Last updated on Fri 3 May, 2024

This Exhibition is now closed.

Curated by Wafa Roz

Curatorial Text:

Written by Boushra Batlouni & Sima Ghaddar

Content edit by Wafa Roz

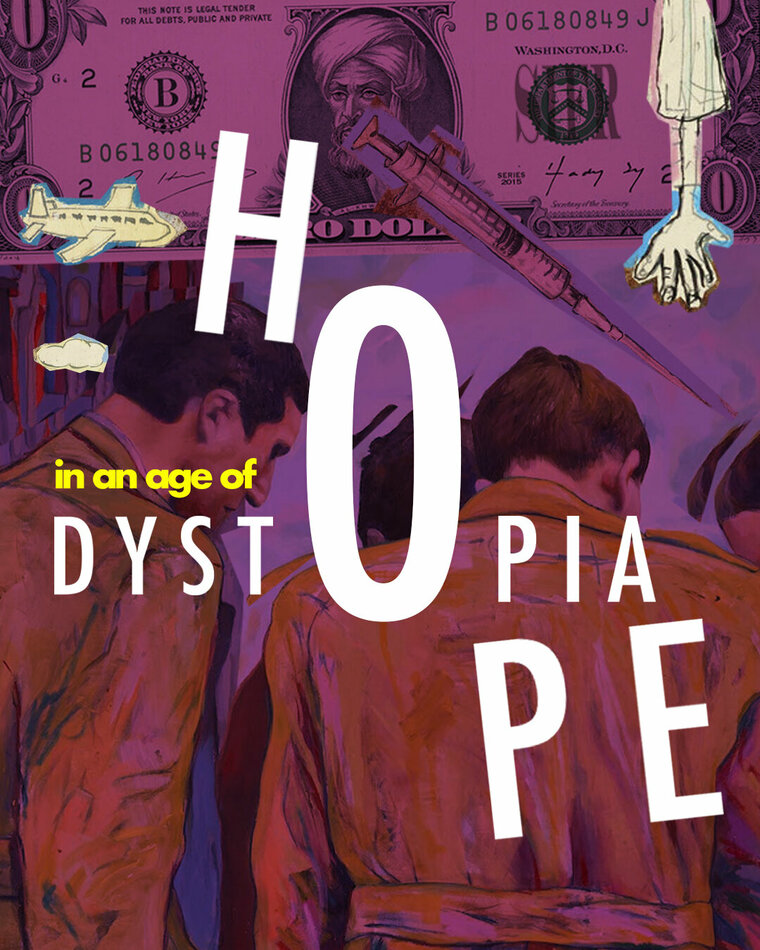

Hope in an Age of Dystopia

General Exhibition Theme

Hope in an Age of Dystopia exhibition presents a selection from the Dalloul Art Foundation’s recent acquisitions. Across this collection, the pieces speak to each other as they tread the fine line between despair and hope. Many of the artworks are vibrant in their form yet often bleak in their content. Some works critique our current social condition with sharp wit, while others playfully invite us to join in on the joke. Yet, they all engage with a dystopian reality characterized by our inability to escape the confines of various systems of control. However, as is common within the dystopian genre, the ultimate motive is not to despair, but to imagine different paths for a better future.

A dystopia is an imagined world, often taking place in the future, where people live in some form of an unjust or oppressive society. In literature, for instance, novels such as George Orwell’s 1984 (published in 1949) and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (published in 1932) present future dystopian worlds that explore the effects of tyrannical governments and technological control, respectively. Most forms of art that deal with dystopian themes are a commentary about a particular moment in history and the collective anxieties and uncertainties it engenders.

This exhibition reflects upon and considers a multitude of domains through which power is exercised today: global capitalist economies and environmental degradation, tech industries and corporate power, laws and regulations, military complexes, and surveillance apparatuses (among many others). Domains of power structure people's daily realities, including their grievances, wants, needs, and feelings. These domains also perpetuate processes of labor exploitation and resource extraction from underdeveloped countries—all in the service of advanced economies, imperialist interests, and global capital accumulation.

Global Political Economy: Late Capitalism & Neoliberalism Shaping Systems of Control

In his 1975 treatise “Late Capitalism,” Marxist economist Ernest Mandel used the term “late capitalism” to describe the economic expansion after the second world war. This was a time characterized by the emergence of multinational corporations, a growth in the global circulation of capital and an increase in corporate profits and the wealth of certain individuals. Generally, late capitalism attempts to explain a new expansionary phase in capitalist development, commonly characterized by a process of capital accumulation, creative destruction[1], and perpetual crisis[2]; as well as by the valorization of capital and privatization, and the expansion of surplus value.[3] Situating the artworks curated for this exhibition within a period of late capitalism provides a useful conceptual framework through which to read our history and our imagined futures. The framework allows us to consider the political, social, and cultural effects of a new expansionary phase in capitalist progression.[4] Many of the art works exhibited explore, critique, and challenge these effects.

