1930s, when Iraqi students, like Faik Hassan (1914-1992) and Jewad Selim (1919-1961), were studying art practice in European capital cities, World War II broke out. They had to return to Iraq, where the internal political situation was tumultuous. Being brought into the midst of a world conflict between the Allies and the Axis powers, the Iraqi people aspired for peace, but above all national integrity. In fact, the nationalist movement prominently occupied the political scene in Iraq, especially in the form of fighting against the pro-British Hashemite monarchy.

Modern Iraqi artists witnessed these unstable times, as they went through an experimental stage in the manifestation of their works. They started thinking of an art form which would raise the question of their own identity. In a common effort, they progressively detached themselves from the academic training that they had received in Europe, by adopting innovative aesthetics and techniques. They used them to express what they felt was specific to their historical and cultural affiliation. Like their compatriots – important Iraqi nationalist figures such as General Director for Education Sati’ al-Husri (1881-1968) – these plastic artists certainly felt optimistic that one day they would see the nation of Iraq free and sovereign.

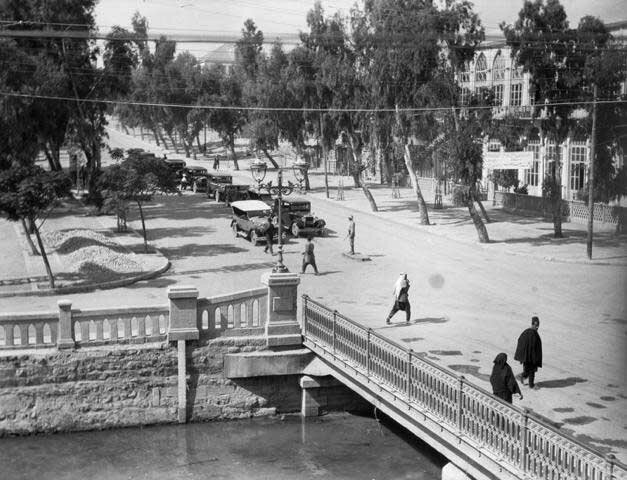

This great hope was born in a context when Iraq had not really belonged to Iraqis. It is worth noting that foreign occupations significantly set the pace of Iraq’s history. The country jumped from the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in 1534, stretching over four centuries, to the British mandate in 1920 (fig.1). Therefore, consideration should be given to how the local history of Iraq could be retraced. More precisely, it is interesting to analyze the time references to which people would reconnect with, while being occupied for so long by others.

Figure 1 Photograph by Kamil Chadirji. 0294ch - Chadirji Foundation Collection,

courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

What is also worth considering is people’s feelings of inferiority nurtured by Western powers. The local population found itself effectively behind in the modernization process. Paradoxically, the Western powers were well aware of the brilliant civilizations born in the Middle East. In Iraq, many archeologists and researchers went on missions to excavate sites, such as Babylon, in 1811-1812. Additionally, English archeologist Gertrude Bell (1868-1926) was appointed honorary Director of Antiquities and helped in building the collection of the Antiquities Museum of Baghdad in 1922. Yet, as is the custom of colonialism, depriving the occupied people of the right to self-determination also meant to disconnect them from their historical background.

The transitional political step in the 1940s and 1950s, leading to the independence of Iraq on July 14, 1958, consisted of the emancipation of people’s minds from an unjustified authority controlling them. For this purpose, it was important for the people to find legitimacy in their fight. Iraqi artists celebrated their glorious past. This legitimacy proved Iraq’s status as an independent nation rather than an inferior one to the West.

Tracing Back History

« Ils [les artistes irakiens] s’aperçoivent que la qualité autochtone recherchée (…) ne pourra s’imposer quand prenant racine dans le sol national »1.

Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, 1962

In 1951, Iraqi artist Jewad Selim (1919-1961) announced in the manifesto of the newly formed Baghdad Group for Modern Art (Jama’at Baghdad li-l-Fann al-Hadith): “In this way, we will honor the stronghold of the Iraqi art of painting that collapsed after the school of Yahya al-Wasiti, the Mesopotamian school of the thirteenth century AD. And in this way, we will reconnect the continuity that has been broken since the fall of Baghdad at the hands of the Mongols”2. Here, Selim mentions a violent event, when the Ilkhanate troops from the Mongol Empire invaded Baghdad in 1258. For many authors, this date marks the beginning of the dark ages, putting an end to centuries of rich artistic production in Iraq3. The country had lost its former glory. To compensate for such frustration, artists like Jewad Selim (1919-1961) and Shaker Hassan al-Said (1925-2004), decided to revive this past production. They travelled back in time and dug into the sources of their history.