As part of late capitalism, the political and economic policies of the 1970s and 80s ushered in what came to be known as the “neoliberal turn.” Globalization, economic deregulation, and the retrenchment of the welfare state, marked the “doctrine of neoliberalism.” Neoliberal discourse held “that the social good will be maximized by maximizing the reach and frequency of market transactions,” and it sought “to bring all human action into the domain of the market.”[5] Though neoliberal rules outwardly reflected free market norms, they functioned primarily to bolster the supremacy of large multinational corporations, advanced economies, and their governing bodies; they perpetuated the interests of the ruling class and exponentially augmented global inequalities.[6] Today, the logic of late capitalism and the discourse of neoliberalism have become deeply embedded in almost all institutions: from universities, think tanks, and corporations, to public institutions, central banks, treasuries, and financial regulators such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB), just to name a few.

Rise of Surveillance Technology & Cultural Logic of late Capitalism

Moreover, in the neoliberal era, governments took a different role in steering the economy and society. On one end, the state was no longer the defender of the rights of citizens, but the defender of the interests of private institutions and powerful individuals. The state rolled back on public welfare programs, leaving “public” welfare in the hands of private institutions. On another end, governments, both authoritarian and democratic, propped up geopolitical power and population control through surveillance technologies. Governmental institutions, alongside tech companies across the world, penetrated the most intimate parts of our lives: our communications, movements, and even our sense of self.

In cultural terms, late capitalism, including the neoliberal turn, explains the emergence of a post-industrial consumerist culture, an information and digital society, and a postmodern aesthetic (like pop art for instance) .[7] In his work, “Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” Fredric Jameson describes the emergence of a “degraded landscape:” a decadent feel , one of aggressive and intrusive advertising, political sloganeering and sound bites, reality TV or low-grade productions etc. Most importantly, Jameson describes a frantic economic urgency to produce ever-newer products, and an unruly desire for us to consume ever-newer goods, and an obsession to look forever young.[8]

Globalization promised a consumerist heaven which will benefit everyone and usher democracy to all the dark corners of the globe. However, it seems to have reneged spectacularly on each of these promises. Today, contemporary systems of control subjugate by manufacturing consent, masking exploitation, normalizing dispossession, stigmatizing, and disciplining the poor, giving the rich, and rewarding artificiality. These dystopian systems of control are not solely confined to the particularities of countries within the Middle East and North Africa but are a culmination of global forces that seem insurmountable.

A Semblance of Hope & An Overview of the Artworks

Still, hope often emerges from the shadows of our dystopian realities. The dreams and hopes of a past era are intricately tied to “the severity of the dystopian projection.”[9] But, in acknowledging the bleakness of dystopia, we may find a fertile ground from which some semblance of hope can flourish, as it is in contrast to despair that hope gains its significance and power. More than a decade has passed since the Arab uprisings, and throughout this period, there have been countless uprisings across the world. With rising global inequalities, cycles of protest and state repression have become all too common. Many of those on the periphery lead precarious lives while raging for hope. Whereas those in the core lead enriched lives while nurturing despair.

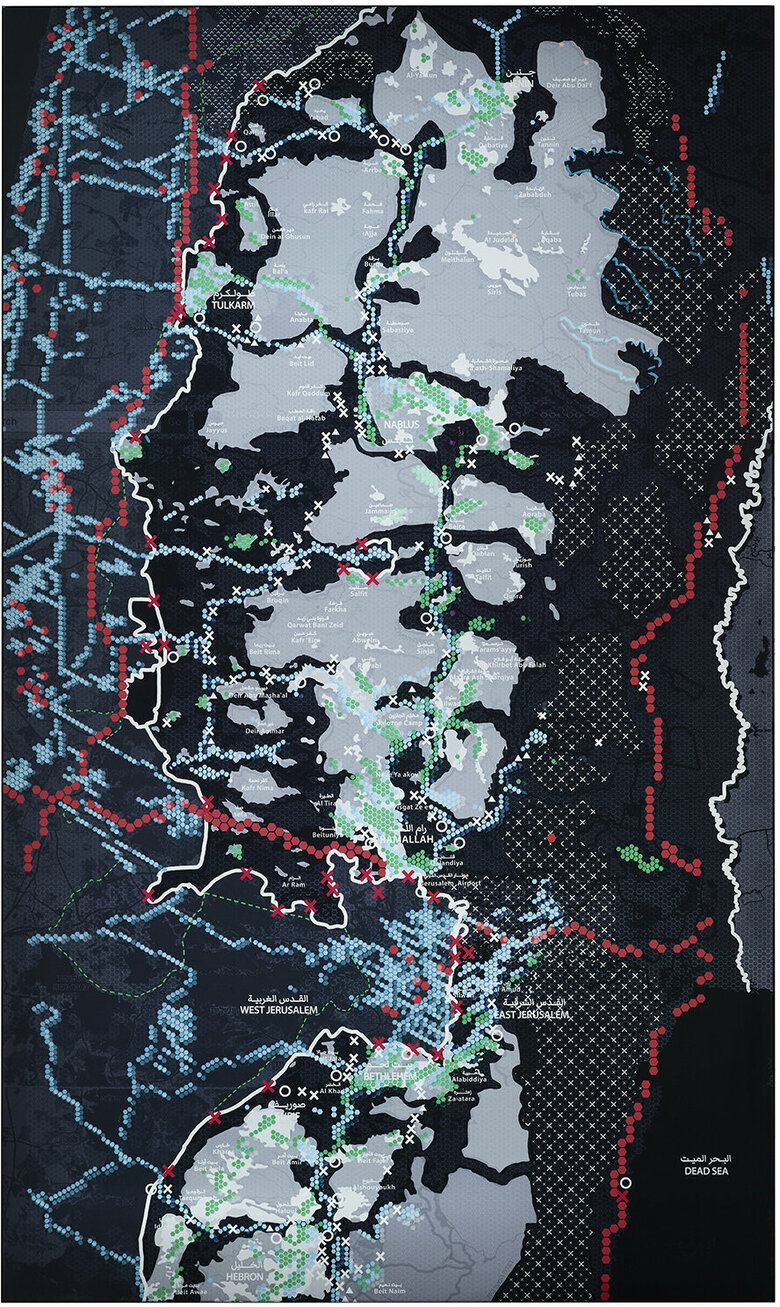

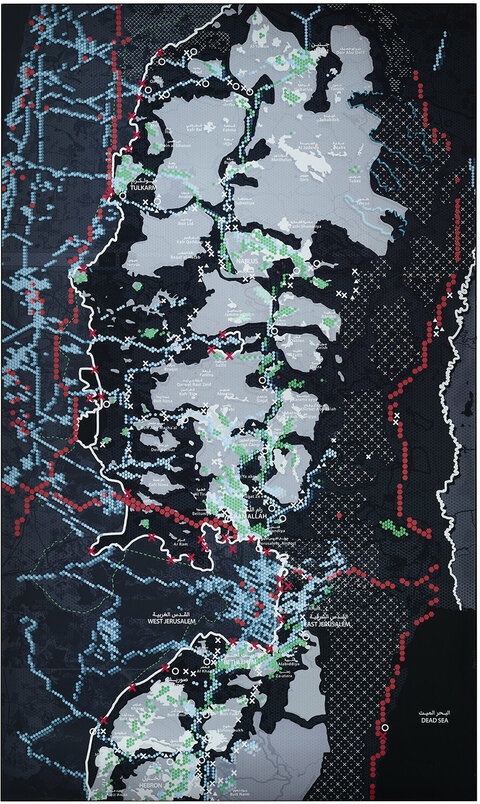

The works within Hope in an Age of Dystopia function across various dimensions of time and space. Many of the works are grounded in the present, forcing us to examine ourselves and our aspirations through them. Works such as Jumanah Abbas’ There’s a Vicious War Launched in the Area of Frequencies, 2023 depict the massive surveillance systems of the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian territories. These systems include cellular tracking frequencies, cameras with advanced facial recognition, and artificial intelligence apparatuses. Abbas’ work brings to the foreground Michel Foucault’s notion of panoptic techniques of dominance. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s architectural prison design, in the panopticon, prison cells are open to a central tower where prisoners can neither see one another nor the prison guards in the tower. But the belief that they are under constant surveillance keeps them disciplined and docile. As such, they internalize the sense of being constantly watched. By mapping the telecommunication structures in the West Bank, Abbas highlights how geopolitical and military power is exerted through surveillance technologies.

Mostapha Akrim’s, Attajamhur, 2022 grapples with the petrification of systems of governance and their attending legislative bodies that never seem to enact the laws they supposedly uphold. His work probes into the idea of citizenship without rights. The layered and deteriorated metal sheets make it difficult to tell the words they represent apart. Instead, they become a single, heavy mass that is eroding. However, in its form, the piece tries to push for a new language that forces us to contend with the principles of freedom of expression, work, and citizenship. Attajamhur, 2022 forces the viewer to take part in attempting to dislodge these principles from their petrification.