Figure 2 Yahya al-Wasiti, 24th assembly illustrated in al-Hariri, Al-Maqama

(The Assemblies),page n°69 (b),1236-1237, 37 x 28 cm. Paris, Bilbliothèque

Nationale de France (Arabe 5847).ã Gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque

Nationale de France. Département des manuscrits.

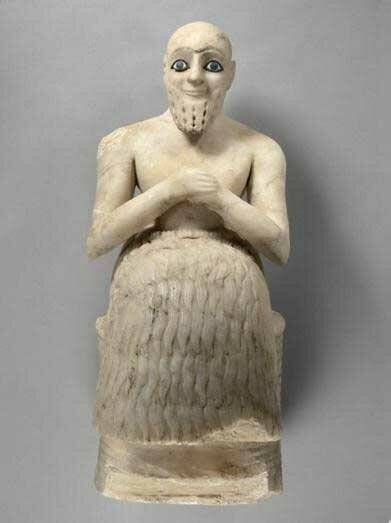

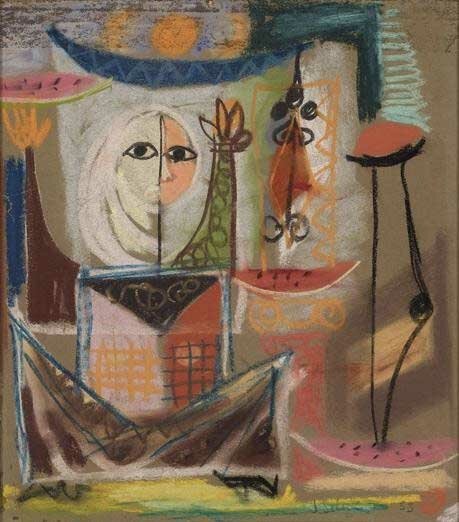

In his oeuvre, Jewad Selim (1919-1961) referred to the work by Yahya al-Wasiti – an Iraqi figurative painter from the 13th century –who illustrated the book written by Iraqi writer al-Hariri, Al-Maqamat (The Assemblies), from 1236-1237 (fig.2). The artist also alluded to the region of Mesopotamia, with which he familiarized himself when he was working as a restorer at the Antiquities Museum of Bagdad in 1940. Being surrounded by Sumerian and Assyrian items – most probably looking like the alabaster statue (fig.3) discovered in 1934 on the border between Syria and Iraq (fig.3) – he declared: “The lines, forms and softly muted colors I use were favored by artists as long ago as 2000 B.C. when the ancient cities of Babylon and the even older Sumer in the Euphrates Valley were the centers of art, learning and fabulous beauty”[4]. Yet, these references were not simply copied in the artworks. They were combined and synthesized, to be adapted to a modern artistic language, as seen in the sketch The Watermelon Seller (1953) (fig.4) by Jewad Selim (1919-1961).

Figure 3 Statue de l’intendant Ebih II, 2500-2340 BC,alabaster,

52.5 x 20.6 x 30 cm. Musée du Louvre,Paris, France.ã 2011

Musée du Louvre / Raphaël Chipault

Figure 4 Jewad Selim, The Watermelon Seller, 1953, pastel on paper,

24.5 x 22.5 cm.The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation,

Beirut, Lebanon.

This retrospective approach is called ‘istilham al-turath’, and commonly translated to ‘seeking inspiration from heritage’. In other words, this is a concept which establishes a cultural, historical, and even spiritual continuity between the present and the past. Specific to the local history and land of Iraq, these sources became a referential point for modern Iraqi artists to trace back to. They would demonstrate to the Iraqis their historical affiliation with the great Islamic and Pre-Islamic civilizations.