Some of the artworks pull upon the threads of what has been forgotten, to be rearranged in the present in the hope they carry through to the future. For instance, Amer Shomali’s piece Broken Weddings,2018 is a conceptual reconstruction of traditional patterns of Palestinian embroidery (tatreez). The patterns are 'conceptually' taken from wedding dresses (thobe) that were left behind during the 1948 Nakba - weddings that never took place..! The artwork is made with new balls of yarn, collected from different villages in Palestine, and stacked next to each other to make up the pattern. Shomali explains that the newness of the spools represents all “the dresses that were not embroidered, broken weddings, unperformed songs, unbuilt homes, unborn children.” The alignment of the spools highlights the vibrancy of the colors used in the dresses, while simultaneously symbolizing a grave yard, reflecting the catastrophe of loss and displacement. The work is a monument to a once forgotten special moment, but it is through the process of remembrance that hope is reignited. It forces its viewer to accept both the survival of the ‘wedding dress’, and its transformation into something else while retaining its essence.

Other pieces in the exhibition weave the past and present of the MENA region into tapestries where intimacy and ruin coexist. Johanne Allard’s three artworks from her series A Feast in the Ruins,2022, function as a “a metaphor for the systematic attacks upon society, cultural fabric and land in the Levant and Arab region through war, dispossession and humanitarian imperialism”[11]. While the embroidery depicts acts of destruction, they are done with such delicacy and intricacy that they demand the viewer come closer to engage with them. It is through this moment of human interconnectedness that such works perform the act of hope: they tell us, inadvertently, that our best chance for the future is through connection, empathy, and the ability to appreciate the importance of intimacy.

Although many of the works reflect themes of dystopia, they do so in conjunction with a sense of diffident hope, one that is burdened with the anxieties of unfulfilled expectations and colonial pasts yet is brash and irreverent in its insistence to manifest despite the overbearing reality. Dystopian narratives, whether referencing oppressive governments, societal control, or apocalyptic destruction, have something in common: regardless of the tropes utilized, they all carry an underlying motif of hope. These stories or representations are never a celebration of destruction and injustice, despite primarily reflecting these aspects. What dystopian narratives do best is bring out the contours of hope, the potential outline of what is wished for through what is presented.

Each of the artworks in this exhibit is an expression of this diffident hope in relation to its context. The mode of expression is predominantly irreverent, often bringing out the absurdity of each issue through a stubborn lack of respect. It is a form of disrespectful mockery, a tongue-in-cheek kind of expression that teeters on the edge of being threatening but holds back just enough to not become lecturing. Irreverence is a profoundly powerful tool that has been utilized in art throughout history. For example, the dadaist movement was a rejection of the values and structures that led to the devastation of World War I. The disillusionment with the upheavals of early 20th century led to the creation of art that was provocative in the questions it raised.

A similar process is happening within this exhibition: the critical irreverence throughout the works here is acerbically intentional in its target, its message, and who or what it deems worthy of respect.

Different Modes of Resistance

Hope in an Age of Dystopia is fundamentally an invitation to imagine a different mode of resistance. It does not ask the viewer to ignore reality, it asks them not to fall into nihilistic despondency. In many of the pieces, this paradox is brought forth through choice of color and material. The bright vibrancy of the works is in communion with the starkness of the content presented. There is a profound sense of vulnerability throughout the artworks and the materials used: delicate and intricate stitching of a harrowing reality, dazzling embroidery of nature overcoming, rusty and repurposed metal molded into expression, bright neon witticisms, and concrete futurisms. All occupy the same space and demand we come to terms with our present reality in order to move past its confines. Yet, every single piece acknowledges a fundamental truth: that intimacy, connection, and communication are the way our hopes can come to fruition.

[1] Creative destruction: is a concept introduced by economist Joseph Schumpeter that refers to the process of innovation and technological change that leads to the destruction of existing economic structures, such as industries, firms, and jobs. This destruction paves the way for new structures to emerge, with the aim of creating long-term economic development. Examples: the internet and the rise of technology is the most obvious of these examples. When this innovation and this change came about, it restructured the whole job markets and systems of surveillance. Or, another example is when in the 1970s the dollar was no longer pegged to the gold, this changed the whole of financial structures etc.).

[2] Perpetual crisis: it is crisis resulting from economic deregulation. Economic deregulation is when the government removes certain regulations when businesses complain about how the regulation impedes their ability to compete. Public authority and money would be used to resolve it, and austerity measures would be demanded as a way to pay for the mistakes. Although deregulation stimulates the economy and reduces bureaucratic hurdles and red tape, deregulation can lead to monopolies, benefit largely corporate actors, and hurt consumers. The financial industry/banks/corporations have become one of the most deregulated industries since the Cold War.

[3] Rowthorn, Bob. "Late capitalism." New Left Review 98 (1976): 59-83; p.62-63

[4] Rowthorn, Bob. "Late capitalism." New Left Review 98 (1976): 59-83; p.62-63

[5] Harvey, David. A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press, USA, 2007. p. 3-4.

[6] P. 57

[7] Jameson, Fredric. "Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism." Postmodernism. Routledge, 2016. 62-92. p. 54; Also see, Bell, Daniel. "The coming of post-industrial society." Social Stratification, Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, Second Edition. Routledge, 2019. 805-817.

[8] Jameson, Fredric. "Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism." Postmodernism. Routledge, 2016. p. 55-57.

[9] Demerjian, Louisa MacKay, ed. The age of dystopia: one genre, our fears and our future. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016. P. 6

[10] https://www.bonhams.com/auction/26663/lot/96/amer-shomali-kuwait-born-1981-broken-weddings-in-salameh/

[11] https://www.johanneallardart.com/work/afeastintheruins-sap9h

Glossary and Primary Terminologies :

Late Capitalism: Largely based on Belgian Marxist economist Ernest Mandel’s treatise “Late Capitalism” published in English in 1975. He used the idea to describe the economic expansion after the second world war. This was a time characterized by the emergence of multinational companies, a growth in the global circulation of capital and an increase in corporate profits and the wealth of certain individuals. The period of late capitalism did not represent a change in the essence of capitalism, only a new epoch marked by expansion and acceleration in production and exchange.

The Dystopian Genre: Dystopian art is a form of speculative fictions and projection in history that imagine a place or vision in the future where societies are in cataclysmic decline, with characters who battle environmental ruin, technological control, and government oppression.

Hope in Dystopia: On one end, art draws us toward apocalypse: it charts unfolding chaos, and the effects of crisis, showing us the dystopian in both our daily life and in our imagined futures. On another end, art’s complexity helps us fathom the uncertainty of the world, question and challenge the order of things, and allows us to imagine new ways of living and being—to make new worlds.

Creative Destruction: Creative destruction is a concept introduced by economist Joseph Schumpeter that refers to the process of innovation and technological change that leads to the destruction of existing economic structures, such as industries, firms, and jobs. This destruction paves the way for new structures to emerge, with the aim of creating long-term economic development (i.e., destroy to recreate)

(yet, many of these recreated structures have worked to sustain and perpetuate global inequalities and accumulation of wealth in the hands of the powerful and the few).

Examples: the internet and the rise of tech. is the most obvious of these examples. When this innovation and this change came about, it restructured the whole job markets and systems of surveillance. Or you can see this in when in the 1970s the dollar was no longer pegged to the gold, this changed the whole of financial structures etc.).

Neoliberalism: In its simplest terms, neoliberalism represents a financial turn in the global political economy. “Neoliberalism stresses the necessity and desirability of transferring economic power and control from governments to private markets, and deregulation, especially in the financial sector and trade markets. Beginning in the 1970s, this perspective dominated monetary policy making in the West, and it spread globally after the Cold” (Centeno, 2012). It represented a dramatic break from the state-managed or state-led development policies of Keynesian economics. In the neoliberal era, governments took a different role in steering the economy and society: the state was no longer the defender of the rights of citizens, but the defender of the interests of private actors and foreign investments. The state also rolled back on its state public welfare programs, leaving “public” welfare in the hand of private companies and private brokers.Culturally, neoliberal economic policies consolidated a consumerist culture where people and their information and desires became the commodity; and where the poor were to blame for their poverty. These policies also equated personal freedom and liberty to free markets, limited government, and deregulation. See a full summary of the “Arc of Neoliberalism” for more.

https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150235

Economic Deregulation: Deregulation refers to “the reduction or elimination of government power in a particular industry.” Economic deregulation is when the government removes certain regulations when businesses complain about how the regulation impedes their ability to compete. Although deregulation stimulates the economy and reduces bureaucratic hurdles and red tape, deregulation can lead to monopolies, benefit largely corporate actors, and hurt consumers. The financial industry/banks/corporations have become one of the most deregulated industries since the Cold War.

Join us in our endless discovery of modern and contemporary Arab art