Proving Authenticity Against European Supremacy

Displaying the creative potential of the history of art in Iraq, the purpose was to give the country’s historical identity a strong authenticity, ‘asala’. In Arabic, the latter word even derives from the triliteral root ‘asl’, meaning ‘origins’5. This notion sheds light on the considerable importance of Iraqi history, which had nothing to envy from the European powers. The authenticity is unconsciously entrenched in every person, but former Egyptian Minister of Culture Tharwat Okasha (1921-2012) affirmed that it was affected by the spread of the European culture in non-European societies6. The issue has always stemmed from the idea that the European civilization is superior to other civilizations. The European model was synonymous with progress, and modernity. While in contrast, countries like Iraq were supposedly suffering from a ‘déficit civilisationnel’7.

During the initial decades of the 20th century, Iraq was a poor and isolated territory. Great Britain was interested in it only for its strategic geographical location on the route to India. Consequently, through the conceptualization of istilham al-turath, the artists redeemed the reputation of Iraq, by (re)writing history with undeniable actual facts. The region of Mesopotamia, also nicknamed the Fertile Crescent, is historically known to be the cradle of civilization, where the first sedentary societies invented writing, and developed agriculture. Much later, the city of Baghdad became a major place of the Arab-Islamic world, under the caliphate of the Abbasid dynasty (750-1258), where cultural and intellectual activities, as well as scientific progress prospered. The Iraqi artists challenged the Western world’s position, proving the greatness of their rightfully inherited Iraqi civilization.

The ambitious artistic program of the Group of Baghdad for Modern Art (Jama’at Baghdad li-l-Fann al-Hadith), seems to expand beyond simple plastic innovation. Being authentic highlights a specificity: Iraq local history is unique, and could be attributed an equal status with that of the so-called superior European. As Iraqi artist and wife of Jewad Selim (1919-1961), Lorna Selim (1928-2021) declared in an interview conducted by Dr. Ulrike al-Khamis: “He [Jewad Selim] set out to prove that they could be proud of their ancient heritage and did not need to feel inferior to anyone”8.

Considering the Past in a Present Era

Although the process of istilham al-turath could be interpreted by some as an act of romanticizing the past, it was definitely a way to re-appropriate Iraqi local history by artists. In fact, the comprehension of patrimony in Iraq is quite belated. For instance, under the Ottoman Empire, the majority of Islamic structures in Baghdad were disregarded. Iraqi author Kanan Makiya (1949-) even labeled them as “dead sources”9. Moreover, most Iraqi art students in the 1930s did not become aware of the richness of their history until they visited collections of antiques in European museums. Thus, there was a gap to be filled between the people and its history. The artistic revolution initiated by the Group of Baghdad for Modern Art (Jama’at Baghdad li-l-Fann al-Hadith) took on a social perspective. It was necessary to get Iraqis closer to what was left from their past, which had drifted away through the centuries.

Figure 5 Faraj Abbo, Hayder Khana Mosque, 1961, oil on board, 60 x 43 cm.

The Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon.

In their artwork, Iraqi artists subsequently included pictorial elements –sometimes symbolic – that the local audience could easily recognize from daily life. For example, the Hayder Khana mosque in downtown Baghdad, from the 19th century, was recurrently depicted in the works of many Iraqi artists like the duo Jewad Selim (1919-1961) and Lorna Selim (1928-2021), and Faraj Abbo (1921-1984) (fig.5). Though, these motifs were not received with a feeling of nostalgia. They were integrated within contemporary scenes, showing that the past is part of the present, and both could be conciliated.

This visual language was intended for a public expected to be as wide as possible. The mission was fulfilled in 1951, when the Group of Baghdad for Modern Art (Jama’at Baghdad li-l-Fann al-Hadith) held its inaugural exhibition at the Museum of Ancient Costumes in Baghdad, and where “everybody came: teachers, architects, doctors, engineers and diplomats”10. This reveals a willingness of Iraqis to gather around a collective memory, which would be the foundation of their nation. The birth of a nation is effectively built on the sense of belonging, shared by a population with a common history. Hence, it was as if artists restructured a community who would relate to this common history.

The period of the independence movements in the Middle East demonstrated the people’s desire to gain the right of self-determination. Having suffered from permanent humiliation and injustice, these people became increasingly aware of their values and potential to participate in the construction of the modern world in the 20th century. To legitimize their fight, they relied on the strength of their history, helping them build their future. As Jewad Selim (1919-1961) stated: “You have to know where you come from to know where you are going”11.

Edited by Elsie Labban

Comments on (Re)Constructing Iraqi Local History